For international audiences, the Iranian New Wave before the 1979 Islamic Revolution can be more challenging than the universally accessible humanism of Abbas Kiarostami or the moral dramas of Asghar Farhadi. Films from the pre-revolutionary era tend to be more allegorical and deeply rooted in the political and cultural realities of their time. A basic understanding of Iranian society in the 1960s and 1970s can therefore greatly enrich the viewing experience. At the same time, these films function as invaluable historical documents in their own right, offering insight into a pivotal chapter of modern Iranian history.

The cultural climate of the period was shaped by strong anti-imperialist sentiment, rooted in Iran’s traumatic experiences with Tsarist Russia and later the Soviet Union, as well as Great Britain and the United States. Iranian society was deeply shaken by the CIA- and MI6-backed coup (1953) that removed the democratically elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh from power, paving the way for Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s autocratic rule.

One of the most influential texts of the era was Gharbzadegi (Westoxication, 1962), a polemical critique of imperialism by writer and essayist Jalal Al-e Ahmad. He diagnosed Iran as a society afflicted by a “plague of the West”: economically dependent on imports, condemned to imitate foreign culture, and politically subordinate.

Iranian writers and filmmakers of the time were acutely aware of the injustices imposed by foreign powers, yet they did not reject Western artistic forms outright. Instead, they appropriated them to articulate their own concerns—rapid urbanization, social inequality, and the repressive policies of the pro-Western Pahlavi monarchy.

Film critic Farrokh Ghaffari, who would later become one of the pioneering figures of the Iranian New Wave, founded The National Iranian Film Centre (Kanoon-e Melli-ye Film-e Iran) in 1949. The center can be regarded as one of the key forces behind the emergence of the Iranian New Wave. Film and cultural festivals in Shiraz and Tehran also played a crucial role, allowing young filmmakers to encounter international art cinema and engage with the aesthetic currents of global modernism—from Italian Neorealism to the French New Wave.

What follows is my personal selection of ten outstanding movies of the Iranian New Wave made before the 1979 Revolution—works I consider both essential and deeply inspiring. I hope this guide serves as a useful entry point for anyone interested in exploring a lesser-known chapter of film history.

The House Is Black (1963), dir. Forugh Farrokhzad

The nonconformist Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad—celebrated for her sensual and rebellious verse—entered cinema with her only directorial work, The House Is Black (Khaneh siah ast). This twenty-minute movie, made in collaboration with Ebrahim Golestan, is a poetic documentary about people living with leprosy in a colony near Tabriz. Farrokhzad avoids objective observation, blending harsh reality with her deeply personal poetic vision.

Upon its release, the film was praised as a humanist plea for empathy toward the marginalized. In the politically charged climate of the 1970s, however, it was increasingly read as an allegory of Iranian society itself. Critics have often compared it to Luis Buñuel’s Land Without Bread (1933), which similarly depicts poverty and disease in an isolated region—this time in Spain.

Brick and Mirror (1965), dir. Ebrahim Golestan

With his groundbreaking feature debut Brick and Mirror (Khesht va ayeneh), Ebrahim Golestan laid the foundations of the Iranian New Wave. After a nighttime taxi ride with a mysterious woman, Tehran cab driver Hashem discovers an abandoned baby on his back seat. His attempts to get rid of the child lead him into encounters with cold urban bureaucracy and into conflict with his girlfriend Taji, who sees the infant as a moral responsibility.

Golestan uses the architecture of 1960s Tehran not merely as a backdrop but as an expression of the characters’ inner lives and of Iranian society as a whole. Set during the era of the Shah’s so-called White Revolution, the film portrays a city undergoing rapid modernization—yet one in which the human soul finds no place to rest.

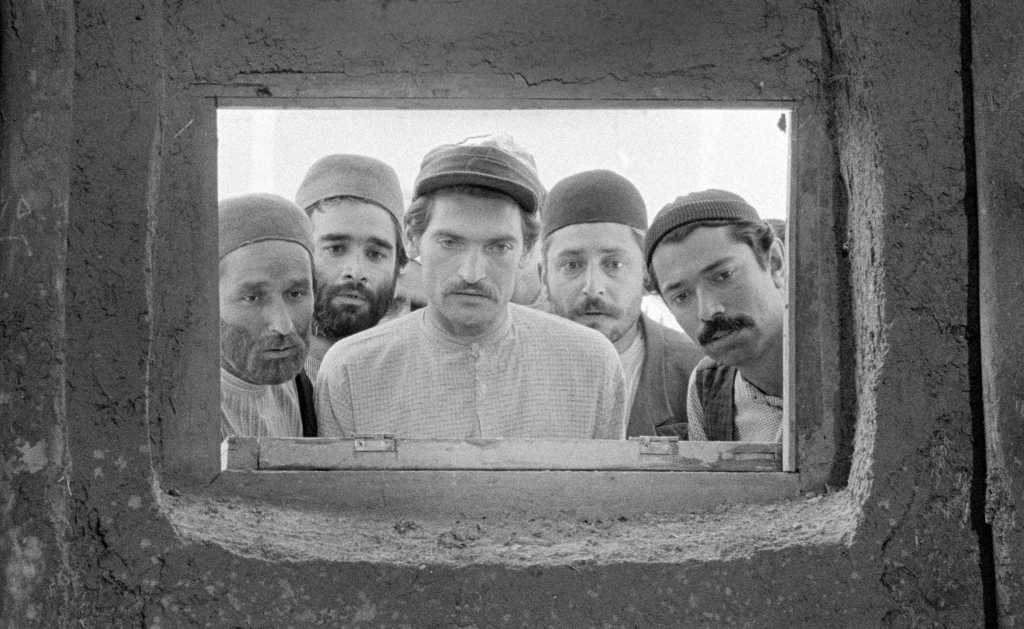

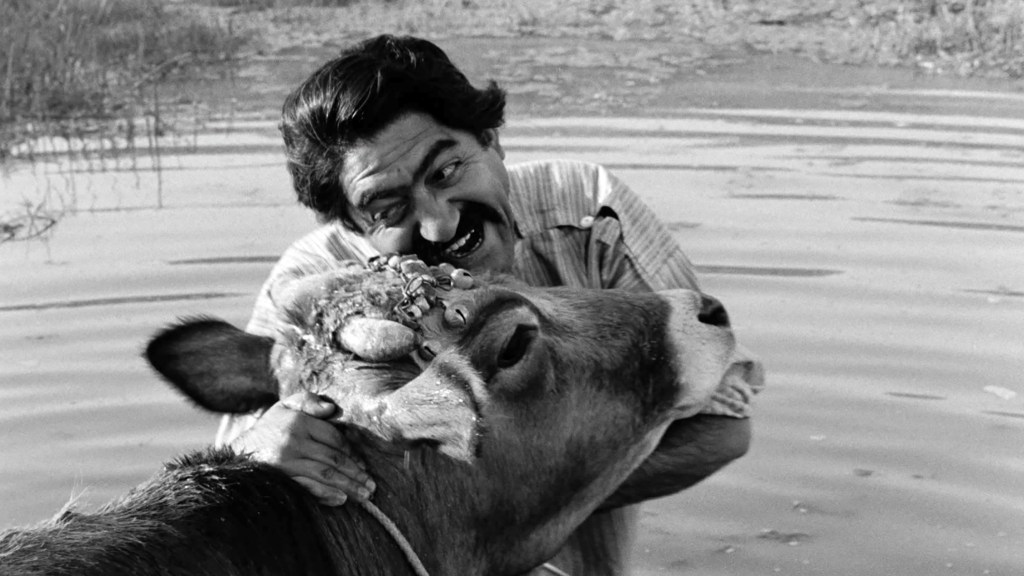

The Cow (1969), dir. Dariush Mehrjui

Widely regarded as the most influential Iranian film of the 1960s, The Cow (Gaav) is a cornerstone of Iranian cinema. Set in a small village, the film follows Masht Hassan, the sole owner of a cow to which he is deeply attached. While he is away, the cow dies, and the villagers—so as not to upset him—tell him it has run away. Unable to cope with the loss, Masht Hassan descends into madness, gradually identifying himself with the animal and moving into the stable.

Based on a short story by Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi from The Mourners of Bayal (1964), the film features a remarkable performance by Ezzatollah Entezami. Though not overtly political, its bleak portrayal of rural life clashed with the Shah’s modernist ideology and led to a temporary ban, lifted only after the film achieved international recognition.

Harmonica (1974), dir. Amir Naderi

Set on Iran’s sun-drenched southern coast, Harmonica (Saaz dahani) tells the story of a boy named Amiro who acquires a harmonica—an object that immediately sparks envy and fascination among the other village children. Amiro soon realizes the power the instrument gives him and begins to humiliate and exploit his friends in exchange for letting them play it.

The harmonica functions as a potent symbol of power, privilege, and capital. Its owner represents an autocrat or ruling elite, while the other children become a submissive mass willing to abase themselves for access. Because the film was produced under the auspices of the Kanoon (Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults) and framed as a children’s film, it may have received less scrutiny from censors.

Still Life (1974), dir. Sohrab Shahid Saless

A must-see for fans of slow cinema, Still Life (Tabi‘at-e bijan) is one of the most distinctive works in Iranian film history. The film portrays an elderly railway gatekeeper and his wife living at an isolated rural crossing. Told in a rigorously minimalist style, it follows the man’s daily routine until the couple is forced to leave their home to make way for a younger employee.

Shahid Saless was a deeply pessimistic filmmaker, known for his austere style, static camera, long takes, and focus on confined spaces. Unlike many of his New Wave contemporaries, he avoided symbolism and surrealism, depicting everyday life with stark detachment. Notably, his radical slowness predates Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), released a year later.

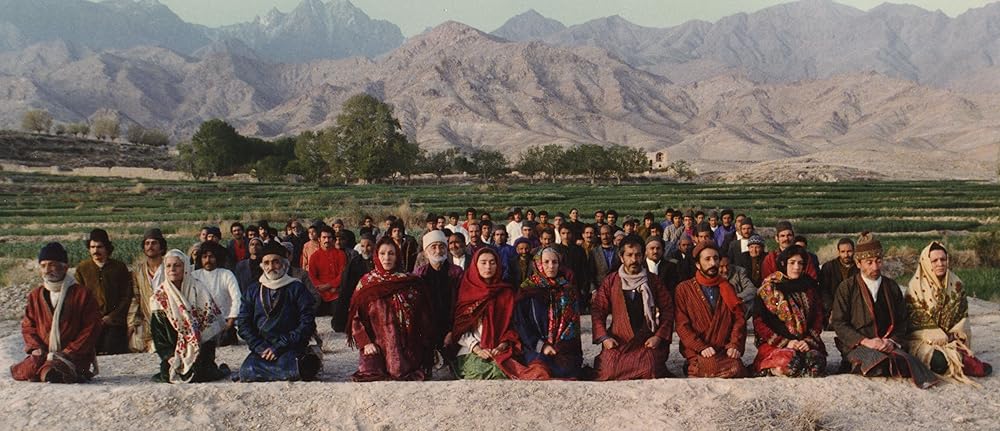

The Stranger and the Fog (1974), dir. Bahram Beyzaie

Recently restored and absolutely essential, The Stranger and the Fog (Gharibeh va meh) marks a shift for Bahram Beyzaie away from the political allegory of Downpour (Ragbar, 1972). Set in a fog-shrouded fictional village on Iran’s northern coast, the story follows Rana, a woman waiting for her husband lost at sea. Instead, a wounded stranger named Ayat emerges from the sea, suffering from amnesia—an event that plunges the village into fear and suspicion.

Beyzaie uses color symbolically to evoke cycles of death and rebirth and incorporates elements of traditional Iranian theater. The film’s timeless setting and ritualistic tone reflect a society shaped by external interference. Often compared to the work of Sergei Parajanov, Ingmar Bergman, and Akira Kurosawa, it is recognized as one of the finest achievements of the pre-revolutionary New Wave.

Chess of the Wind (1976), dir. Mohammad Reza Aslani

Visually mesmerizing, Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-e baad) unfolds in the decadent world of an aristocratic mansion in early 20th-century Tehran, during the final years of the Qajar dynasty. One of the best pre-revolutionary Iranian movies, it depicts a ruthless struggle over a vast inheritance, turning the house into a claustrophobic trap. The film’s meticulous compositions and chiaroscuro lighting evoke painterly tableaux, earning comparisons to Visconti’s The Leopard (1963) and Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975).

Screened only once in Iran at the 1976 Tehran Film Festival, the film vanished due to censorship and survived only in a heavily censored, poor-quality VHS copy. In 2015, the original negative was miraculously discovered in a Tehran antique shop. Restored with support from Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, the film is now available in a stunningly resurrected version.

Dead End (1977), dir. Parviz Sayyad

Dead End (Bonbast) is one of my personal favorites in all of Iranian cinema. It follows a young woman living with her mother on a dead-end street in Tehran, dreaming of love as an escape from daily monotony. She becomes infatuated with a mysterious man who watches her through her bedroom window—unaware of his true identity. His gaze awakens both desire and anxiety, and the film ultimately presents love as a source of existential pain and bitter awakening.

More than a romantic drama, Dead End is a subtle political commentary. The confined spaces create a claustrophobic image of life under the Shah, an era saturated with paranoia. The film is also a striking adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s short story From the Diary of a Young Girl (1883), skillfully relocated to an Iranian setting.

The Sealed Soil (1977), dir. Marva Nabili

The Sealed Soil (Khak-e sar be mohr) is the oldest surviving Iranian feature film directed by a woman. In her debut, Marva Nabili offers a critical alternative to the dominant male perspective of the time. The movie had to be shot clandestinely in a village in southwestern Iran, as the Shah’s regime did not tolerate critical depictions of rural life. It follows Rooy-Bekheir, an eighteen-year-old woman who rejects marriage while her village faces forced relocation as part of a modernization project.

Nabili eschews classical storytelling in favor of a pure slow-cinema approach, reducing the emphasis on dramatic events and focusing instead on time, light, and space. Long takes observe the shifting daylight and the movement of shadows across mud-brick houses. Made during the White Revolution, the film starkly contrasts official modernization rhetoric with the reality of a neglected countryside lacking basic infrastructure.

Tall Shadows of the Wind (1979), dir. Bahman Farmanara

Interested in art-house horror? This one might be for you. In Tall Shadows of the Wind (Sayeha-ye boland-e bad), Bahman Farmanara employs a horror narrative in which a monster disrupts a rural community. The villagers initially pray for a savior and protector, then erect a scarecrow in a field. When a driver draws a face on it, the scarecrow becomes an object of hysteria and obsession.

Adapted from a short story by writer Houshang Golshiri, the film is among the most visually striking works of pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema. Its allegorical nature displeased both regimes: the Shah’s government, when it was produced, and the Islamic Republic, under which it was first publicly screened. Each interpreted the terrorizing scarecrow as a mirror reflecting its own rule.

Which films from my selection of the 10 best pre-revolutionary Iranian movies have you seen? And which ones would you like to see? If you enjoyed this guide to the Iranian New Wave, I’d appreciate your support for my blog on Buy Me a Coffee—and please feel free to share the article.

Leave a reply to Forugh Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black (1963): The Radical Poetry of Ugliness – Iran Zamin Cinema Cancel reply