Beyzaie’s Downpour (Ragbar, 1972) was restored in 2011 as part of the World Cinema Project, an international film preservation initiative founded by Martin Scorsese in 2007 under the umbrella of The Film Foundation. The project seeks out neglected or endangered films from regions that often lack the resources to preserve their own cinematic heritage. Once restored, these films return to circulation through theatrical releases, streaming platforms, and DVD and Blu-ray editions from the Criterion Collection. Other Iranian films restored through the project include The Postman (Postchi, dir. Dariush Mehrjui, 1972), The Stranger and the Fog (Gharibeh va meh, dir. Bahram Beyzaie, 1974), and Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-e baad, dir. Mohammad Reza Aslani, 1976).

The restoration of Downpour was based on a single surviving film positive with English subtitles, provided by Beyzaie himself. As the only known extant copy, it required extensive physical and digital repair, totaling more than 1,500 hours of work. The restoration was carried out by L’Immagine Ritrovata, the laboratory of the Cineteca di Bologna, with financial support from the Doha Film Institute.1 Thanks to this effort, one of the finest Iranian films of the pre-revolutionary era has been preserved for future generations.

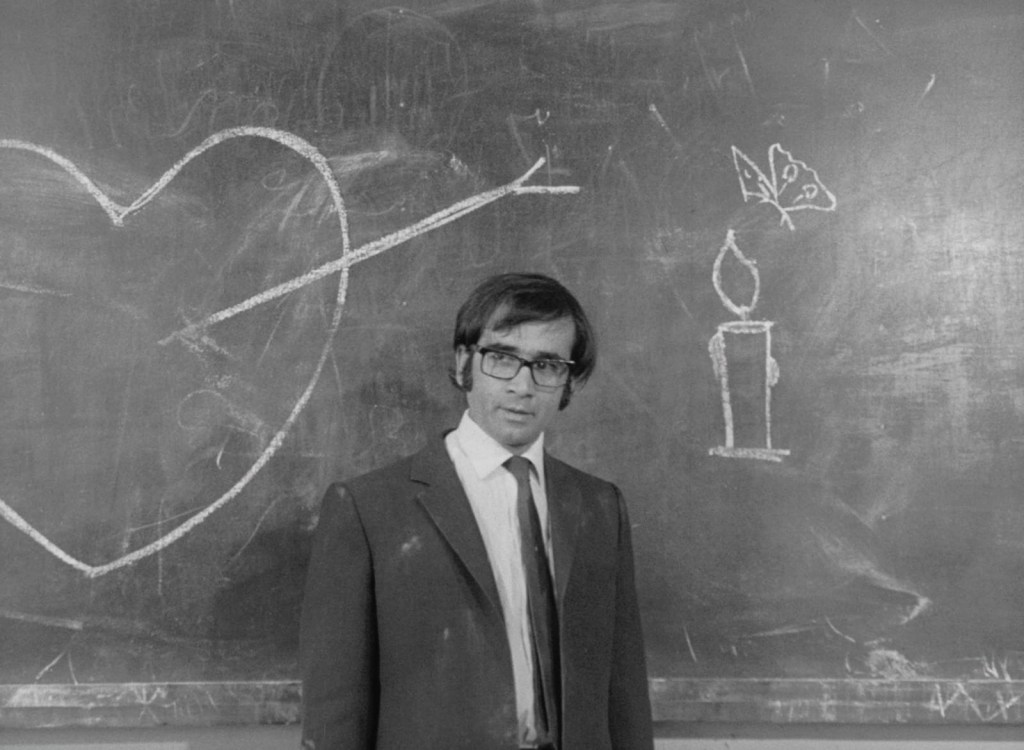

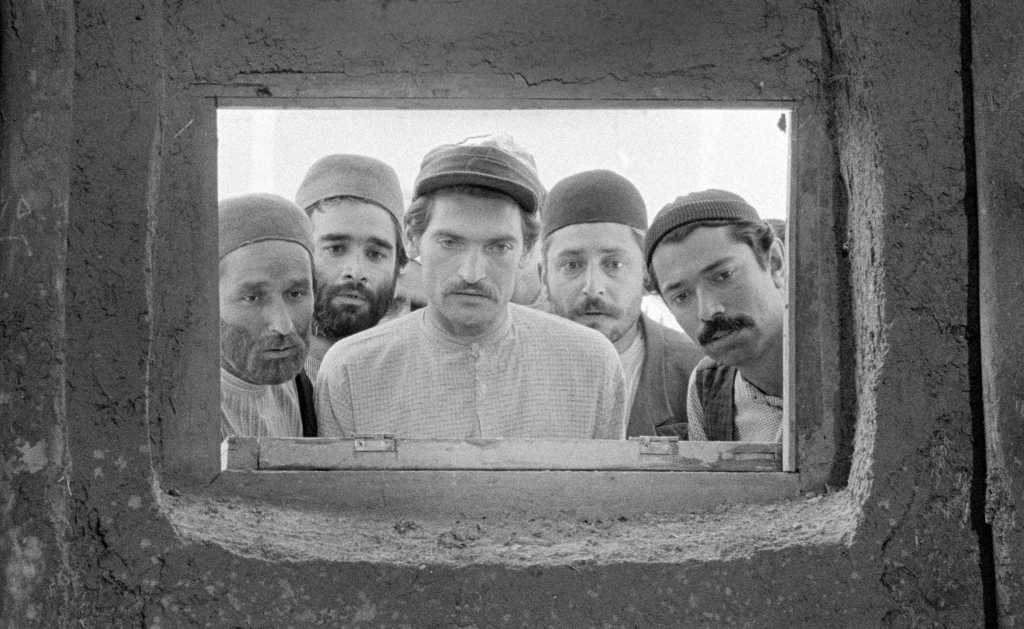

Downpour follows Hekmati (Parviz Fanizadeh), a schoolteacher who arrives—with all his belongings—in a poor neighborhood in southern Tehran. As an outsider entering a tightly knit community, he immediately attracts attention. Atefeh (Parvaneh Massoumi), a young woman, visits him to discuss a disciplinary issue involving her younger brother. Neighborhood children misinterpret their conversation as a romantic encounter and quickly spread the rumor.

A genuine emotional bond does develop between Hekmati and Atefeh, but it is complicated by social gossip and economic pressures. Atefeh works as a dressmaker while caring for her ill mother. She is also under pressure from Rahim (Manouchehr Farid), the local butcher, who wants to marry her and offers financial security for her family.

Political Allegory and the Language of Resistance

Though comedic in tone, Downpour exemplifies the fusion of New Wave aesthetics with political allegory. In certain respects, the film adopts what theorist David Bordwell has described as a historical-materialist mode of narration—an approach rooted in Soviet montage cinema of the 1920s and later embraced by leftist filmmakers in the 1960s and 1970s.2 In this mode, characters function less as psychologically complex individuals and more as representatives of social classes, with narrative emphasis placed on transforming the social order.

The film’s opening scene, in which Hekmati’s cart rolls rapidly down the stairs, is an unmistakable paraphrase of the famous baby carriage sequence from Battleship Potemkin (dir. Sergei Eisenstein, 1925) and can be read as Beyzaie’s explicit homage to Soviet montage cinema.

Downpour was made at a time when education and literacy in Iran were privileges rather than universal rights. In the early 1970s, literacy rates hovered below 37 percent.3 Despite the Shah’s modernization efforts, the divide between urban centers and rural or working-class areas remained stark. Set in southern Tehran, the film shows solitary men wandering the streets at night and women and children working late into the night hours—a quiet but pointed reflection on the failures of Iran’s modernization project.

Hekmati represents the class of Iranian intellectuals (rowshanfekran), a group that in many ways resembled the Russian intelligentsia4 and that stood in opposition to the Shah’s rule throughout the 1960s and 1970s. These intellectuals sought cultural renewal and were deeply critical of Western influence. (Significantly, Hekmati’s name derives from hekmat, meaning “wisdom.”) His efforts to rebuild the school auditorium—where students later stage a play inspired by pre-Islamic Persian mythology—follow a familiar pattern within historical-materialist narratives: the construction of a new social and cultural order.

Hekmati’s primary antagonist is Rahim, the butcher—a symbolic and representative figure embodying power, tyranny, and economic dominance. Rahim presents himself as the school’s patron and as Atefeh’s potential financial provider. The conflict between Hekmati and the community is ideological from the outset and cannot be reduced to romantic rivalry alone. Rather, the film responds to the deep-seated climate of social mistrust that characterized Iran at the time.

Iranian society was dealing with the political influence of the United States and Great Britain. Although Iran was never formally colonized, it functioned economically as a semi-colony of Britain, particularly through oil extraction. In 1953, the CIA and MI6 orchestrated a coup that removed the democratically elected, secular prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. This happened after he had nationalized Iran’s oil industry with broad parliamentary and public support.5

Prior to the coup, Iran was a parliamentary monarchy in which the Shah’s authority was checked by elected institutions. After 1953, that balance collapsed. Backed by Western intervention, Mohammad Reza Shah consolidated power but lacked popular legitimacy, increasingly viewed as an extension of Western imperial interests. Fear permeated society, fueled by the repressive secret police force SAVAK, established with assistance from the CIA and Mossad.6

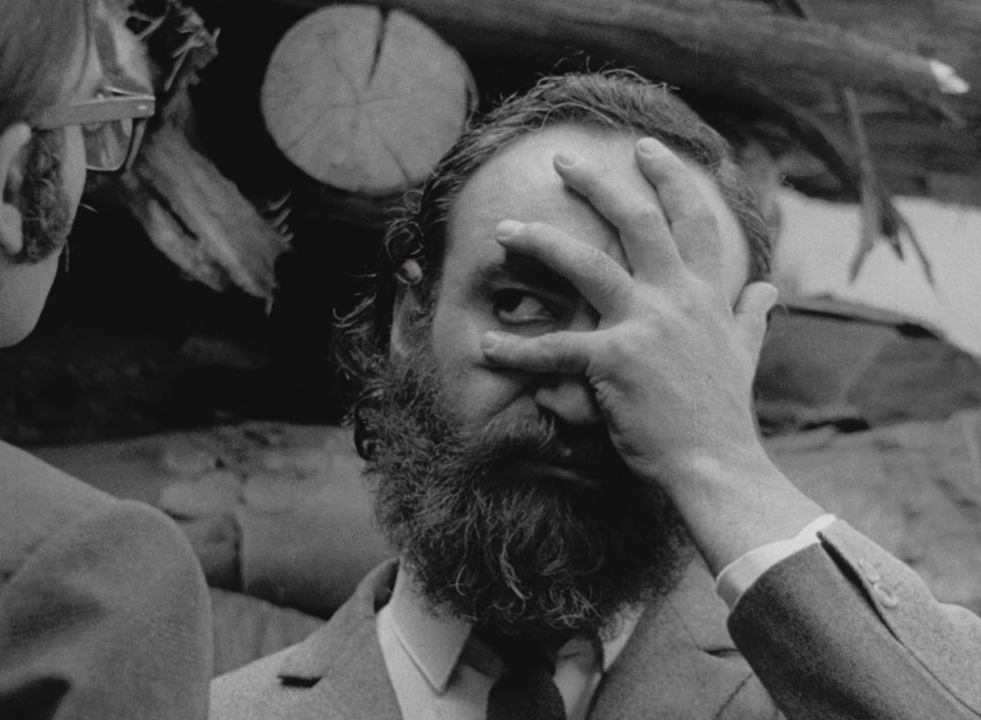

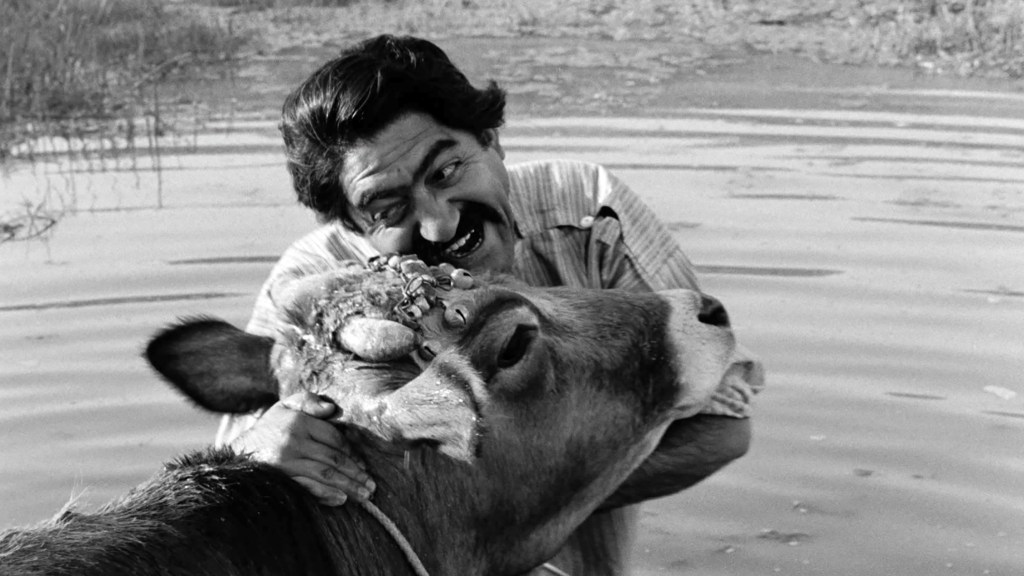

Foreign intervention and state repression fostered a pervasive sense of paranoia, which Downpour translates allegorically into suspicious glances, mocking whispers, and the watchful presence of neighbors and schoolchildren alike. Similar patterns of surveillance and suspicion can also be found in other Iranian New Wave films, such as The Cow (Gaav, dir. Dariush Mehrjui, 1969) and Dead End (Bonbast, dir. Parviz Sayyad, 1977). Film historian Hamid Naficy describes it this way:

“Downpour offers a powerful critique of the secret police without referring to SAVAK directly—a message that, despite the subtlety with which it is delivered, would not have been lost on contemporary audiences. Many viewers would have read the film as Beyzaie’s defiant act of looking askance and sneering at a government that would have failed to read the film with its grain, thus missing its criticism.”7

Beyzaie reinforces this allegorical dimension through stylistic choices. At times, he employs techniques associated with experimental nonfiction cinema, whose meaning is deliberately opaque. Elsewhere, style becomes a tool of social critique. In one scene, as Hekmati lectures his class, his voice is drowned out by music. The gag is comic, but it also serves the logic of historical-materialist narration: the teacher attempts to enlighten, only to be silenced.

Ragbar Does Not Mean Just One Thing: Ambiguity in the Iranian New Wave

Unlike Soviet montage films, Downpour is not a straightforward piece of political agitprop. Instead, it unfolds as a dense network of competing meanings and narrative strategies. The film ends not with revolutionary victory but with defeat and departure. Iranian New Wave cinema drew inspiration from Italian neorealism and other emerging national cinemas. In this context, Downpour’s semantic ambiguity places it within broader trends in global art cinema, where openness and interpretive uncertainty were highly valued. While Beyzaie sometimes treats characters as class representatives—echoing early Soviet cinema—he continually destabilizes those roles, following the modernist trends of the 1960s and 1970s.

Even the film’s Persian title is ambivalent. Ragbar literally means “downpour” or “heavy rain,” referring to the scene in which Hekmati walks Atefeh home on a rainy night. The rain suggests an intense but fleeting wave of emotion, underscoring the melancholy transience of love. At the same time, ragbar also means “machine-gun fire,” linking the title allegorically to violent foreign intervention.

In one scene, television footage of the Vietnam War shows machine-gun fire from an American helicopter—an image resonant with Iran’s anti-imperialist sentiment at the time. Though brief and indirect, Downpour is among the earliest films to engage critically with the imagery of American helicopter operations in the Vietnam War. Western cinema had previously portrayed this war either propagandistically (The Green Berets, 1968) or neutrally (The Anderson Platoon, 1967).

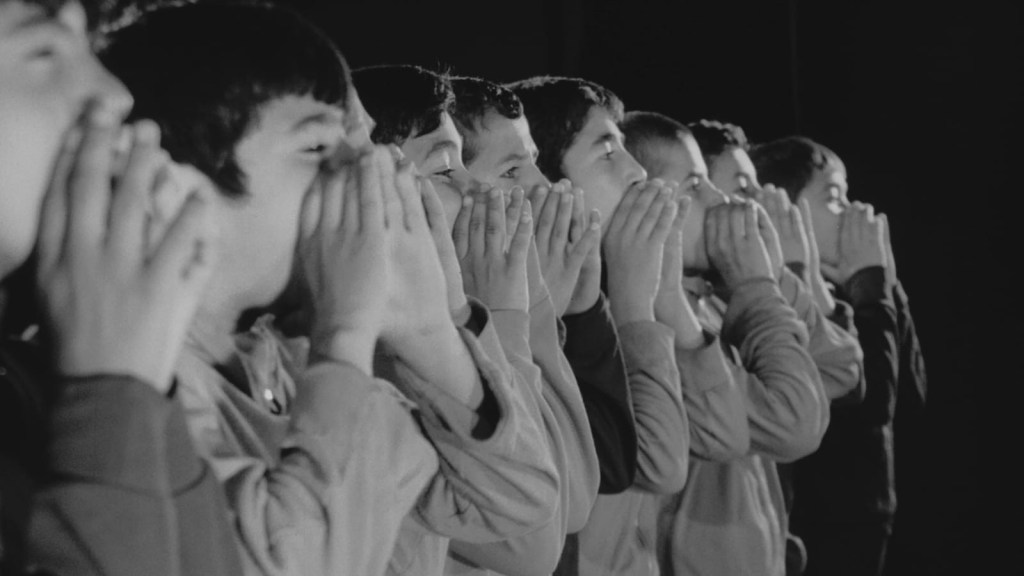

Ambivalence also characterizes the film’s portrayal of children. They do not function solely as symbols of oppression or surveillance; at times, they become agents of rebellion and even facilitate the bond between Hekmati and Atefeh. A scene in which boys shoot air rifles at a poster of a lightly dressed woman reads both as a critique of misogyny within traditional society and as a gesture of resistance against imported Western cultural norms.

This ambiguity serves multiple purposes. Modernism functions as Beyzaie’s cultural capital, allowing him to position himself within international art cinema while distancing his work from popular Iranian genre films (filmfarsi). At the same time, ambiguity offered protection from censorship—a common strategy in authoritarian contexts. Regulations prohibited inciting opposition to the monarchy and criticizing allied regimes.8

Crucially, ambiguity is not a modern Western import but a long-standing feature of Iranian artistic tradition. Medieval Persian poetry frequently employed deliberate double meanings through a technique known as iham. This device allows a single word to carry both an obvious meaning (qarib) and a concealed one (gharib)—the latter representing the poet’s true intent.9 Since poets depended on royal patronage, overt criticism could result in exile or worse. Iranian New Wave cinema naturally inherited this coded mode of expression—one already familiar to local audiences.

Downpour further masks its critique through comedy, another deeply rooted tradition in Persian culture. The 14th-century satirist Ubayd Zakani wrote texts that appeared playful or erotic on the surface but functioned as sharp social and political satire beneath.10

A similar strategy is at work in Beyzaie’s film. The final grotesque drunken brawl—styled as a parody of filmfarsi—culminates in Hekmati’s symbolic victory over the physically stronger Rahim. For an uninitiated viewer, Downpour may register as an experimental romantic tragicomedy about a weaker outsider confronting a more powerful rival. For those attuned to its codes, however, it remains a striking political allegory.

If my exploration of Bahram Beyzaie’s Downpour has inspired you, please consider supporting my work—every cup of coffee helps me continue writing about Iranian cinema. Feel free to share this article. Thank you for being part of this journey!

- https://www.film-foundation.org/world-cinema?sortBy=country&sortOrder=1&page=3 ↩︎

- David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 234–273. ↩︎

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS?locations=IR ↩︎

- Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 36. ↩︎

- Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 122–125. ↩︎

- Michael Axworthy, A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 240. ↩︎

- https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7121-downpour-furtive-glances ↩︎

- Hamid Reza Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 108–109. ↩︎

- Shahrou Khanjari, “Īhām, or the Technique of Double Meaning in Literature: Its Theory and Practice in the Twelfth Century,” Iranian Studies 56, no. 4 (October 2023), 459. ↩︎

- https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/obayd-zakani/ ↩︎

Leave a reply to 10 Essential Pre-Revolution Movies of the Iranian New Wave – Iran Zamin Cinema Cancel reply