Although the short film is officially classified as a documentary, Panahi’s past work invites us to question how much of what we see is carefully staged. He casts his daughter, Solmaz Panahi, alongside family friend and theater producer Shabnam Yousefi. Together they travel to a Kurdish village near Mahabad, home to a talented opera singer. Yousefi hopes to cast the young woman in an international project, but the singer’s family refuses to let her appear on camera. Left with no other option, Panahi decides to record her voice on site.

Thematically, Hidden recalls 3 Faces (Se rokh, 2018), in which Panahi examined the precarious position of actresses within Iran’s conservative social structures. This time, however, his focus shifts to opera—a genre effectively banned in Iran since the Islamic Revolution. The short film was originally commissioned by the Paris Opera as part of the anthology Celles qui chantent (dir. Julie Deliquet, Sergei Loznitsa, Karim Moussaoui, 2020).

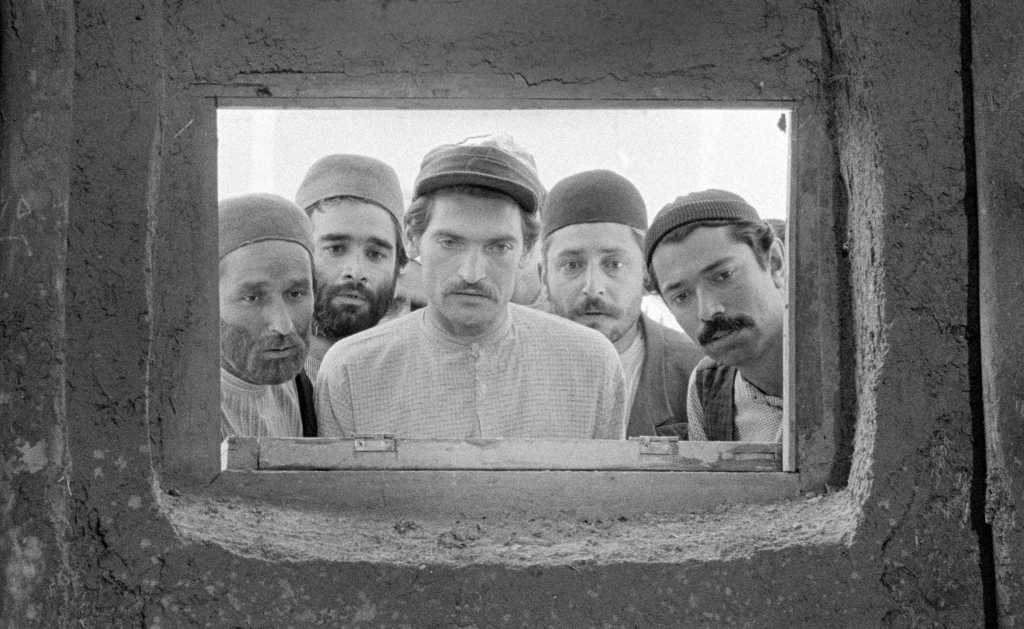

The movie is another example of Panahi’s characteristically uncomfortable yet remarkably inventive approach. Most of the action unfolds inside a car and is shot on two smartphones. Their presence is never concealed: one phone is attached at the front of the vehicle, while the other is held by Solmaz. Unlike in Panahi’s fiction films, this self-reflexive setup doesn’t feel distancing. Instead, it reinforces the documentary texture and the credibility of what we see. The sense of authenticity is heightened by the film’s structure as a single, uninterrupted journey, during which Yousefi describes the village’s patriarchal customs while guiding Panahi at the wheel.

Seemingly minor geographic references play a quiet but crucial role. The movie opens in medias res: Panahi and Solmaz sit in a parked car waiting for Yousefi, who is trying to locate them. Over the phone, she mentions that she’s standing at the Islamic Republic Square. Panahi clarifies his location, noting that it is near the City Hall—another emblem of state authority.

Shortly afterward, Yousefi appears in the frame almost accidentally aligned with a sadaqe (صدقه), a yellow-and-blue donation box for religious alms. The subtle motif may seem incidental, but alongside the earlier landmarks it becomes another coordinate marking the omnipresence of state power and theocracy. In Panahi’s hands, even the mundane act of navigation turns into a political statement.

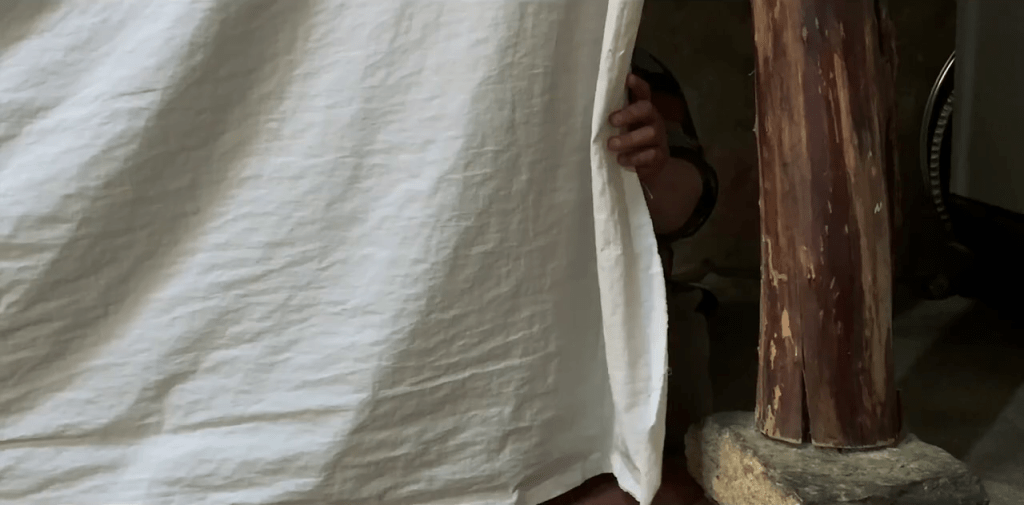

Upon arriving at the Kurdish family’s home, it becomes clear that the young singer is forbidden from revealing her face on camera. She is hidden behind a white sheet—a stark image that reveals the patriarchal logic governing even the private sphere of the household. After some insistence from the visitors, the family reluctantly agrees to at least allow her voice to be recorded.

The film’s final shot lingers on the white sheet, from behind which unexpectedly mesmerizing vocals emerge. The moment can be read as an act of quiet defiance, or perhaps as an indirect cry for help. As in 3 Faces, it leaves us with a profound sense of despair and compassion for a young woman trapped by rigid social norms.

From Politics to Aesthetics: An Explanation of the Cathartic Power of Music

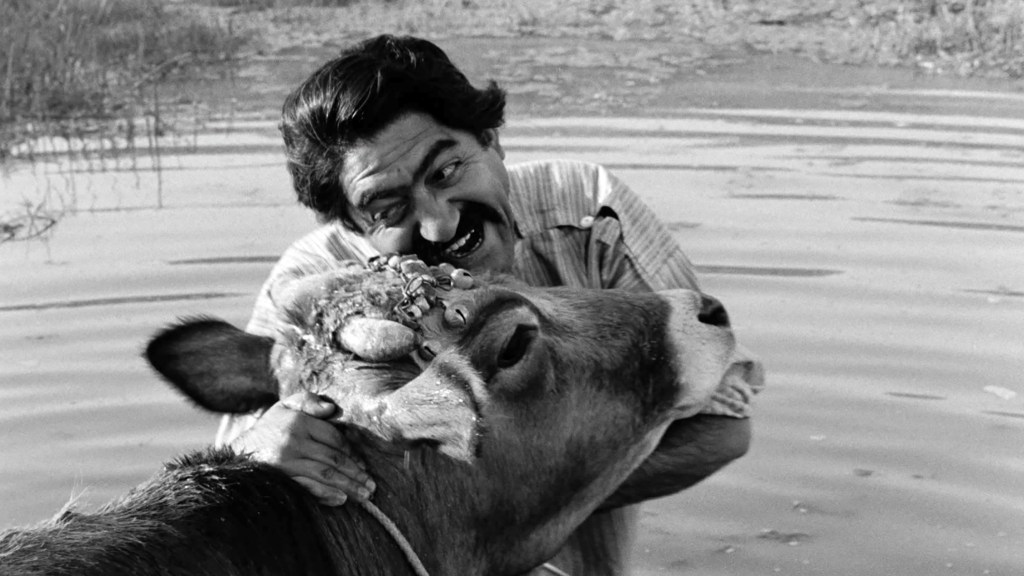

For all its darkness, Hidden ultimately offers a paradoxical sense of catharsis. One way to grasp this is through the philosophical distinction between the beautiful and the sublime, articulated by Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant. Beauty is tied to harmony, order, and calm—much like the serene landscapes in Abbas Kiarostami’s movies. The sublime, by contrast, emerges from an encounter with something overwhelming: something vast, strange, and awe-inspiring that confronts us with our own smallness. This is precisely the effect of the Kurdish girl’s singing. It is captivating and mysterious, and in a subtle way even unsettling.

The voice seems to come from another world. It suddenly rises out of the film’s report-like realism as a liberating force of art. Panahi’s narrative gradually moves from external symbols of the state and theocracy—the Islamic Republic Square, the sadaqe box—through the patriarchal norms of rural life, and finally toward a deeper meditation on the value of art itself. The final moment pulls us out of everyday, utilitarian thinking and leaves us with a lingering sense of transcendence.

What sets Hidden apart is its almost complete absence of the irony Panahi once used so frequently. Repressive norms are not undermined through satire here, but through the transcendent power of song. The apparent passivity of the girl behind the curtain is not a sign of helplessness. The sheet is not a real barrier—art speaks through it freely, finding its way despite obstacles.

In this shift from the political toward the aesthetic, Panahi—without abandoning his critical stance toward the social climate in Iran—moves closer to the poetic sensibility of Abbas Kiarostami. Where Kiarostami sought solace in the healing beauty of nature, Panahi finds catharsis in the sublime: in a voice that is not supposed to be heard, yet resonates all the more powerfully because of it.

If you found my review and explanation of Jafar Panahi’s movie valuable, please consider supporting this blog. Every share or even a small donation helps keep it going.

Leave a comment