This is the first part of a two-part study devoted to the analysis and interpretation of one of the most important films in the history of Iranian cinema.

Iranian cinema of the 1950s was defined primarily by popular entertainment. Government-backed commercial films were dismissively labeled by critics as filmfarsi (Persian-language films). The narratives of popular melodramas relied on implausible plots, unexplained coincidences, and escapist fantasies.1 A major shift occurred in the 1960s, when modernist aesthetics began to enter Iranian cinema as an alternative to state-supported production. Following the example of European cinemas, a new trend emerged that came to be known as the New Wave, or Iranian New Cinema.

Significant modernist traits were already present in the documentary The House Is Black (Khaneh Siah Ast, 1963), filmed in a leper colony and directed by the nonconformist poet Forugh Farrokhzad. Despite its striking formal qualities, the documentary had less influence on Iranian cinema than several other films of the period. Masoud Kimiai’s Qeysar (1969) and Dash Akol (1971) proved more influential, at least in the sense that they helped establish the conventions of the tough-guy subgenres jaheli (stories set in the modern era) and dash mashti (historical stories from the pre-modern period).2

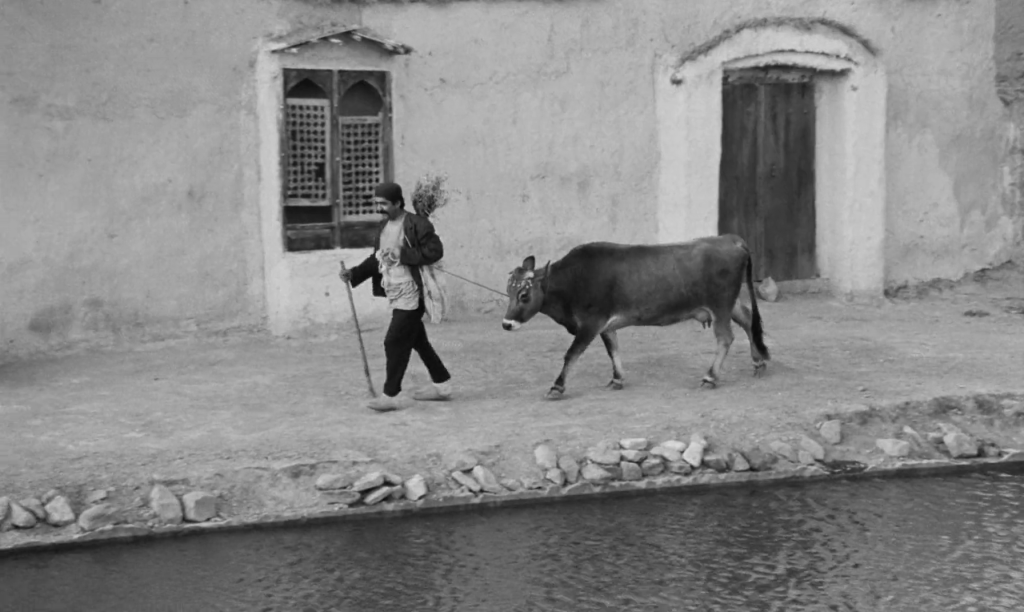

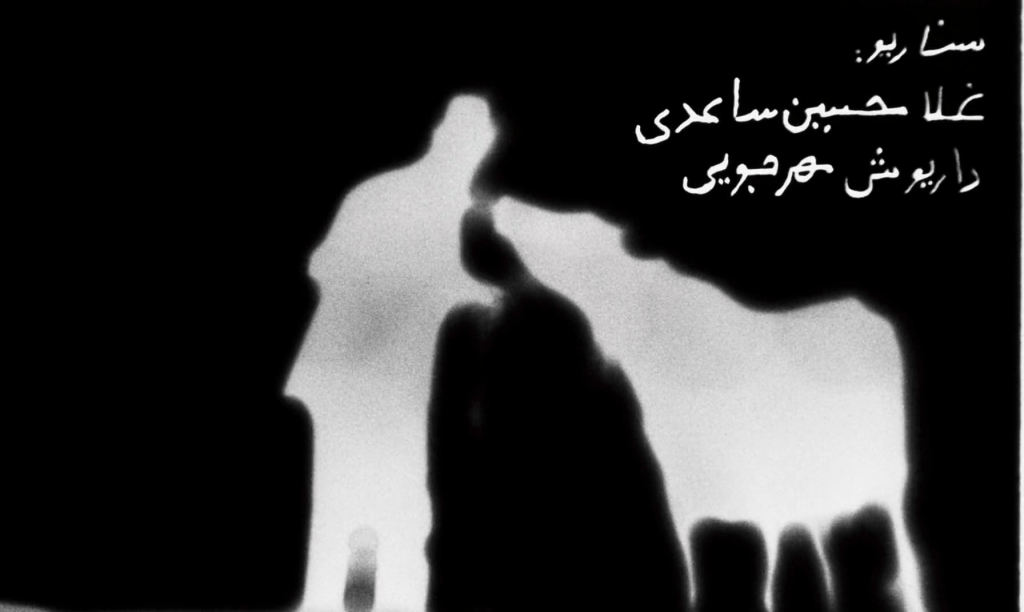

The most influential movie of the decade—and arguably one of the most important Iranian films ever made—was The Cow (Gaav, 1969), directed by Dariush Mehrjui. The film absorbed modernist aesthetics and established several defining features that would shape later Iranian New Wave works. The entire story is set in a small village. Masht Hassan is the only villager who owns a cow, a fact that fills him with pride. During a short trip to the city, the cow dies. The villagers bury the animal and agree, out of compassion, to hide its death from Masht Hassan. Instead, they tell him that the cow has run away.

Masht Hassan is unable to accept the loss and gradually descends into madness. He begins to identify with the beloved cow, moves into the stable, and eats hay. Disturbed by their inability to help one of their own, the villagers decide to take the delirious man to a hospital in the city. During a frantic escape attempt, Masht Hassan dies tragically before the men even reach their destination.

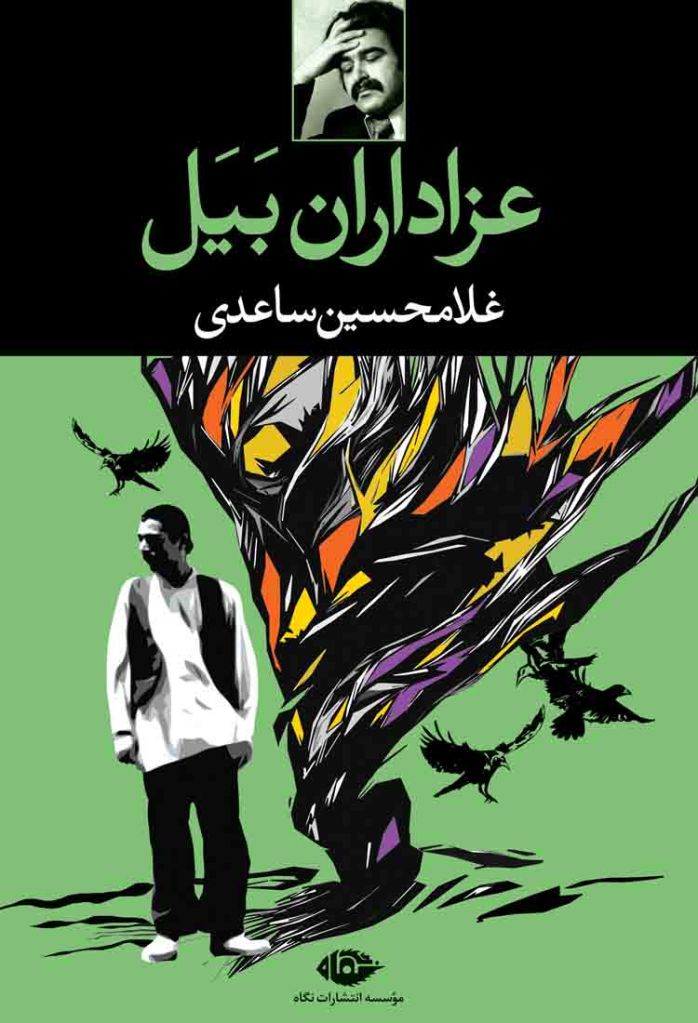

Adapting Sa’edi: From Short Story to Iranian Movie

The Cow is an adaptation of a short story by Iranian writer Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi from the collection The Mourners of Bayal (Azadaran-e Bayal, 1964). Sa’edi, who also co-wrote the film’s screenplay, became known as one of Iran’s leading dissident authors. His opposition to the Shah’s regime led to repeated arrests and torture by the secret police, SAVAK. Literary critics often described Sa’edi’s stories as “cinematic,” a claim supported by the fact that two of his other works were later adapted for the screen: Tranquility in the Presence of Others (Aramesh dar hozur-e deegaran, 1972), directed by Nasser Taghvai, and Mehrjui’s The Cycle (Dayere-ye mina, 1974). Trained as a physician, Sa’edi worked as a psychiatric researcher and developed an informed understanding of rural life, which proved invaluable in his fiction.3

The title The Mourners of Bayal refers to the fictional Iranian village of Bayal. In addition to sharing a setting and recurring characters, the untitled stories are united by themes of death and other misfortunes. Each story brings different protagonists to the forefront. Using a restrained, realist style, Sa’edi depicts the everyday routines and rituals of the villagers of Bayal.

Much like Iranian New Wave films, the realism of several stories is interwoven with mystical or surreal elements and a subtle sense of lyricism. In the first story, mysterious bell sounds foreshadow the death of a sick woman. In the seventh story—reminiscent of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (Die Verwandlung, 1915)—people transform into strange creatures. Mehrjui’s The Cow is primarily based on the fourth story, while also borrowing and reworking motifs from others. The filmmakers created a relatively faithful adaptation but added scenes that emphasize the bond between Masht Hassan and the cow, expanded the themes of madness and violence, and toned down certain naturalistic elements.

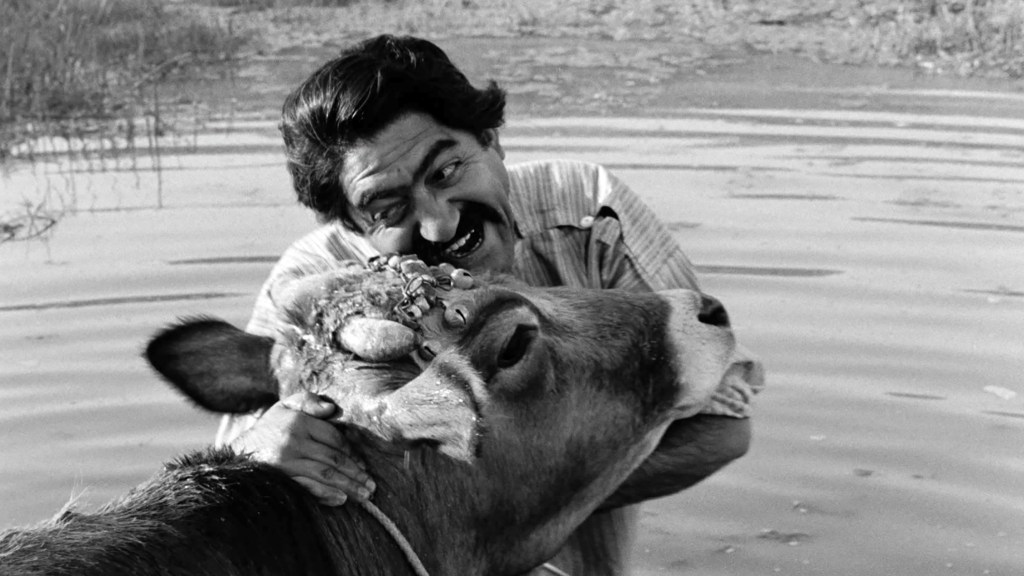

The main difference between the film and its literary source lies in the exposition. The short story begins abruptly, with the lament of Masht Hassan’s wife shortly after she discovers the dead cow. The film’s opening scenes—set before Masht Hassan leaves for the city and designed to deepen his affectionate relationship with the cow—are absent from the text. Moments such as bathing the cow in a pond, Masht Hassan sleeping in the stable (choosing the animal over his wife), or the motif of a gift (a necklace) for the cow do not appear in the story. There, Masht Hassan’s attachment to the animal is only hinted at when his brother-in-law remarks, “I know Masht Hassan loves his cow much more than my sister.”4 By adding these scenes and motifs, Mehrjui underscores the emotional bond between man and animal, suggesting that the cow is more precious to Masht Hassan than his wife and thereby clarifying the roots of his later psychosis.

Another character introduced in the film is the village madman, whose torment opens the story. His suffering brings a powerful social critique into the film. Mashadi Safar’s son—a young man who takes pleasure in cruelty—smears black tar on the madman’s face while he is tied up, puts a ridiculous hat on his head, and then burns him with flaming torches. Children and adults alike watch the groaning man as if he were harmless entertainment. A cowbell tied to the trembling madman as a mark of humiliation foreshadows Masht Hassan’s later social exclusion.

Later, the villagers realize that the madman might reveal the cow’s death to Masht Hassan. To prevent this, two men drag him to an abandoned mill and tie him to a massive millstone. These motifs expose the villagers’ ostracizing attitude toward unconventional behavior. Although Sa’edi’s story about the cow does not include these scenes, the cruelty of the people of Bayal—especially Mashadi Safar’s son—appears elsewhere in the collection. The film’s image of the madman bound to the millstone loosely reworks motifs from the later seventh story.

Mehrjui’s critical emphasis on violence is also evident in the scene where Masht Hassan is tied with a rope while resisting capture. As three men escort him toward the city, Eslam—who otherwise appears the most moral and compassionate among them—erupts in rage and brutally drives Masht Hassan forward with a wooden stick like a disobedient animal. Masht Hassan then breaks free, flees in panic, and dies after falling into a ravine. In the book, we find no direct depiction of the binding, beating, or the protagonist’s death. The struggle between the three men and their frantic companion is suggested only indirectly: “The cow, with its small body, resisted and exhausted the men.”5 The narrator’s use of the word “cow” may indicate that the literary characters succumbed to a similar delusion as the film’s Eslam, ultimately identifying their companion with the animal as well.

Another change concerns the presentation of the bandits. Throughout the collection, there are references to the neighboring village of Poros, from which bandits ride out to raid surrounding farms. In the villagers’ accounts, they appear as mysterious and feared figures, yet the reader learns little about them. The closest encounter comes in the third story, where two villagers secretly travel to Poros to retrieve stolen property. Although the film also incorporates elements from this story (two men travel to a neighboring village), it omits any direct excursion into the bandits’ territory.

Mehrjui strips the bandits of clear contours, making them even more enigmatic than in the source material. In the film, they appear as a trio of men, often standing in the distance on the horizon like silhouettes. The most striking change, however, is the renaming of the people of Poros as the Bolurs (“Crystallines”). This cryptic name enhances their mystery and invites multiple interpretations. A similar effect is achieved by omitting the name Bayal altogether. While Bayal is a fictional village in the book, it can feel like a real place to the reader. In the film, the name Bayal is never mentioned, even though other villages are named.

In his adaptation, Mehrjui emphasized madness and violence while eliminating certain naturalistic details. For example, the opening lament of Masht Hassan’s wife in the short story is accompanied by a graphic description: “A chicken carcass floated in the pool, and fish circled it, swallowing bits of fat drifting on the surface.”6 The carcass remains in the pool for most of the story. Only days later do we read: “Mashadi Safar’s son fished the chicken’s corpse out of the pool with a long stick.”7 In the film, we see the young man poking the water with a stick, but without clear purpose, the water in the pool being clear.

The mystification of the Poros bandits, their renaming as the Bolurs, the omission of the village name Bayal, and the suppression of certain naturalistic details give the film a more abstract and sterile quality. It can be argued that these changes expand the interpretive potential of Mehrjui’s adaptation.

The Question of Realism in The Cow

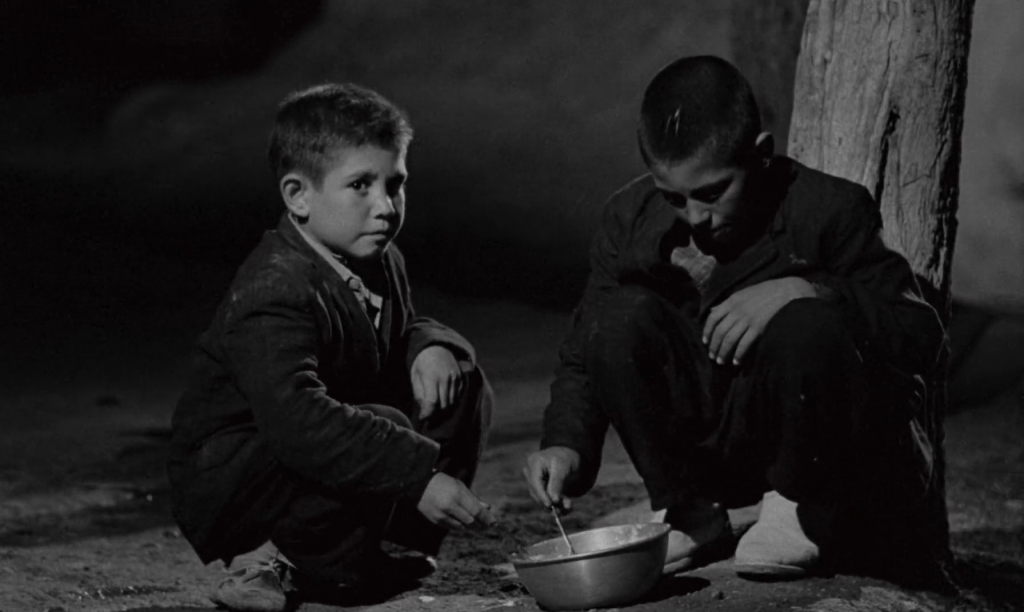

By focusing on rural life, Mehrjui departed from the conventions of popular filmfarsi cinema and from Kimiai’s films about indestructible tough guys. Rural settings emerged as a refreshing counterpoint to commercial narratives centered on urban life and modernity. This turn toward the countryside also meant a focus on the poor, who made up the majority of the country’s population. Poverty in The Cow is not portrayed as dignified or innocent, but as bitter and desperate. In one nighttime scene, two small boys squat in the street, eating from a single bowl placed on the ground. This unembellished depiction of rural life corresponds to what film historians David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson describe in postwar European cinema as objective realism,8 a mode that fully emerges in Italian Neorealism.

Yet The Cow is not a typical realist film. Unlike some neorealist works, Mehrjui did not cast non-professional actors in the main roles, but instead relied on trained theater actors from the Ministry of Culture and Arts. The film’s complex psychological narrative required professional acting, which ultimately strengthened its credibility. Ezzatollah Entezami convincingly portrays Masht Hassan’s devoted love for the cow and his obsessive delusion. In scenes of communication and physical closeness with the animal, Entezami persuasively conveys the intimate bond between human and animal.

Entezami moves through a wide vocal range, from animal-like cries to the mystically calm declaration, “I am not Masht Hassan, I am Masht Hassan’s cow.” At this moment, the viewer is left uncertain whether the protagonist’s unusual behavior stems from mental illness or from a strange spiritual state.

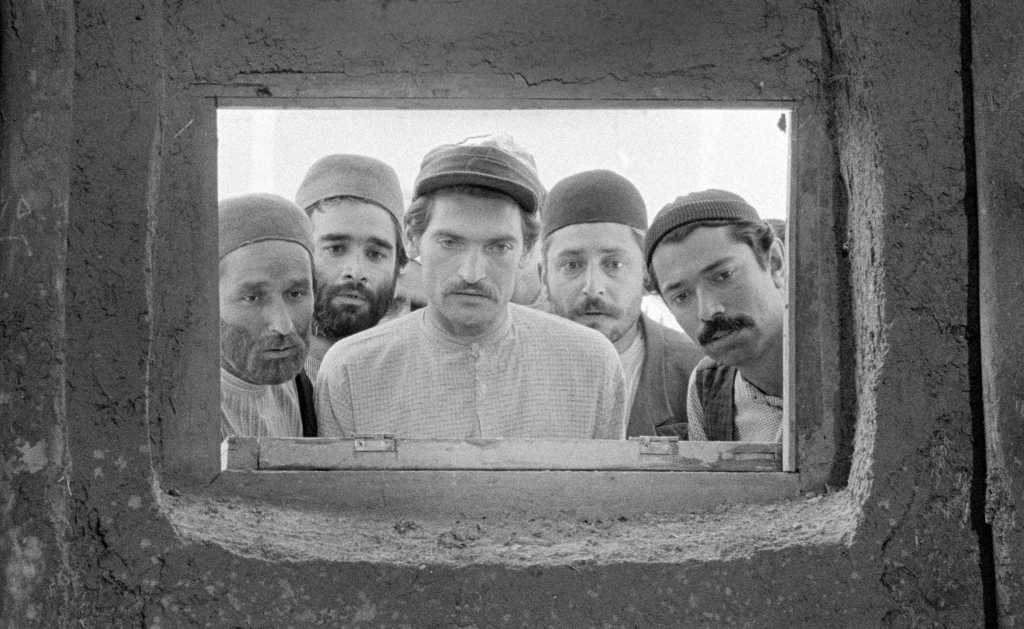

The main actors, all of whom came from a theatrical background, had previously staged Sa’edi’s story about the cow as a television production before the film was made. Traces of this theatricality can still be seen in some scenes of Mehrjui’s adaptation. At the beginning of the film, when five men sit on a terrace, their declamatory reactions resemble stage performance more than naturalistic film acting. Other moments, however, feel closer to neorealism. The scene of Masht Hassan’s wife lamenting is a realistic crowd situation in which the spontaneous reactions of villagers come to the fore. Using rural extras brings authenticity through the aged faces captured in close-up shots.

Stylistic Innovations of the Iranian New Wave

With this film, Mehrjui offered an unusually authentic perspective for its time. At the same time, he occasionally employed narrative parallelism and expressive stylization typical of cinematic modernism. A key parallel is established between the burial of the cow and Masht Hassan’s death. Another clear analogy emerges between the trio of men—the village headman (kadkhoda), Eslam, and Abbas—who attempt to take their mad companion to a city hospital, and the three feared Bolur bandits, who watch from afar without intervening. This visual variation suggests that the real threat to the protagonist is not the passive bandits, but his closest companions.

Beyond narrative parallelism, Mehrjui also applies artistic stylization to elements of the mise-en-scène. The opening title sequence presents Masht Hassan and his cow in a sharply contrasted image that distinctly separates black and white. This color dichotomy is later echoed throughout the mise-en-scène. Particularly striking are the mud walls of rural houses painted bright white and illuminated by harsh sunlight. The opposing black appears in several nighttime scenes and in the dark chadors worn by women mourning at the cemetery.

In his adaptation, Mehrjui leans toward what Bordwell and Thompson call subjective realism,9 another key feature of postwar cinema alongside objective realism. European modernist filmmakers often used specific techniques to intensify characters’ mental states. In The Cow, subjective realism does not take the same form as in films such as Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), where Alain Resnais enters the characters’ inner worlds through flashbacks. Mehrjui’s camera always observes Masht Hassan from the outside and never directly conveys his distorted perception of reality. Nevertheless, Mehrjui employs stylistic devices that allow the viewer to empathize with the experiences of a man sinking into madness—or, conversely, into a strange state of bliss.

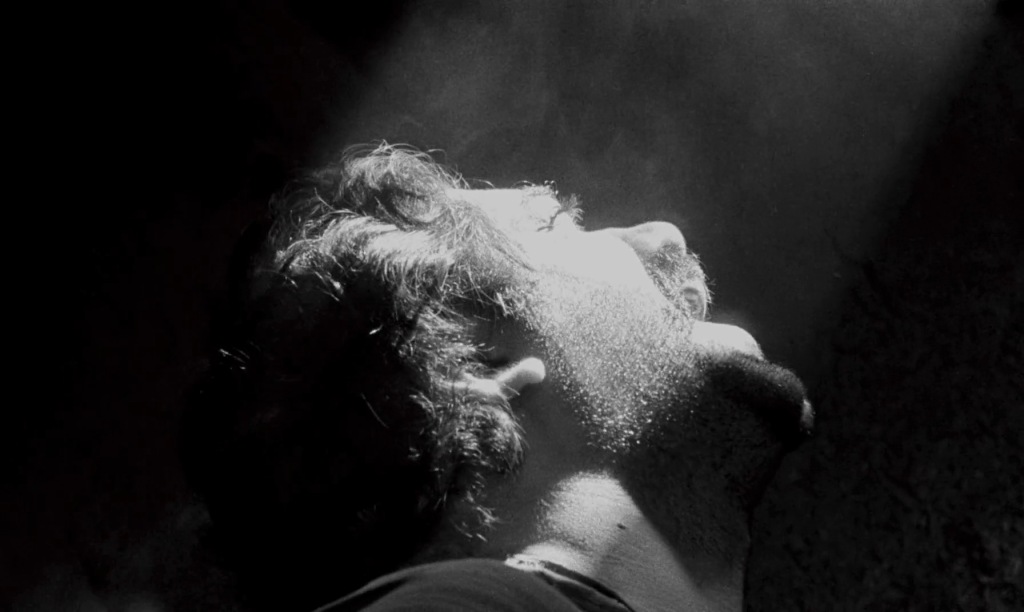

When Masht Hassan lovingly washes his cow in a pond, he is followed in a prolonged sequence of handheld shots. Only later, when the trio of Bolur bandits appears on the horizon, are we—along with the protagonist—pulled out of this subjective immersion. A similar approach is used in later scenes in which Masht Hassan begins to identify with the cow. When he cries out for help in terror inside the stable, he is filmed with a handheld camera and captured in a series of short shots from different angles. This editing pattern helps the viewer enter the psyche of a character experiencing paranoia.

In a later scene, Masht Hassan runs around inside the stable like a wild animal. This time, the circling camera movements are combined with dissolves, creating a hallucinatory effect that suggests the climax of his madness. Together with the unsettling musical score, the scene is deeply disturbing and transmits the subjective experience of the tormented character to the audience. Mehrjui uses these expressive techniques carefully and integrates them skillfully into an otherwise realist style.

Religion plays a specific role in The Cow. It is already strongly present in the literary source and deepens both the realist and subjective dimensions of the film. Religion is neither idealized nor portrayed as a comic relic of outdated traditions. It is not necessarily institutional or formal, but rather an authentic expression that includes informal folk elements. In The Cow, one can observe Shi’a Muslim iconography, most notably in the evocative scene of nighttime mourning. Religious banners topped with copper hands reaching toward the sky cast expressive shadows on a white wall. The fearful gazes and weeping of the villagers evoke the emotional expressions of Shi’a piety, rooted in a long tradition of martyrdom.

Like European modernist filmmakers, Mehrjui strives for artistic complexity through a combination of objective and subjective realism. The strength of his craft lies in portraying inner disintegration and the suggestive power of religion without excessive pathos or mannerism. Compared to Forugh Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black, his style is less progressive, yet within the context of Iranian cinema of the time it remains notably innovative and tastefully balanced. Mehrjui often relies on simple techniques, such as the exchange of silent glances between characters. Indirectly, he reveals relationships, fears, and uncertainties without using to verbose dialogue.

In the next part of this study, we move beyond the analysis of cinematic form of this Iranian movie. We examine how Mehrjui’s The Cow was received in its time and, above all, how it can be interpreted in multiple ways—from political allegory to Sufi mysticism.

Writing this article took a lot of time and effort, including studying Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi’s work in its original Persian. If you found this analysis meaningful, please consider supporting the blog on Buy Me a Coffee.

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 149–154. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 269–270. ↩︎

- https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/saedi-gholam-hosayn/ ↩︎

- Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, Azadaran-e Bayal (Tehran: Mo’asese-ye entesharat-e negah, 1400 [2021]), 105. ↩︎

- Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, Azadaran-e Bayal (Tehran: Mo’asese-ye entesharat-e negah, 1400 [2021]), 115. ↩︎

- Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, Azadaran-e Bayal (Tehran: Mo’asese-ye entesharat-e negah, 1400 [2021]), 96. ↩︎

- Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, Azadaran-e Bayal (Tehran: Mo’asese-ye entesharat-e negah, 1400 [2021]), 112. ↩︎

- Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003), 441. ↩︎

- Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003), 441. ↩︎

Leave a comment