Thanks to a digitally restored version by the UCLA Film & Television Archive, now being shown in cinemas again, this overlooked gem of pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema has a chance to reach a new and wider audience. The film’s distribution is handled through a co-release by Arbelos and Venera Films.

Nabili studied film in London and New York before returning to Iran in the 1970s. There, she made her graduation film, The Sealed Soil (Khak-e Sar be Mohr, 1977)—a work that eventually became her only film. It was filmed secretly in a village in southwest Iran. At that time, the Shah’s regime allowed rural life to be shown only in terms of progress and modernization; any critical view was forbidden. Nabili therefore smuggled the footage to the United States, where she completed the final cut. Although the film was never officially released in Iran, it was screened on several occasions in the U.S. shortly after it was made.

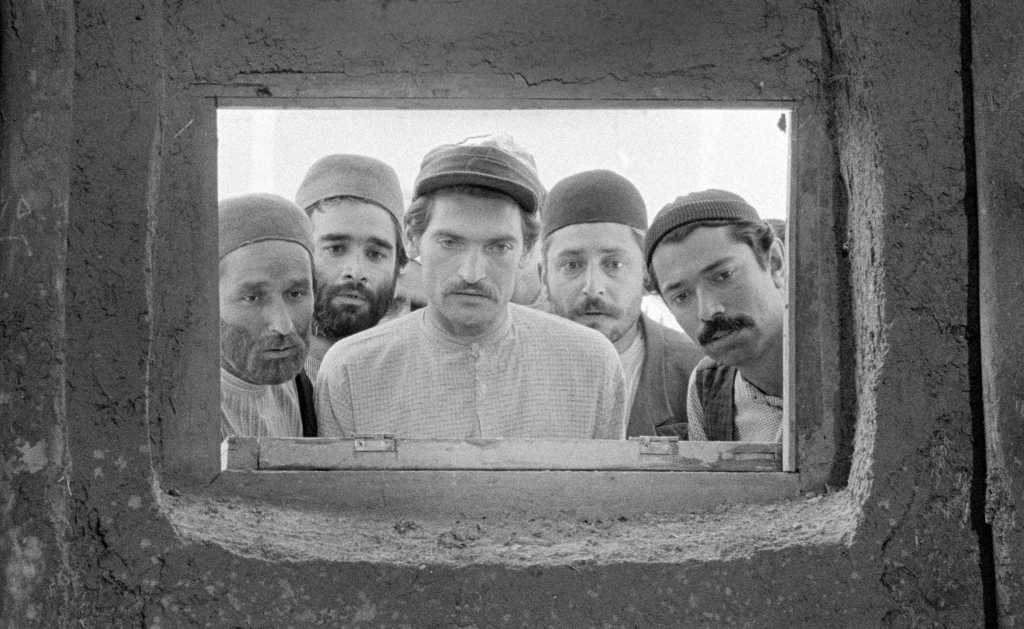

The Sealed Soil tells the story of 18-year-old Rooy-Bekheir (Flora Shabaviz), a young woman living in the Iranian countryside. She constantly rejects marriage proposals while her village faces forced relocation as part of a modernization project by a large agricultural company. Rooy-Bekheir resists both the traditional expectations of marriage and the pressure to leave her home. Her defiance eventually leads to an emotional breakdown, which the villagers interpret as possession. The film captures the tension between tradition and modernity, and between individual freedom and the burden of collective identity.

The Sealed Soil, a striking example of slow cinema, recalls Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) by Belgian director Chantal Akerman—especially in its focus on the monotonous life of a woman overwhelmed by domestic work. The film also shares similarities with Still Life (Tabiat-e Bijan, 1974) and A Simple Event (Yek Etefagh-e Sadeh, 1974) by Iranian director Sohrab Shahid Saless, who, a year before Akerman, defined his own unique slow cinema style. The camera captures Rooy-Bekheir’s daily routine—washing dishes in the river, sifting grain, gathering plants—as a repetitive rural ritual.

Nabili deliberately avoids traditional storytelling by omitting key narrative events. Exactly halfway through the film, there is an almost imperceptible time skip—a whole month passes. During this gap, Rooy-Bekheir meets one of her suitors—a moment that would normally be central in a conventional plot. Here, however, it is completely omitted and only mentioned briefly in dialogue. After the time skip, the film smoothly returns to the everyday routine, without suggesting that anything has changed.

The director uses her background in painting to shape the film’s visual style. Rural life is shown in carefully composed static shots. This observational and distant style creates a strong sense of alienation. That feeling is deepened by the sparse, fragmented dialogue, reminiscent of the austere style of Robert Bresson. This restraint makes the one stylistic shift stand out: when Rooy-Bekheir is captured in a close-up with a handheld camera—for the first and only time.

Instead of focusing on dramatic storytelling, the film explores the possibilities of cinematic style. Long takes give viewers time to observe changes in light throughout the day and the movement of shadows on mud-brick walls. The repetitive patterns of daily life are accompanied by the sounds of birds, adding to the rhythmic harmony of the rural space. Especially striking are the moments when Rooy-Bekheir walks slowly while cars rush past her. This contrast of speed is not just a visual gesture—it also expresses the tension between tradition and modernity that defined the period when the film was made. This tension is a key theme in Iran’s pre-revolutionary New Wave cinema.

The film should be understood in the context of its time. It was made during the so-called White Revolution—an ambitious modernization initiative launched in 1963, aimed at transforming Iranian society and economy, while also strengthening the Shah’s power. Although the reforms promised better living conditions, in reality they often deepened social inequalities.

Wealth increasingly concentrated at the top of society and rarely reached the lower classes. In the 1970s, Iran had one of the worst income distributions in the world. Most rural areas still lacked electricity, schools, running water, roads, and other basic services.1 This desperate socio-economic context helps us understand the theme of marriage in The Sealed Soil. For a rural woman, marriage was often a matter of survival. This reality is powerfully described in Mahmoud Dowlatabadi’s novel Missing Solouch (Ja-ye Khali-ye Soluch, 1979), which portrays rural poverty of that time with raw intensity.

In The Sealed Soil, the social system is not shown as a mechanism of male dominance imposed from outside. Rather, it works as a complex structure that is also actively shaped by women themselves. The protagonist’s mother, neighbors, and younger sister all repeatedly pressure her to marry. Female characters are not just victims of male oppression—they also help create the norms they see as necessary for survival in the harsh rural environment. In doing so, the film opens a deeper reflection on how gender roles are not only passively accepted but also co-created by those who suffer from them—making feminist interpretations of the film more complex.

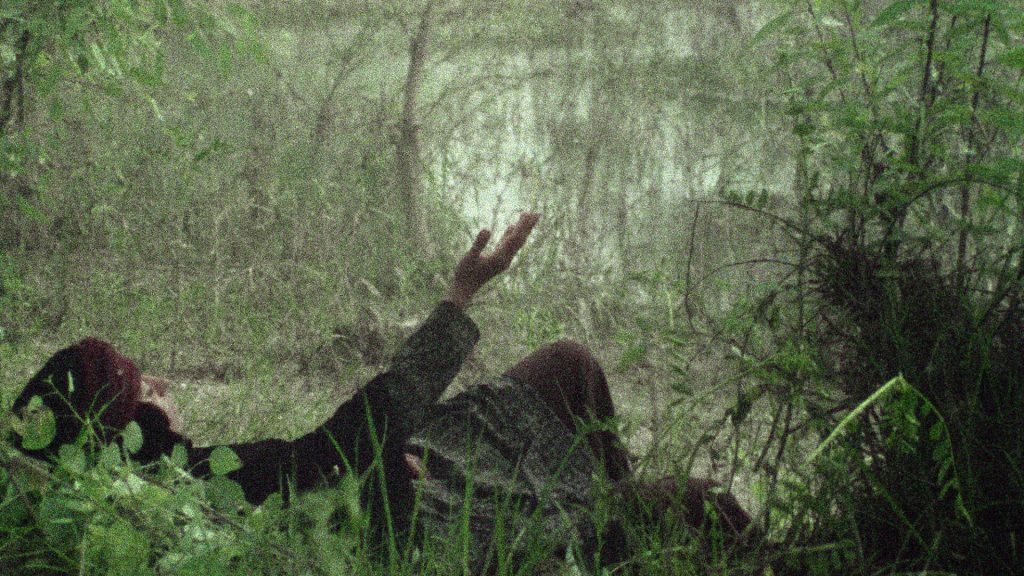

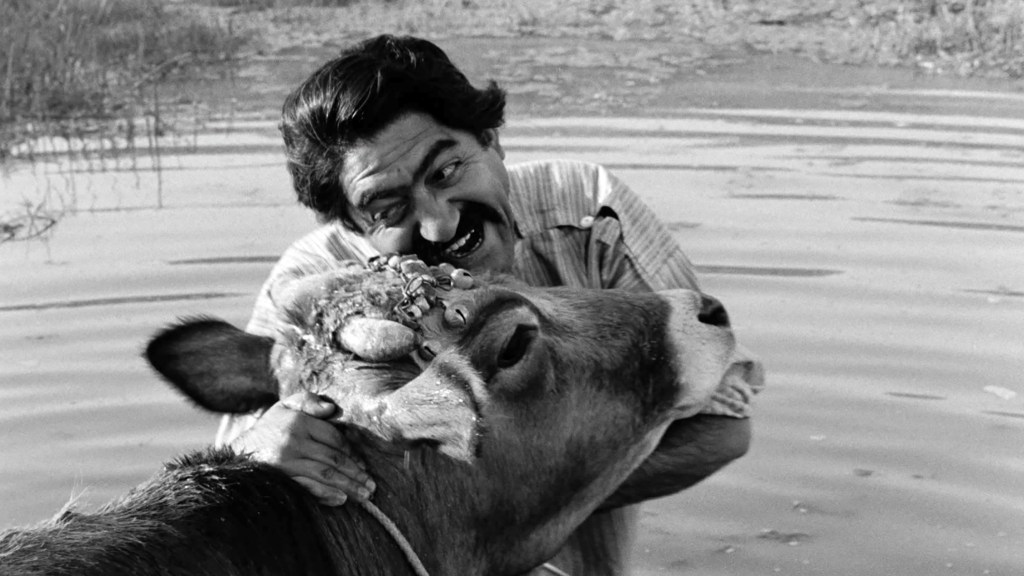

Nabili’s film feels like an open work of art that resists a single, fixed meaning. Does the protagonist find inner peace in her moments of stillness? Or does she experience unbearable existential boredom? Is her relationship to nature a form of meditation, or a sign of a disturbing contradiction—as suggested by the moments when she treats animals cruelly? This modernist ambiguity invites the viewer to develop their own interpretation. The Sealed Soil remains not only a rare document of its time, but also a film that quietly asks questions that continue to resonate long after the screening ends.

If you enjoy this content, please consider supporting my independent writing on Iranian cinema. Every contribution is deeply appreciated.

- Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 143–146. ↩︎

Leave a comment