The film debuted internationally to extraordinary acclaim. It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, becoming the second Iranian film to take the festival’s top prize after Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry (Ta’m-e gilas, 1997). It was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best International Feature and Best Original Screenplay. Had it won, it would have joined A Separation (2011) and The Salesman (2016) by Asghar Farhadi—and the animated short In the Shadow of the Cypress (2023)—among Iran’s Oscar winners. Ironically, however, It Was Just an Accident (Yek tasadof-e sadeh) was submitted to the Academy not by Iran, but by its co-producing partner, France—an apt reflection of Panahi’s uneasy relationship with his home country’s official cultural institutions.

That ambivalence is embedded in the film’s very production. Shot secretly in Iran without government approval, It Was Just an Accident continues Panahi’s long-standing strategy of working within severe limitations. Once again, he turns the car into a kind of mobile private studio, employs a small cast, and situates the story in remote locations. This time, the stark desert landscape forms a striking counterpoint to the psychological confinement of imprisonment that the film explores.

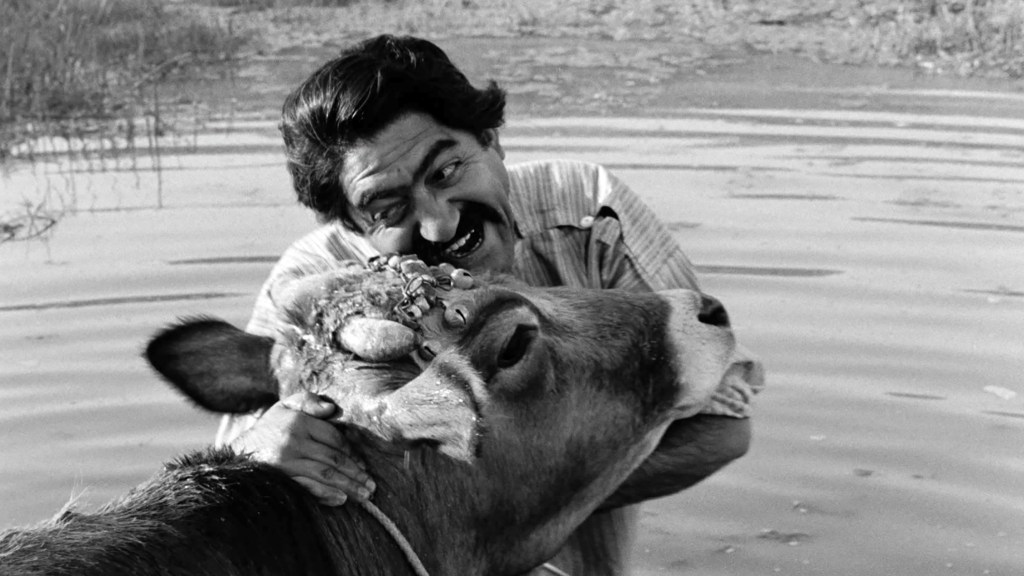

The story follows Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri), a former political prisoner now working as an auto mechanic. When a man with a prosthetic leg shows up at his garage, Vahid becomes convinced he has encountered his former torturer, a secret service officer named Eghbal (Ebrahim Azizi). The sudden encounter reawakens Vahid’s trauma and drives him toward a desperate act that sets off a chain of morally fraught situations. And yet, surprisingly, the film often veers into dark comedy—at times bordering on farce.

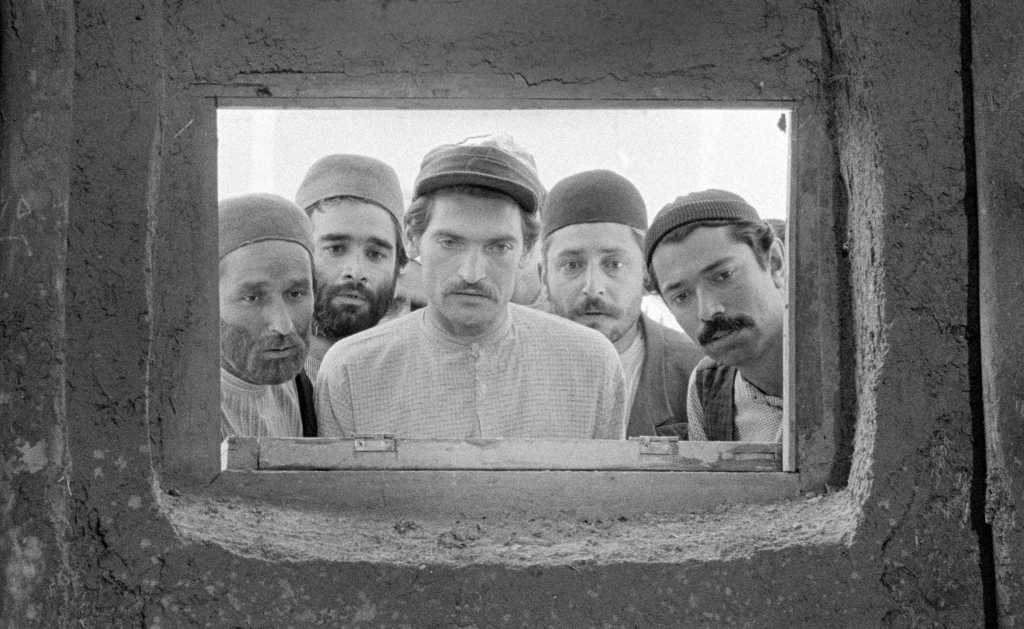

Vahid isn’t even certain he has the right man; during interrogations, he never saw his torturer’s face. To confirm the identity of the alleged Eghbal, he seeks out other former prisoners. The film gradually transforms into a road movie about memory, justice, and doubt. Panahi confronts us with a paradox: Are you truly free when you leave prison if your mind is still trapped by trauma and anger? Or does real freedom lie in an inner autonomy that can survive even physical captivity?

Language carries its own quiet significance, including the film’s sharp, ironic use of Persian swear words. In two scenes, Vahid speaks Azerbaijani with his mother—a subtle reference to Panahi’s own ethnic background and an autobiographical trace. The film leaves open the question of how deeply the characters’ prison trauma echoes the director’s own experience.

Despite its heavy themes, Panahi avoids solemnity. As in 3 Faces (Se rokh, 2018), he infuses the narrative with irony and satire. The opening scene uses dance and music as gestures of defiance—a motif he has explored before, notably in Hidden (2020) and Offside (2006), the latter provocatively incorporating an Iranian pre-revolutionary patriotic song. Here, theatricality becomes increasingly pronounced, culminating in the final confrontation with Eghbal. The stylization recalls absurdist drama: grotesque situations gradually expose the futility of resisting a single individual who is wholly devoted to a repressive system. Violence loses any heroic aura and becomes a moral trap.

Female characters play a crucial role. They appear without hijabs or with loosely worn scarves, reflecting the current Iranian reality in which the hijab has become a focal point of public resistance. Shiva (Mariam Afshari) serves as the rational voice, resisting the lure of simple revenge. Goli (Hadis Pakbaten), by contrast, is passionate and openly vengeful—yet in moments of crisis, she reveals unexpected compassion, challenging predictable character roles.

The Ending Explained: Symbolism of Dogs and Birds

Seemingly subtle yet central to the film are its recurring animal motifs—dogs and birds. Panahi employs them in a way reminiscent of Romantic artistic tradition, where nature functions as an ethical commentary on human action. Over time, Vahid begins to realize that inner spiritual freedom surpasses the external freedom denied to him by political power.

In the opening scene, Eghbal runs over a dog with his car. His daughter reacts with grief and reproach; he dismisses it as a meaningless accident. The motif returns when Vahid is on the verge of carrying out his revenge, only to be interrupted by the sudden appearance of another dog. The opening and one of the final scenes are also connected through lighting: in both, Eghbal is lit by an intense red glow. The blood-red tone creates a symbolic “hell,” a space where characters must confront their guilt and decide whether to repeat violence or reject it.

Birds form the second major motif. They first appear in Vahid’s garage, where a group of pigeons flutters around inside their cage when the lights are switched on. Later, the sound of cawing crows disrupts what should be a joyful wedding photo shoot, introducing an ominous undertone.

The third—and most significant—appearance is in the final shot. We watch a nervous Vahid listening for the distinct mechanical rhythm of Eghbal’s prosthetic leg. That harsh, unpleasant sound gradually fades and is replaced by the gentle chirping of birds, continuing over the end credits until the very last second of the film. The audience may expect another cue—perhaps Eghbal speaking—but it never appears. Nature’s soundscape overtakes human presence and the mechanical sound of the prosthetic leg.

In this closing gesture, Panahi shifts the narrative’s center of gravity from explicit political conflict to the connection with nature, evoking the poetic sensibility of Kiarostami. This is not new terrain for Panahi: in his documentary Life (2021), he found a moment of redemption in observing a bird being born during the pandemic.

In It Was Just an Accident, however, the gesture becomes an ethical stance. Panahi does not triumph over the repressive system through direct confrontation, but through an affirmation of life as a fundamental moral principle. Dogs and birds are not decorative details; they function as a quiet moral compass, guiding both the characters and the audience toward a choice other than revenge. Yet the cycle of state repression remains unbroken—the protagonist’s trauma isn’t resolved, only something they must learn to live with. This unresolved conflict serves as a reminder that real change is often slow and uncertain.

Panahi constructs a moral experiment in which political trauma becomes an existential question—and a search for inner freedom. Beneath its apparent simplicity lies a carefully woven symbolic structure. And once again, Panahi’s most radical act is simply this: the insistence on telling a story, even under conditions designed to silence him.

If you found this review valuable, please consider supporting my blog. Every share or even a small donation helps keep it going.

Leave a comment