With this archetypal, myth-inflected work, Bahram Beyzaie (sometimes transliterated as Beyzai) partially turns away from the political allegory of his earlier Downpour (Ragbar, 1972). When The Stranger and the Fog premiered at the Tehran International Film Festival in 1974, some critics praised its technical sophistication, but the broader critical response in Iran was muted. At the time, leftist film criticism favored explicitly social and political narratives.1 In retrospect, however, the film stands out as a misunderstood achievement—one that now clearly belongs in the core canon of Iranian cinema and ranks among the finest works of the pre-revolutionary New Wave.

Following Downpour, The Stranger and the Fog is the second Beyzaie movie to be restored under Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. The restoration was completed in 4K from the original negatives, with Beyzaie himself supervising the color grading.2

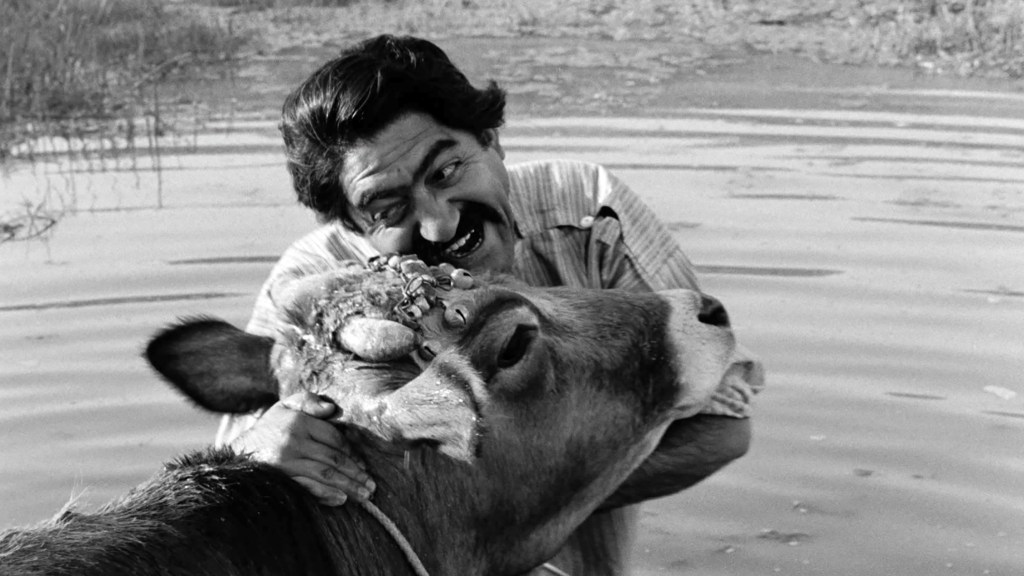

Set on Iran’s northern coast in a fictional village perpetually shrouded in fog, the film unfolds like a modern myth. Rana (Parvaneh Massoumi) has been waiting for a year for her husband, lost at sea. When a boat finally reaches the shore, it carries not her missing spouse but a wounded stranger named Ayat (Khosrow Shojazadeh), suffering from amnesia. After initial hesitation, the villagers allow him to stay—on the condition that he marry a local woman. Ayat chooses Rana, triggering resistance and a series of trials.

Shortly after the wedding, Ayat kills an unknown attacker in the forest during the night. By morning, it becomes clear that the dead man was Rana’s long-missing husband. At the same time, mysterious men dressed in black arrive in the village, issuing warnings before launching an attack. Ayat confronts them and, with Rana’s help, defeats the invaders. Though he saves the village, Ayat senses that the danger has not truly passed—that he is being “called” by something beyond the sea. Wounded, he boards a boat and disappears back into the fog.

The Iranian film is steeped in the art cinema of the 1950s and ’60s, both European and Asian. Contemporary critics often point to echoes of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), particularly in its personification of death, as well as the ritualistic intensity of Sergei Parajanov’s films. The climactic battle in the rain—where cowardly villagers face an external threat—feels like a clear homage to Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954).3

The movie has an episodic structure characteristic of modernist cinema, with meaning emerging through symbolic variation rather than a conventional narrative. Costume and color play a crucial role. Rana begins the film dressed in black, mourning her lost husband. As Ayat enters her life, she wears red and blue scarves. During the final battle, she appears in white. When she loses her second husband as well, she tears off the blood-soaked white robe to reveal black clothing beneath once more. Color here becomes a symbolic shorthand for cycles of death and rebirth.

Roots in Iranian Theater

To view The Stranger and the Fog merely as a collage of international influences would be misleading. The film is equally—and perhaps more profoundly—grounded in Iranian theatrical traditions. Beyzaie was not only a filmmaker but also one of Iran’s most important playwrights and theater directors, as well as the author of the seminal study Theater in Iran (Namayesh dar Iran, 1965), which traces theatrical forms from antiquity to the modern era.

His work draws on a wide range of indigenous performance traditions: the religious passion plays of ta’zieh, the solo mythological storytelling of naqqali, the satirical taqlid plays, and the folk puppet theater kheymeh-shab-bazi. Beyzaie famously fused these local forms with East Asian theatrical traditions, which he also explored in his theoretical writings. His goal was to produce work that spoke to contemporary concerns without losing touch with local culture.4

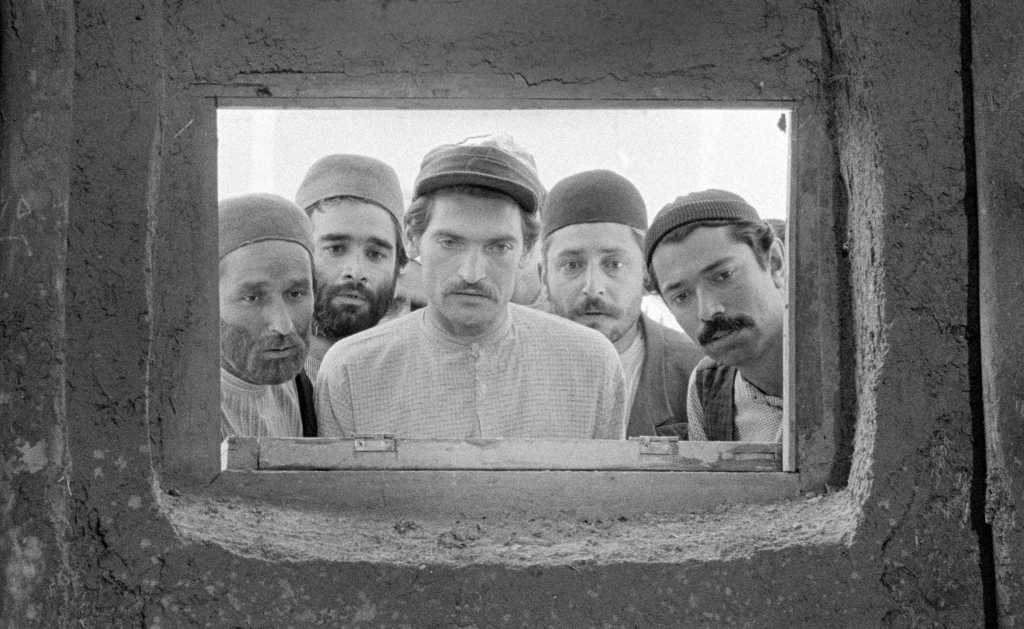

That ethos permeates The Stranger and the Fog. Its theatricality is evident in the declamatory dialogue, the choreographed movement, and the stylized behavior of the characters. The fight scenes are charged with exaggerated, almost highly stylized emotion—gestures more typical of the stage than of naturalistic cinema. In battle, the villagers behave ritualistically: every enemy Ayat subdues is finished off by the villagers, their bodies pushed into the marshes as a sacrificial act meant to ensure the fertility of the land.

The most striking example of stylization comes in the costumes of the mysterious invaders, whose bizarre, almost parody-like “hats” verge on the grotesque. Yet the result is neither filmed theater nor a failed experiment. Instead, Beyzaie achieves an organic fusion of theatrical elements within a medium traditionally associated with realism. His approach relies not only on choreography but also on precise cinematography—careful framing and expressive use of telephoto lenses.

A World Outside of Time

Syncretic by design, The Stranger and the Fog resists clear temporal and spatial classification. Though shot on the Caspian coast of northern Iran, the characters speak standard Tehran Persian rather than local dialects—a notable contrast to Beyzaie’s later Bashu, the Little Stranger (Bashu, gharibe-ye koochak, 1989). Cultural and religious elements are blended freely, alongside motifs invented by the director himself, making the setting feel not tied to any specific region.

The village cemetery features wooden pagan idols with carved faces that stare unsettlingly at visitors, while Christian crosses stand beside individual graves. Explicitly Islamic elements—such as the adhan (call to prayer) and namaz (ritual prayer)—appear only in the second half of the film. The villagers’ ritual mourning for Rana’s husband evokes Shi’a Muharram ceremonies commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Husayn. In Beyzaie’s treatment, however, these rituals evolve into a collective trance reminiscent of the rhythmic movements of Sufi dhikr practices.

Despite its archetypal and ritualistic tone, The Stranger and the Fog is closely connected to the social reality of its time. Like many works of the pre-revolutionar Iranian New Wave and contemporary Persian literature, it deals with fear of the outsider—the unknown other. The film resonates strongly with Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi’s short story collection Fear and Trembling (Tars va larz, 1968). While Beyzaie’s film is set on Iran’s northern coast, Sa’edi’s stories unfold on the southern shores of the Persian Gulf, among fishing communities trapped by poverty, hunger, and pervasive anxiety. In both cases, villagers confront the arrival of strangers from the sea.

Sa’edi treats omnipresent fear and ritualized behavior with the same ironic distance as Beyzaie. Both artists weave together social reality, psychology, and folklore. Fear and trembling are not merely the subjective emotions of fictional characters, but symptoms of a society shaped—and unsettled—by foreign interventions.

Enjoyed my review and analysis? If you’d like to support my blog, you can buy me a coffee or share this article with others who might find it interesting. Thanks for reading!

- https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2023/feature-articles/a-face-in-the-crowd-ritual-mythological-and-political-contexts-in-stranger-and-the-fog-bahram-beiyzaie-1974/ ↩︎

- https://www.film-foundation.org/world-cinema?sortBy=country&sortOrder=1&page=3 ↩︎

- https://reverseshot.org/reviews/entry/3246/stranger_and_the_fog ↩︎

- https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/bahram-bayzais-dramatic-and-cinematic-oeuvre/ ↩︎

Leave a comment