Siamak Etemadi was born in Tehran and moved to Athens in 1995, where he still lives today. He studied film there and later gained professional experience as an assistant director. His short film Cavo d’oro (2012) premiered at the Locarno Film Festival, and his feature debut Pari was screened at the Berlinale in 2020.

The film follows Pari (Melika Foroutan), an Iranian mother searching for her missing son Babak in Athens. Babak emigrated to Greece several years earlier on a student visa, but on the day of his mother’s arrival he does not show up at the airport. Together with her older, emotionally resigned husband Farrokh (Shahbaz Noshir), Pari enters the dark corners of an unfamiliar city. Step by step, they discover that Babak became involved with anarchist groups and disappeared without a trace. The movie captures a painful process of personal liberation and transformation, as the woman in a foreign environment is forced to abandon her illusions and religious certainties.

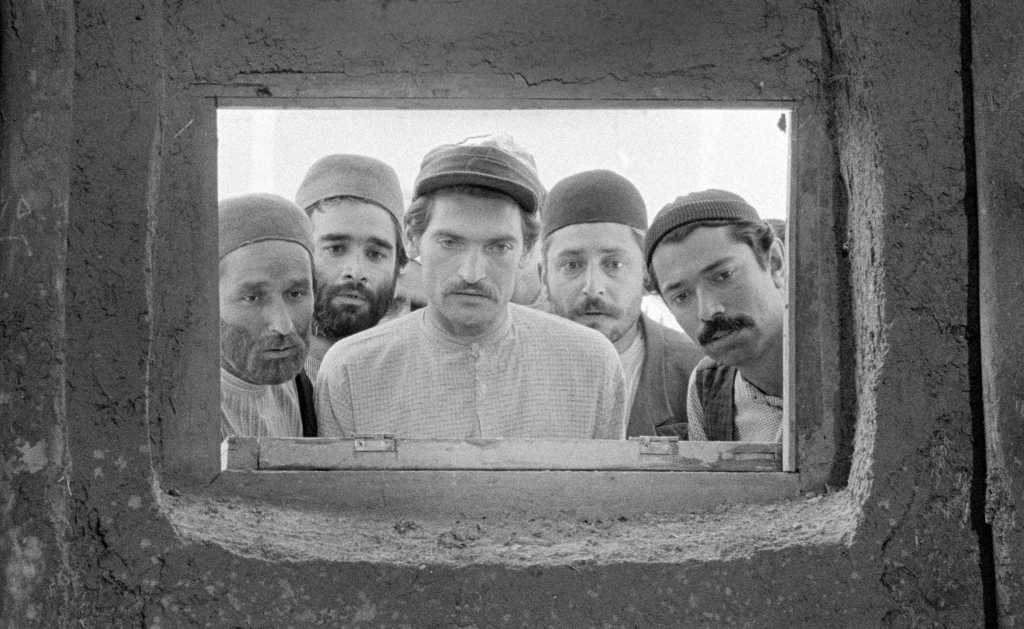

Athens in Pari is far from a tourist paradise. Etemadi places the story in neglected streets filled with drunkards, drug addicts, and the homeless. The action unfolds in poor neighborhoods, crumbling buildings, and brothels. These spaces do not mainly serve as social criticism of a declining Europe. Instead, they form the map of a mythological narrative. The director adjusts the film’s style accordingly—from its intoxicating sound design and expressive camera angles to the use of green and red lighting. In Iranian culture, green is linked to Shia Islam, while red represents the inner fire of love.

Like medieval Persian poetry, the film works through layers of meaning. In the disturbing streets of Athens, Pari faces deep wounds and slowly reaches inner self-knowledge. At the beginning of the film, she appears as a Muslim woman wrapped in a chador; by the end, she is almost indistinguishable from the prostitutes she meets in the port district. Destruction here is not moral decay, but a deep inner rebirth, during which the heroine gradually sheds external religious symbols—from the chador to the headscarf covering her hair.

During their search, Pari and Farrokh find themselves in the middle of an anarchist protest. The hallucinatory scene is soaked in orange light, with fire spreading through the streets and smoke rising from exploding Molotov cocktails. The sense of chaos is intensified by the fact that the Iranian couple has no idea what the Greek anarchists are actually protesting against.

In these authentic-looking sequences, shot with a handheld camera, the film refers to Greece’s long tradition of demonstrations. Etemadi filmed in the Athens district of Exarcheia, long known for clashes between anarchist groups and the police, and some shots were captured during real protests. For viewers familiar with the Iranian context, these scenes may recall protests in Iran, such as the Green Movement of 2009 or the 2019 demonstrations known as Bloody November.

Symbolism in Iranian Cinema: Between Sufism and Zoroastrianism

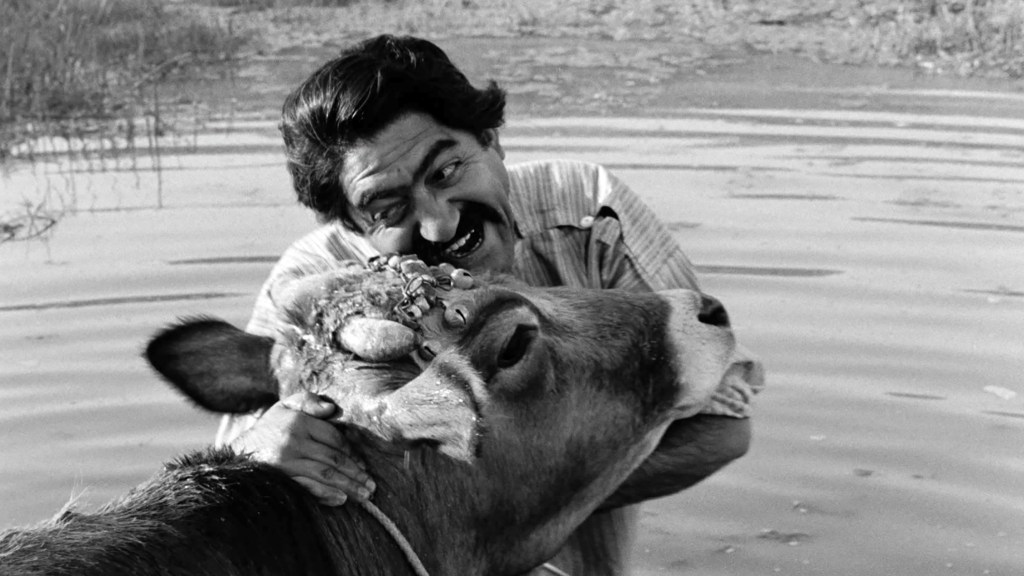

In Pari, the fire lit by the anarchists is not just a realistic background, but a symbol and an archetypal element. Its meaning is developed through verses by the Persian Sufi mystic Rumi. By reading Babak’s notebooks filled with Rumi’s poetry, Pari begins to understand her son’s inner world: “I must burn in order to become fire.” From the conservative Farrokh’s point of view, the lost Babak has morally failed. Yet Babak’s burning does not carry the demonic meaning known from Abrahamic religions. On the contrary, it represents purification from dogma and social conventions.

Even more than to Rumi’s mystical poetry, the film refers to Zoroastrianism, the religion that dominated Iran before Islam. In this ancient tradition, fire is seen as the only element that cannot be polluted; instead, it cleanses everything else. In Zoroastrian rituals, fire acts as a mediator between the human and the divine world.

While Pari goes through an initiatory journey, Farrokh remains a figure of a rigid past, stubbornly clinging to his honor as a man who has completed the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajji). His sudden death is not a fatal blow that would stop Pari’s search for her son. As a mother, she is defined neither by her Islamic identity nor by her husband’s presence. She is a heroine carrying archetypal qualities—the Persian name Pari means “angel” or “fairy.”

Etemadi’s movie feels like a personal statement by an emigrant about the non-dogmatic roots of Iranian culture. Longing for the beloved is a central theme of classical Persian poetry and strongly resonates with the film’s core idea. The loss of the ego and the merging with the beloved are reflected in the process through which Pari sheds her old self in a foreign city and discovers herself more deeply as a mother willing to sacrifice her life for her son. Unlike other films of the Iranian diaspora, such as Tehran Taboo (dir. Ali Soozandeh, 2017) or Holy Spider (dir. Ali Abbasi, 2022), Pari avoids schematic and black-and-white portrayals of its characters.

If you found this article valuable, please consider supporting this blog. Every share or even a small donation helps keep it going.

Leave a comment