This is the second part of a two-part study examining the landmark Iranian New Wave movie The Cow (Gaav, 1969). In the first part, we approached Dariush Mehrjui’s film as a modernist adaptation and compared it with its literary source—the short story by dissident Iranian writer Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi. This second part looks at how The Cow was received at the time of its release and explores the different ways the film has been interpreted.

Thanks to growing international recognition, filmmakers of the Iranian New Wave eventually received state support, yet they continued to represent a dissident form of cinema. The movement’s critical view of contemporary social conditions often clashed with the official vision of the Iranian monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. International film festivals offered an alternative distribution platform for Iranian New Wave films, which were frequently subject to censorship at home.

In Iran, filmmakers were often accused of making “festival films” with no domestic audience, which reduced local distributors’ interest in their work. Ebrahim Golestan had to rent a cinema himself to screen Brick and Mirror (Khesht va Ayeneh, 1964). When Fereydoun Rahnema’s Siavash in Persepolis (Siavash dar Takht-e Jamshid, 1965) was shown in a commercial theater, angry viewers—accustomed to mainstream films full of song and dance—slashed the seat covers with knives in protest.1

Although The Cow was not explicitly political, Mehrjui still faced resistance from censors and an official ban on distribution. The film’s bleak depiction of rural life contradicted the state’s image of Iran as a modern nation of progress and abundance. When the completed print was submitted to the Ministry of Culture and Art, Mehrjui was asked to add an opening title placing the story forty years before Reza Shah Pahlavi’s major reforms. This change was meant to deny the existence of poverty-stricken villages in contemporary Iran. Even after these modifications, the film remained banned for a year.2

A government eager to promote economic growth could not tolerate a vision of a village dependent on a single cow. Nevertheless, a smuggled copy of the film was screened at the Venice International Film Festival in 1971. Although shown without subtitles, the story was so clear and powerful that it required no translation and won the prestigious FIPRESCI Prize. Italian critics, deeply impressed, compared Mehrjui to Pier Paolo Pasolini, Akira Kurosawa, and Satyajit Ray.3 That same year, Ezzatollah Entezami received the Best Actor award at the Chicago International Film Festival for his performance.

This international success prompted the Ministry of Culture and Art to lift the ban and allow The Cow to be screened in Iran. According to film historian Hamid Naficy, most local critics responded positively. One called it “nearly the best Iranian movie,” another “one step from being an extraordinary film,” a third “the birth of the first Iranian film,” and a fourth “an extraordinary leap in cinema.”4 The film’s critical and audience success at home and abroad proved decisive for the future of the Iranian New Wave. Interest in Mehrjui’s work encouraged other filmmakers and producers to pursue alternative, modernist cinema, securing the New Wave’s place in film history.

The Cow as a Political Allegory

In pre-revolutionary Iran of the 1970s, it was common to read works of art politically. Educated audiences expected filmmakers to disguise political commentary in allegorical form. The House Is Black (Khaneh Siah Ast, dir. Forugh Farrokhzad, 1963), a documentary about a leper colony, was initially received in the early 1960s as a humanist appeal for compassion and was viewed favorably by Iranian authorities. However, in the revolutionary 1970s, the same film came to be read politically, with the leper colony interpreted as a metaphor for a pathological society under the autocratic Shah.

The Cow did not escape political interpretation either. In October 1971, Iran held lavish celebrations marking 2,500 years since the founding of the Persian Empire. The goal was to highlight Iran’s ancient civilization while showcasing its modern progress under Pahlavi rule. In reality, these celebrations were widely perceived as an insult. Leaders of major world powers were invited, while the Iranian people themselves were largely excluded.5

Within this context, The Cow was interpreted by Hamid Reza Sadr as a film that “derided the alleged oil boom, the absolute power of the state, and its ritualistic bouts of self-congratulation”6 through its dystopian portrayal of Iranian life. Significantly, in the film about rural life, we never see villagers engaged in agricultural labor. By focusing on neglected social realities, Mehrjui’s film stood in sharp contrast to the Shah’s optimism and vision of progress. As historian Ervand Abrahamian has noted, the Shah’s reforms in fact deepened social inequality. While wealth accumulated at the top of society, rural Iran was left without basic necessities.7

Beyond its depiction of harsh poverty, the film is permeated by an oppressive sense of fear, embodied in the image of an isolated village and the silent gazes of its inhabitants. Sadr interprets the villagers’ fear of the Bolurs—a group of bandit outsiders—as a hint at a potential foreign threat seeking to dominate Iran. This reading is made possible in part by Mehrjui’s decision—compared to Sa’edi’s original story—to render the three bandits more mysterious, opening them up to broader interpretation.

Sadr also draws an analogy between The Cow and Iran’s economy at the time, which was heavily dependent on oil as its primary commodity. Fear of a future without oil mirrored the villagers’ anxiety over losing their only cow. In 1973, Arab states imposed an oil embargo on Western countries. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi responded by doubling oil prices, triggering the “oil shock” that crippled Western economies while dramatically increasing Iran’s oil revenues.

According to Sadr, “the Shah’s constant allusions to oil [his main source of wealth] paralleled the monomania and egocentricity of The Cow’s central protagonist.”8 This interpretation is reinforced by moments of Masht Hassan’s arrogant behavior toward his wife and fellow villagers, whose exaggerated fear of him appears irrational.

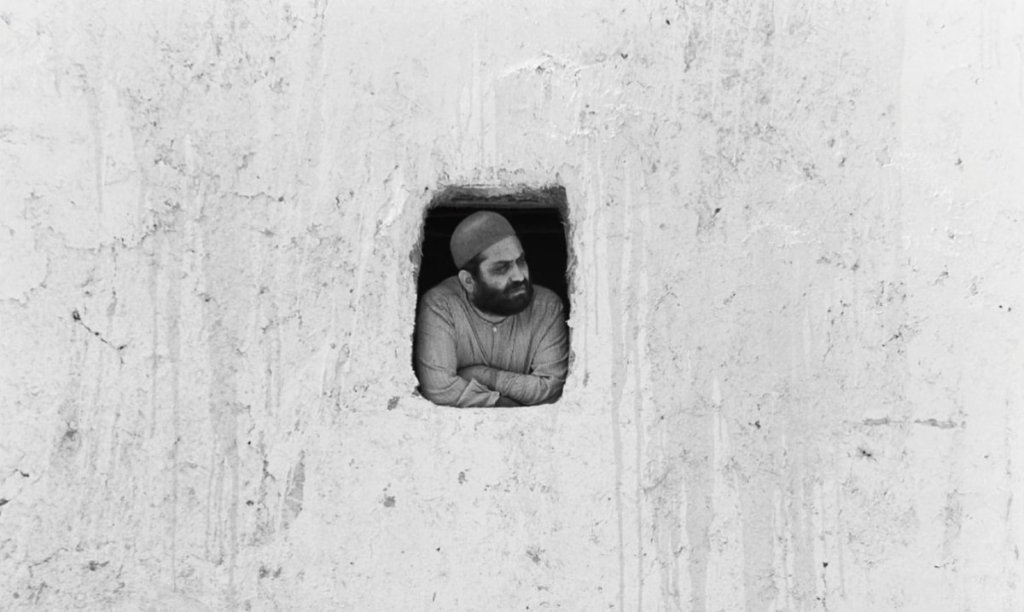

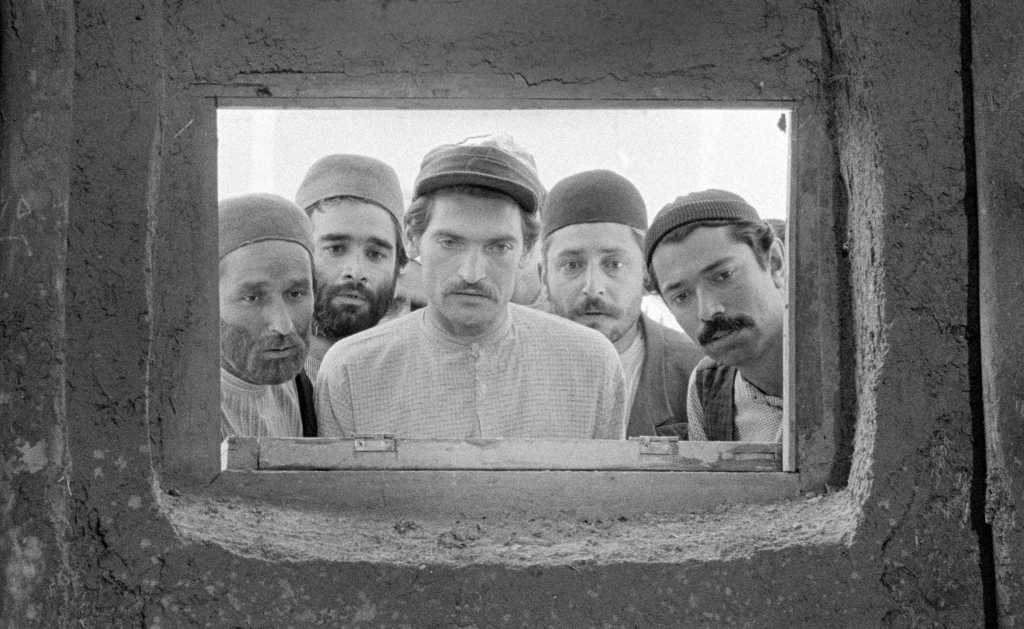

Hamid Naficy adds another layer to this atmosphere of fear by focusing on the motif of voyeurism. Throughout the film, villagers repeatedly watch Masht Hassan from windows, rooftops, and hidden corners. Naficy compares this rural panopticon to the authoritarian climate of the Pahlavi era, when the government was widely feared, particularly because of the notorious security organization SAVAK. Like the omnipresent agents of the regime, the villagers feel compelled to observe and gather information.9

Michelle Langford likewise emphasizes fear as a central theme in The Cow: “Read allegorically, the film seems to suggest that this state of fear has entered the national consciousness making it a prescient marker of the tense sociopolitical climate that would grow to a tumultuous climax over the next decade.”10

The Cow was so influential that its themes of voyeurism and paranoia carried over into other pre-revolutionary Iranian New Wave films, including Bahram Beyzaie’s Downpour (Ragbar, 1972) and Parviz Sayyad’s Dead End (Bonbast, 1977).

Michel Foucault and The Cow: Discipline, Surveillance and Social Control

It is important to note that the political interpretations outlined above emerged several decades after The Cow was completed. Although they are rooted in the social atmosphere of the time, some of their conclusions—such as identifying Masht Hassan with the Shah and the cow with oil—can feel overly constructed or forced.

A more general framework is offered by philosophy, a field Mehrjui also actively engaged with beyond cinema. It is worth mentioning that he translated into Persian, and wrote an extensive introduction to, Herbert Marcuse’s book The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics (1977). In his own introductory essay, The Aesthetics of Reality (Zibashenasi-ye vaqe‘iyat, 1989), Mehrjui articulated his own view on the relationship between art and reality.

When interpreting The Cow, one cannot overlook the work of postmodern thinker Michel Foucault, who was already widely known in the 1960s. Iranian intellectuals living in Paris at the time became familiar with—and inspired by—his leftist ideas. In Madness and Civilization (Folie et Déraison: Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, 1961), Foucault describes the rise of modern institutions as repressive systems that, through segregation and surveillance, suppress everything that deviates from rationally defined normality. It is also worth recalling that Foucault later traveled to Iran in 1978 as a special correspondent for the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, during the Islamic Revolution.

Regardless of whether Mehrjui was directly influenced by this French philosopher, a clear affinity can be seen between the rural community in The Cow and Foucault’s concept of disciplinary power. Masht Hassan’s transformation represents a radical revolt against the village’s “reason.” The villagers do not attempt to understand him; instead, they seek to normalize him.

In this respect, the film develops the themes of madness and discipline more strongly than Sa‘edi’s literary source—most notably through the addition of the physically abused madman, as I discussed in the first part of this study. At the same time, it should be noted that Sa‘edi, who worked professionally as a psychiatrist, may have already sensed this Foucauldian tension between medical authority and human identity while writing the original story.

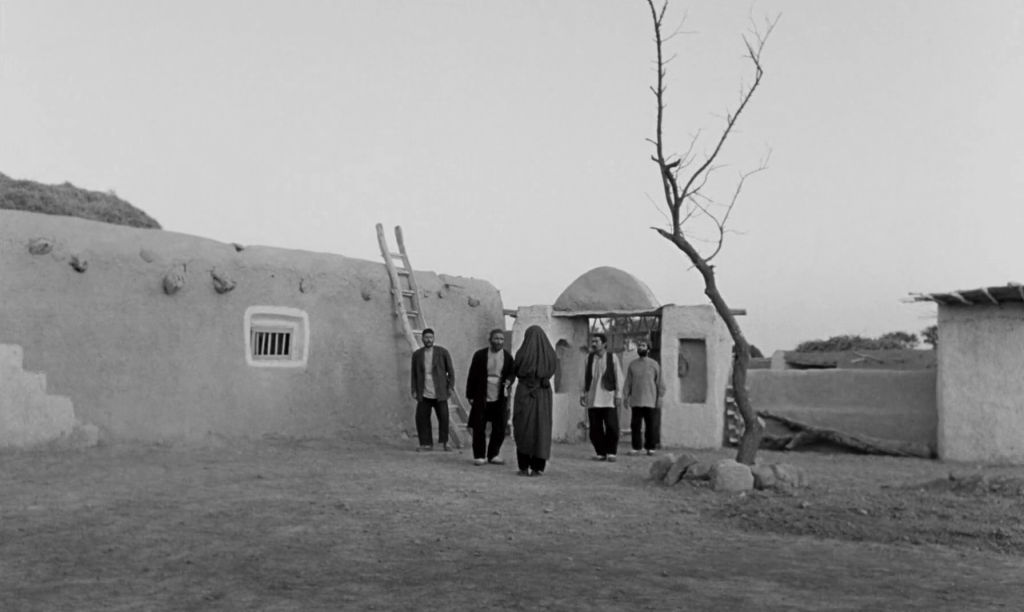

Archetypal Imagery and Sufi Mysticism

Other interpretations move away entirely from political discourse and approach The Cow through ontology or mysticism. These readings are supported by Mehrjui’s sensitivity to rural and natural lyricism. Exterior shots of the stable—later Masht Hassan’s home—are composed in striking juxtaposition with a solitary tree. The sound of blowing wind and wide landscape views lend the film’s harsh realism a subtly mystical tone. A scene in which Masht Hassan sits on the roof of the stable, gazing into the vast landscape, suggests a mysterious form of communication between the human figure and the landscape. From the perspective of nature’s evolving role in Iranian cinema, these moments anticipate the later work of Abbas Kiarostami.

In this spirit, Ali Sheikhmehdi and Yaser Bayat interpret Masht Hassan’s unusual behavior through an archetypal lens. They identify a symbolic concept of home in Mehrjui’s work, set against the destructive transformation of Iran from tradition to modernity. In The Cow, we never see Masht Hassan enter his human dwelling. His true home is the stable—a therapeutic space that heals his inner wounds. According to the authors, “the stable here takes on the meaning of a primal place, that is, the ‘mother’s womb.’”11 The protagonist’s atypical behavior need not be read as senseless madness, but rather as the discovery of an irrational form of bliss.

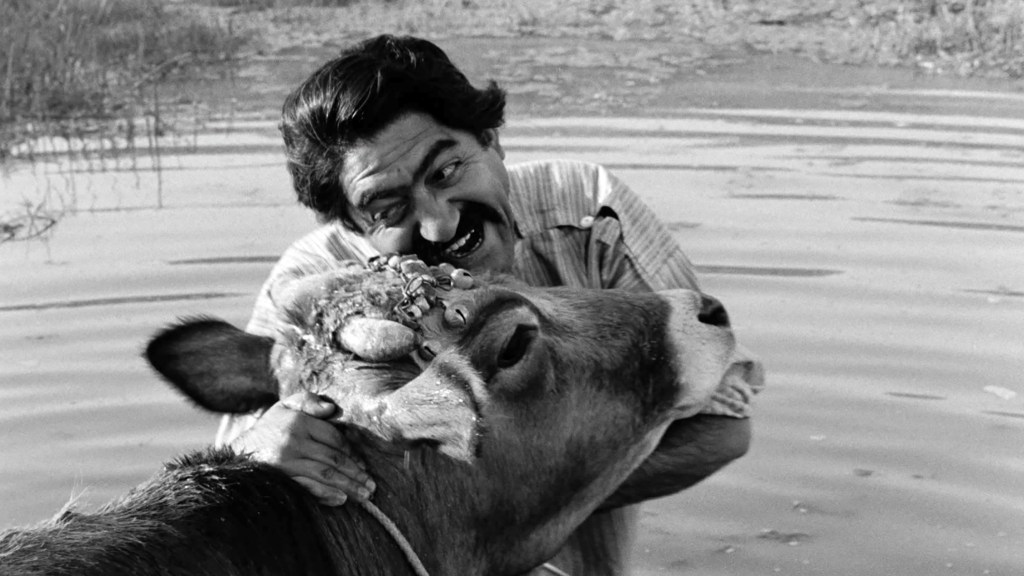

According to Hamid Naficy, Masht Hassan’s identification with the cow can also be understood through the lens of Sufi mysticism, which holds a central place in medieval Persian poetry. Naficy refers to the principle of mystical unity, in which beloved beings merge with one another. As noted in the first part of this study, the film adaptation—unlike its literary source—adds scenes that deepen the bond between human and animal. These intimate moments suggest that Masht Hassan begins to merge with the cow even before her death. This is most evident in the moment when he quietly says to her “Jaanam” (a Persian term meaning “my dear” or “my soul”).

This union culminates in the protagonist’s death, filmed in the same slowed-down visual style used for the cow’s burial. Naficy sees in the relationship between Masht Hassan and the cow an echo of the Sufi longing between two lovers: “If in life the cow and the owner inhabited two bodies, in death they are united spiritually, achieving the highest level of mystic union.”12 Such an interpretation would clearly not be possible without Mehrjui’s specific changes to Sa‘edi’s story and his use of narrative parallelism, as analyzed in the first part of this study.

The theme of rebirth appears once more in the final wedding scene of two young villagers whose gradual closeness we have followed throughout the film. The Cow ends with a shot of Masht Hassan’s wife standing on the roof, gazing into the vast landscape and waiting for her husband—much as he once waited for his cow.

Enjoyed the read? If you’d like to support my work, you can buy me a coffee or share this article with others who might find it interesting. Thanks for reading!

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 347. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 346. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 346. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 347. ↩︎

- Michael Axworthy, Revolutionary Iran: A History of the Islamic Republic, updated ed. (London: Penguin Books, 2023), 77. ↩︎

- Hamid Reza Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 130. ↩︎

- Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 143–146. ↩︎

- Hamid Reza Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 133. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 343–344. ↩︎

- Michelle Langford, Allegory in Iranian Cinema: The Aesthetics of Poetry and Resistance (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 33. ↩︎

- Ali Sheikhmehdi and Yaser Bayat, “Jostari bar hastishenasi-ye mafhum-e namadin-e khane dar filmha-ye Dariush Mehrjui” [An Inquiry into the Ontology of the Symbolic Concept of Home in the Films of Dariush Mehrjui], Nameh-ye Honarha-ye Namayeshi va Musiqi [Journal of Performing Arts and Music], no. 15 (2018), 45. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 340. ↩︎

Leave a comment