Even before the Oscar nominations were announced, In the Shadow of the Cypress (Dar saye-ye sarv, 2023) had already participated in several international film festivals, receiving a number of awards. The creative duo Hossein Molayemi and Shirin Sohani spent more than six years producing this twenty-minute work. The long production time was mostly due to the challenges of hand-drawn animation. Molayemi compares traditional two-dimensional animation to the craft of weaving carpets, considering it a more artistically valuable technique than purely digital production. Free of spoken dialogue, the film crosses national borders and speaks to audiences in a universal language of empathy, pain, and hope.

For Iranian cinema, receiving such a prestigious award no longer comes as a surprise. Feature films from Iran have been successful at international festivals for at least four decades. After Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation (Jodaei-ye Nader az Simin, 2011) and The Salesman (Forooshande, 2016) won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, the award for the animated short brings the third golden statuette to Iranian cinema.

What may be surprising, however, is that this time the honor went to an animated movie. Unlike Iranian feature films, animation has remained more marginal on the international scene—even though some Iranians like to trace the very origins of animation to their land. In Shahr-e Sukhteh, archaeologists discovered a Bronze Age vessel (4th millennium BCE) decorated with successive images of a gazelle in motion. When the vessel is spun, it creates the illusion of the animal leaping—something often described as the world’s earliest known example of animation.1

If we set aside this unique artifact, it is fair to say that Iranian animation does not have a long or deeply rooted tradition. Animators started to gain more visibility only in the 1970s, when the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults supported a group of talented artists, including Farshid Mesghali, Morteza Momayyez, Nafiseh Riahi, Nurreddin Zarrinkelk, Aliakbar Sadeqi, and Parviz Naderi.2 Still, the institute’s animated films never achieved the same international impact as its live-action productions.

The award for In the Shadow of the Cypress has raised hopes among some enthusiasts for a stronger presence and future growth of Iranian animation. Molayemi and Sohani now hope for international support for their planned feature-length project. Such expectations may not be unrealistic. In fact, Iranian art-house cinema went through a rapid transformation in the 1960s and 1970s. Until then, Iranian movie theaters were dominated by dubbed foreign films and domestic popular productions inspired by Indian and Egyptian cinema. The sudden rise of the Iranian New Wave happened without any prior tradition of local art cinema—unlike in France, Germany, or the Soviet Union, where art cinema had roots as early as the silent era.

Still, predicting a real breakthrough for Iranian animation remains uncertain. The success of In the Shadow of the Cypress seems more like an exception than a signal of structural change in the industry—even though just last year another Iranian short, Our Uniform (dir. Yegane Moghaddam, 2023), was nominated for an Oscar in the same category.

A Universal Story: War Trauma and Archetypes

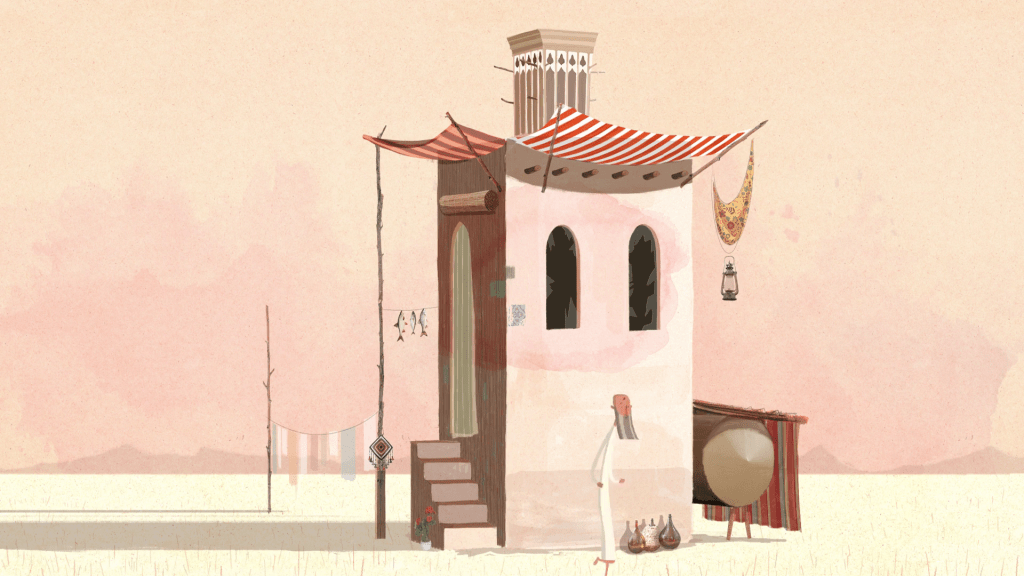

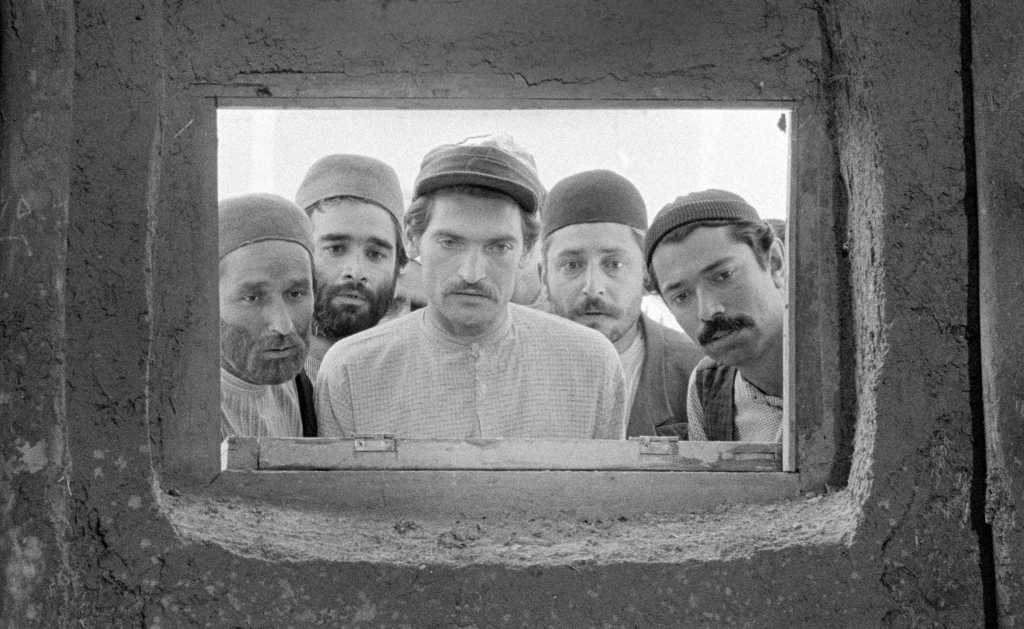

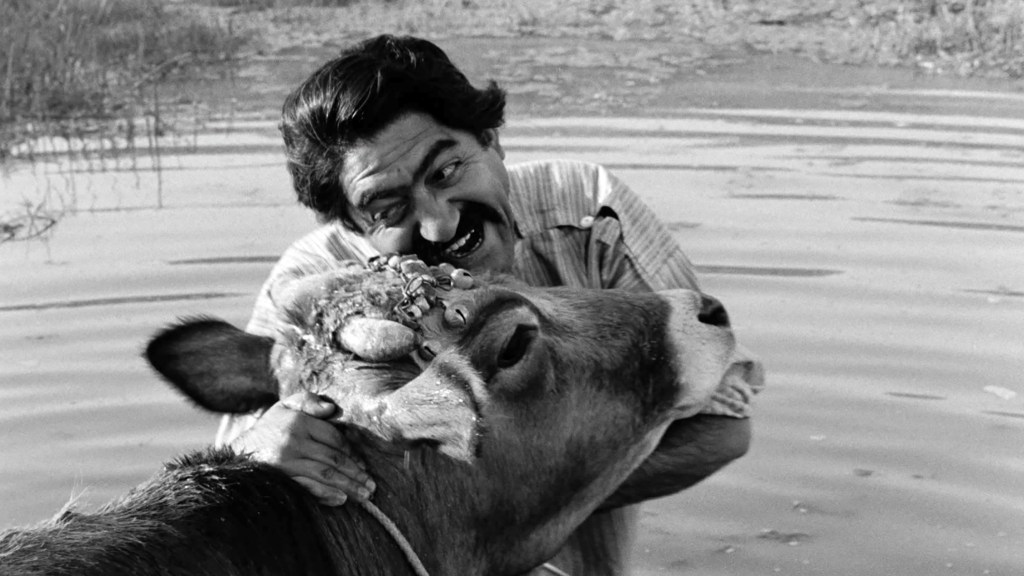

The animated film In the Shadow of the Cypress tells the story of a former captain suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder who lives with his daughter in a remote area by the Persian Gulf in southern Iran. In their modest, isolated house, he tries to lead a quiet life, but painful memories and the psychological wounds of war prevent him from building a devoted and caring relationship with his daughter. Their fragile coexistence is disrupted when a helpless whale gets stranded on the shore.

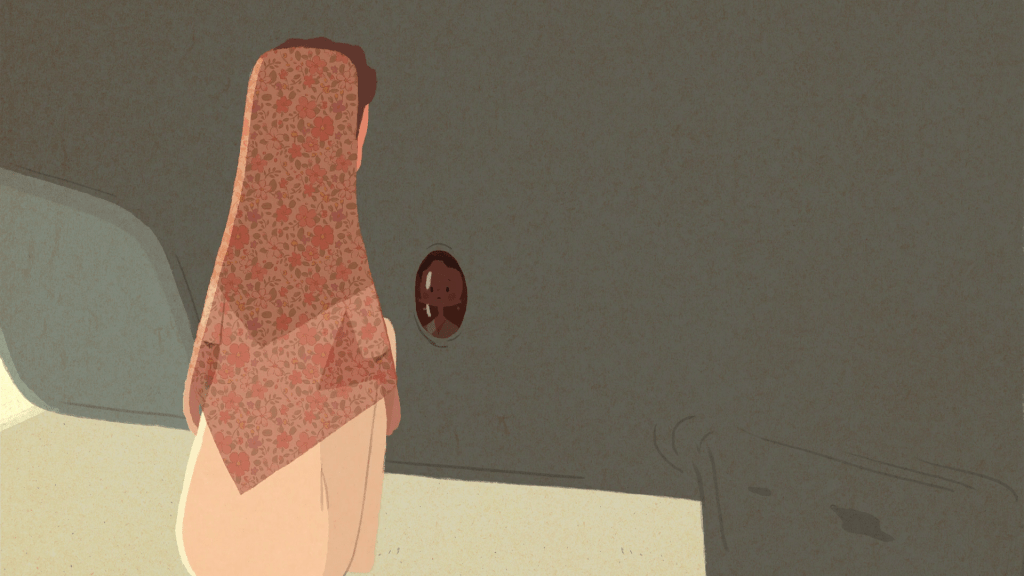

The girl desperately tries to save the animal, while her father, crushed by failure and his own frustration, withdraws further into himself and retreats to his old ship anchored nearby. This event becomes a catalyst that may lead to mutual healing—or deepen the emotional distance between them. The story, simple and almost fable-like, blurs the line between nature and culture. It portrays both human and animal characters with empathy. The viewer is encouraged to sympathize not only with the father and daughter, but also with the whale and even with a small aquarium fish whose life is threatened by the father’s outburst of anger.

The Iran–Iraq war remains a deeply ingrained theme in Iranian society. According to statistics released last year, more than 200,000 Iranian soldiers were killed and over 600,000 were injured during the eight-year conflict. Those who died defending the homeland are honored with the title of shahid (martyr), and their children receive state benefits.

The war has left a strong mark on Iranian literature and film, forming a thematic genre known as defa’-e moqaddas (“sacred defense”). Still, In the Shadow of the Cypress does not quite belong to this category. The filmmakers originally wanted to make a family drama, and the themes of PTSD and wartime memories entered the script only later in development.

After the film’s success, various interpretations of the father–daughter relationship appeared. Iranian psychiatrist and poet Mohammad Reza Sargolzaee, who also works with philosophy and mythology, reads the film through Carl Gustav Jung’s depth psychology.3 He sees in the story the archetypal duality of the masculine principle (animus) and the feminine principle (anima). The traumatized father witnesses his daughter’s compassionate effort to save the whale. Her struggle, filled with empathy, tenderness, and love, embodies the healing force of the feminine principle. The universal archetypal structures Sargolzaee describes, along with the theme of war trauma, resonate across cultures.

Persian Tradition in a New Context

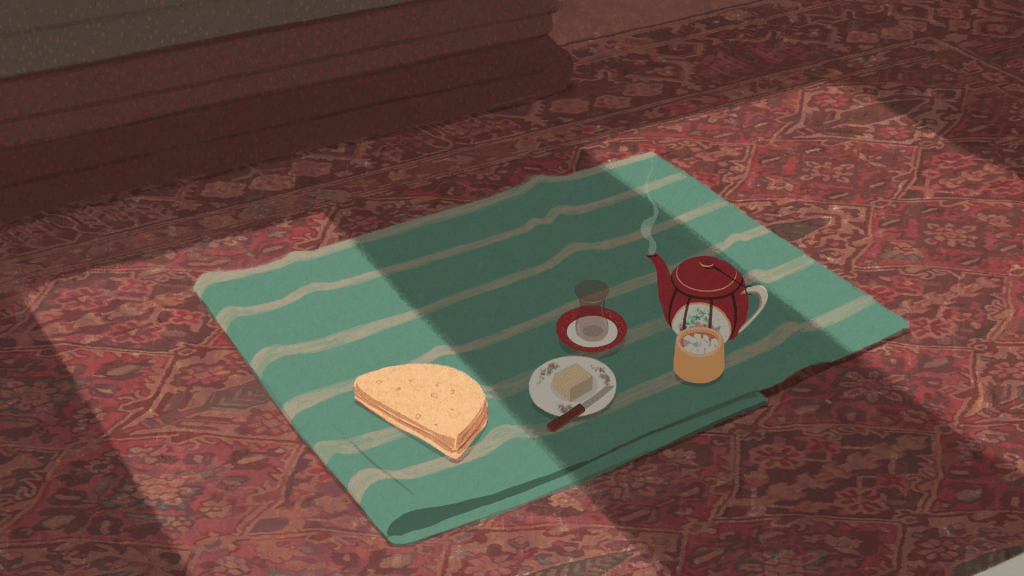

Alongside universal motifs, the Iranian movie also includes elements drawn from Persian tradition and history. These include decorations typical of rural Iran—such as a weaving loom, the livelihood of many villagers, and a traditional breakfast (bread, cheese, tea with sugar cubes) laid out on a sofreh. These cultural details, combined with the use of light and shadow, create a visually striking atmosphere in the interior scenes.

Another inventive touch is the presence of a badgir (windcatcher) rising from the roof of the rural home. This ancient cooling system is traditionally associated with urban palaces and public buildings, and was less commonly used in rural homes. Its presence points back to the deep roots of Iranian civilization, reaching into the pre-Islamic era.

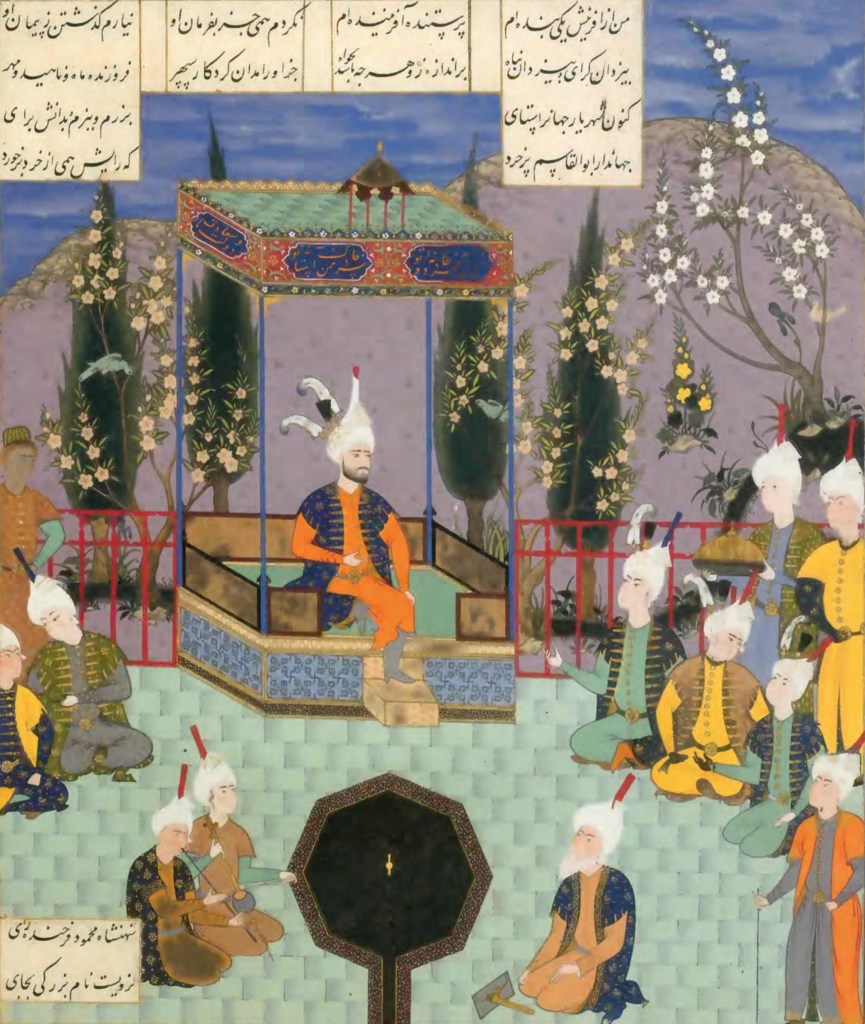

For viewers unfamiliar with Iranian cultural memory, the cypress tree may remain a vague symbol. It appears only in the film’s title, with no explicit explanation in the narrative. The filmmakers seem to assume an audience aware of its cultural significance. In Iranian tradition, the cypress is admired for its beauty and endurance; it survives all four seasons, resists heat and cold, and lives for centuries. In Persian poetry and miniature art, the cypress carries a wide range of meanings: in Ferdowsi’s works it represents freedom,4 in Nizami’s poetry it symbolizes spiritual elevation,5 and in Hafez’s verses it is connected with immortality6 (these are just a few examples).

Yet the film feels closer to twentieth-century modern Persian poetry (she’r-e now), pioneered by poet Nima Yooshij, than to the classical love ghazals or the panegyric qasidas. Free verse in this modern form is not bound by strict rules and more directly reflects contemporary social issues. Molayemi and Sohani were united by their desire to collaborate, and they developed the film’s story through an intuitive creative process—much like modern poets discover their verses. Eventually, they decided to set the story not in Tehran but on the Persian Gulf coast, introducing southern elements and the whale that became the story’s central catalyst.

The filmmakers avoid a literal use of traditional symbols. The father is tall and thin like a cypress, yet he lacks the strength and grandeur the tree represents in classical poetry. The noble meaning of the cypress remains scattered and ambiguous throughout the film, leaving it open to interpretation.

The fragile relationship between the characters is presented with a visual imagination that goes beyond everyday realism. The characters undergo momentary transformations that reflect both vulnerability and mutual inner connectedness. In moments of anxiety, the father’s face turns cold and gray, contrasting with the warm pastel tones that dominate the film.

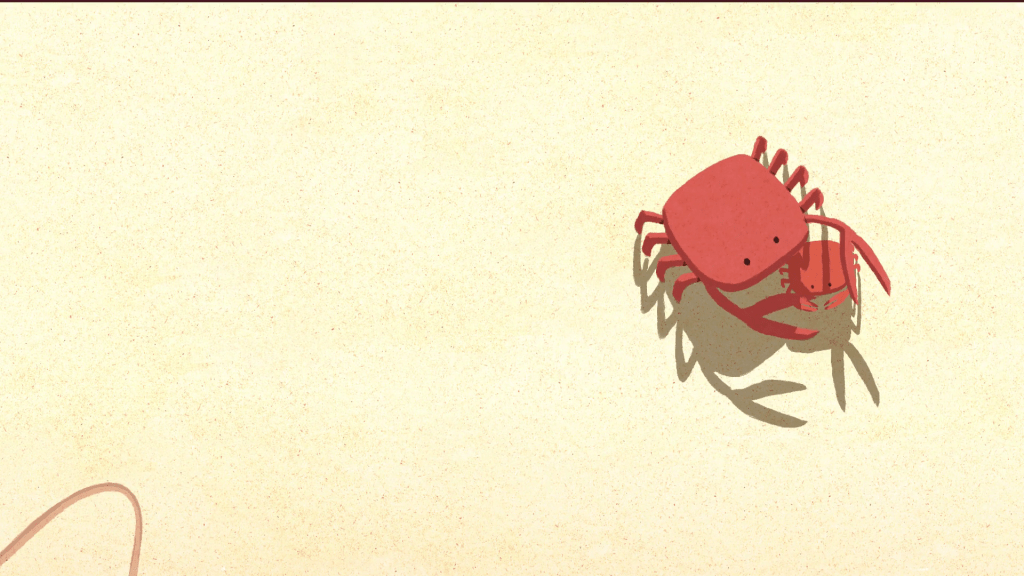

The simple reflection of the daughter’s face in the whale’s eye deepens the emotional connection between human and animal worlds. Equally moving is the parallel between a mother crab instinctively protecting her offspring and the father standing helplessly by his daughter. The filmmakers combine simple storytelling, which gives the viewer access to the characters’ inner lives, with a lyrical style that adds a transcendent dimension.

On both thematic and aesthetic levels, Molayemi and Sohani’s short movie can be seen as an attempt to reconcile modernity with tradition. The tension between these two forces was already central to Iranian literature and cinema before the revolution, and it remains a key framework in the history of Iranian film. In the 1960s and 1970s, modernity—introduced by the Shah’s reforms—was often viewed as a Western import that threatened traditional society. In today’s Iranian social cinema, the situation is almost the opposite, with tradition often being criticized. But In the Shadow of the Cypress avoids this polarized perspective. Instead, it focuses on generational reconciliation and the synthesis of traditional aesthetics with a new artistic form.

If my insight into this Oscar-winning film has inspired you, please consider supporting my work—every cup of coffee helps me continue writing about Iranian cinema. Feel free to share this article with fellow fans of animated cinema. Thank you for being part of this journey!

- Richard Foltz, Iran in World History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 6. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 405. ↩︎

- https://www.bbc.com/persian/articles/cgq9nqwzqzgo ↩︎

- https://ganjoor.net/ferdousi/shahname/manoochehr/sh26 ↩︎

- https://ganjoor.net/nezami/5ganj/7peykar/sh7 ↩︎

- https://ganjoor.net/hafez/ghazal/sh491 ↩︎

Leave a comment