The nonconformist Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad became known for her passionate, rebellious, and philosophical poetry. In the 1960s, as Iran began to open up to Western culture, she emerged as one of the first Iranian women to write openly about love, femininity, and personal feelings. She contributed to Iranian cinema through one of the most remarkable institutional documentaries ever made.

Her filmic elegy of beauty and ugliness, The House Is Black (Khaneh Siah Ast, 1963), combines naturalistic elements with lyrical ones, expressing a humanist ethos through the poetics of extreme cinema. As one of the few Iranian films dealing with disability, it focuses on people suffering from leprosy — specifically, the residents of the Bababaghi colony near the city of Tabriz. Alongside Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (Khesht va Ayeneh, 1964) and Farrokh Ghaffari’s Night of the Hunchback (Shab-e Quzi, 1965), Farrokhzad’s work is considered a key precursor to the Iranian New Wave.

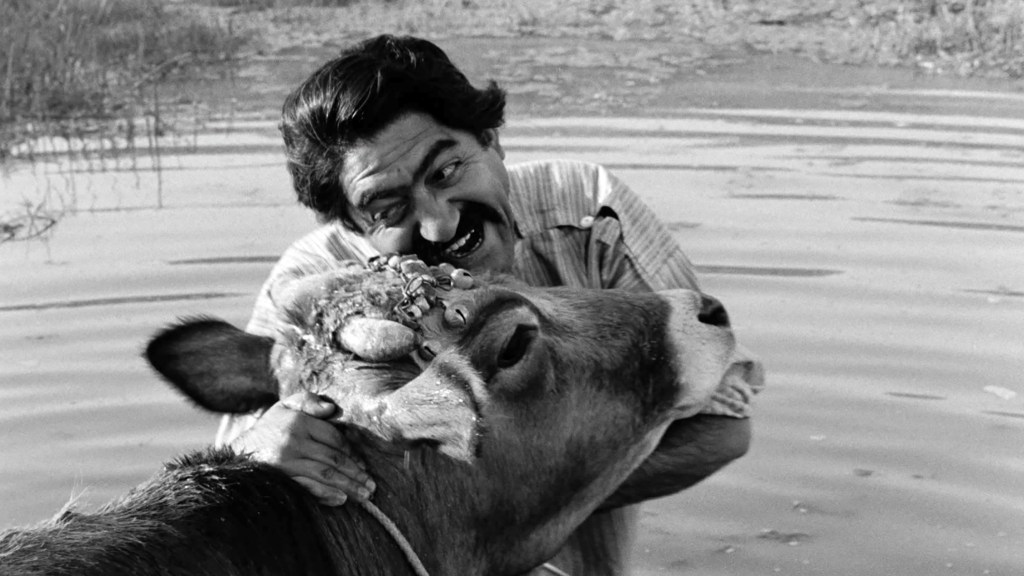

During the making of the film, Farrokhzad gained the unusual trust of the people she portrayed, thanks to her humane and empathetic approach. She formed such a close bond with the leprosy patients that she adopted Hossein Mansouri — the son of two colony residents who was not affected by the disease — and cared for him until her untimely death in 1967.

It’s worth mentioning that The House Is Black was revisited in the context of recent global events in a 2020 article titled “What an Iranian film about a leper colony can teach us about coronavirus,” written by Joobin Bekhrad and published in The Guardian.1 The publication of this article highlights the film’s timeless and universal relevance. As we’ll see below, the film’s ambiguity and depth were already recognized at the time of its release.

How Forugh Farrokhzad and Ebrahim Golestan Shaped Iranian Film History

The House Is Black was produced by a film company founded by Ebrahim Golestan. A versatile creator, Golestan began his career making newsreel films for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Over time, he started recruiting a variety of film enthusiasts — most of whom had no prior filmmaking experience — who shared a strong connection to literature. He trained them himself, building a self-sufficient crew of cinematographers and sound technicians.

The group’s newsreels were far from standard instructional or promotional reports. Instead, their documentary approach was enriched by the unique artistic vision of each filmmaker. This led critics to label their style “poetic realism,” and it helped shape the direction of Iranian art cinema even before the emergence of the New Wave.

Farrokhzad, who was originally hired as a typist, soon moved beyond secretarial duties and took on creative roles in film production. Her professional relationship with Golestan also evolved into a secret romantic affair. The company later sent her to the UK for a short training course on film archiving, where she also edited A Fire (Yek Atash, dir. Golestan, 1961) — a documentary about a seventy-day effort to extinguish a massive oil well fire near Ahvaz.

Farrokhzad also made a brief appearance as an actress in Golestan’s first feature film, Brick and Mirror. She played a woman in a chador who, in the opening scene, leaves a baby in a taxi — setting the main plot in motion. Some film historians don’t associate Farrokhzad primarily with her own directorial work, but rather with Abbas Kiarostami’s later film The Wind Will Carry Us (Bad Ma Ra Khahad Bord, 1999), whose title quotes one of her poems.

The twenty-two-minute The House Is Black remains Farrokhzad’s only film as a director. Although the film was commissioned by the Society for the Aid of Lepers (Jam’iyat-e Komak be Jazamiyan), it was far from a typical institutional documentary — it didn’t promote or praise the sponsoring organization. The poet-director’s creative freedom was made possible by mixed funding. The commissioner had only limited resources, so a large part of the budget had to be covered by Golestan.2 This dual sponsorship gave the filmmakers enough freedom to create a work that was distinctive both in content and style.

Balancing Raw Realism and Lyricism

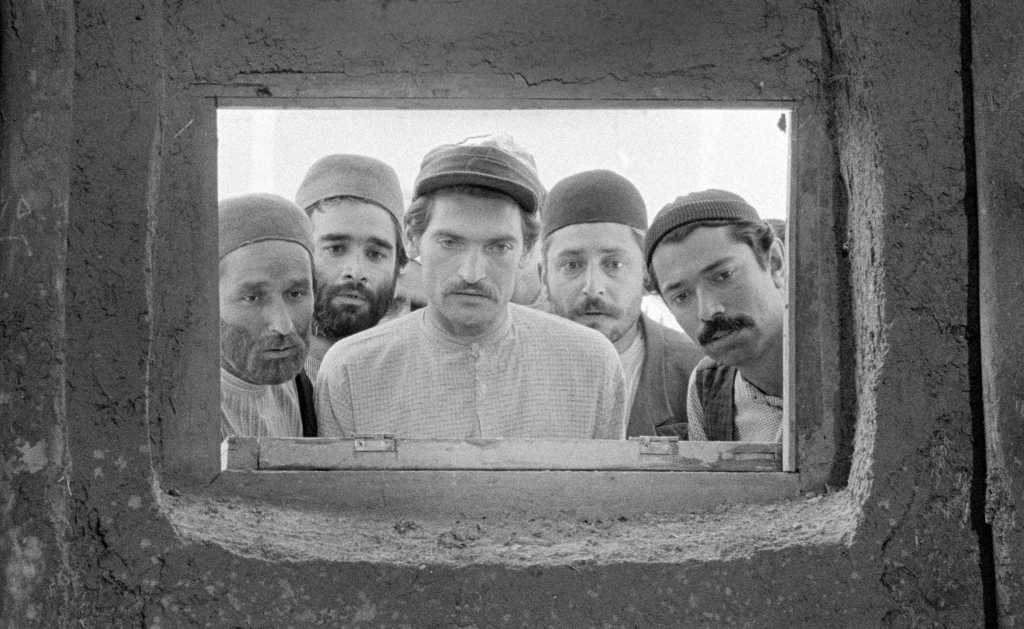

The House Is Black falls into the category of extreme cinema mainly due to its direct, naturalistic portrayal of the physical deformities of leprosy and the suffering of the people living in the Bababaghi colony. Farrokhzad does not shy away from showing the harsh reality of the disease — instead, she confronts it directly and without embellishment, forcing viewers to face pain and physical “ugliness” in its rawest form.

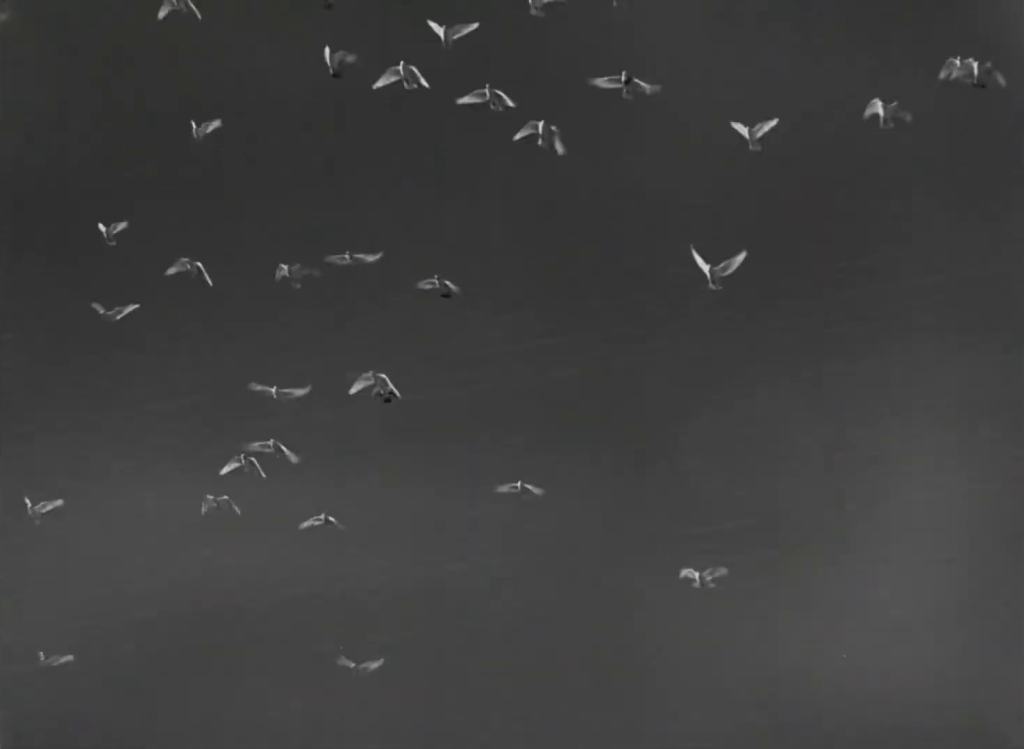

The people affected by leprosy are mostly shown engaged in everyday activities such as sitting idly, eating, or playing ball games. Shots of a calm pond or birds in flight serve as visual symbols of escape from bodily suffering and highlight the filmmaker’s poetic sensibility. These mundane scenes are complemented by wedding celebration and images of women breastfeeding. These life-affirming moments contrast with the surrounding suffering, yet within the context of a pervasive infectious disease, they avoid falling into superficial optimism.

The layering of meaning is achieved through a voiceover narration by Golestan and, more importantly, Farrokhzad herself. In a reflective philosophical poem, the poetess recites verses filled with despair and rebellion against painful existence:

Our existence is like a cage full of birds,

filled with the cries of captivity.

The film also includes quotations from the Bible and the Quran. The recitations of religious verses create thematic parallels with scenes set in a mosque. In the context of such intense images of suffering, religion appears as a rare — though not entirely convincing — source of consolation.

Golestan’s voice appears only briefly in the film, serving as a counterpoint to the female empathy that dominates. While narrating scenes in the clinic, he outlines the symptoms of the disease. His male voiceover represents the voice of science, which, in contrast to Farrokhzad’s poetic narration, feels secondary. At the same time, his socially critical remark — “Leprosy appears where there is poverty” — exposes the failures of the healthcare system. This statement foreshadows the socially conscious themes that would define the Iranian New Wave cinema in the late 1960s and 1970s, particularly in films such as The Cycle (Dayereh-ye Mina, dir. Dariush Mehrjui, 1975) and The Sealed Soil (Khak-e Sar be Mohr, dir. Marva Nabili, 1977).

Farrokhzad’s contribution to Iranian cinema lies in her radical cinematic expression, which moves away from objective observation of everyday life. Instead, she reshapes reality into new rhythmic relationships, infusing naturalistic material with poetic quality. Long takes are interwoven with short, fragmented images of deformed bodies; moving camera shots alternate with static compositions. Several identical shots are repeated throughout the film in varying forms, creating a kind of visual verse structure.

Some aesthetic and calming motifs offer slight relief from the bodily horror. Among them are floral ornaments, which serve as a poetic complement to the disfigured face of a woman gazing into a mirror at her own “ugly beauty.” Through this synthesis of beauty and ugliness, the poet teaches us to perceive harmony between opposing elements. In doing so, the film opens space for a deeper understanding of human dignity — one that transcends physical appearance and bodily pain. It also helps the viewer accept suffering not only as a source of fear, but as part of the complex human experience.

Interpreting The House Is Black: Existentialism and Spiritual Transcendence

When The House Is Black premiered in Tehran, it was mostly met with praise from critics and was seen as a powerful call for empathy toward people affected by leprosy. According to Empress Farah Pahlavi, the patron of the Society for the Aid of Lepers, the film helped positively shape public opinion about the disease.3 In 1963, the film received the main award at the International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen.

The film was often compared to Land Without Bread (Las Hurdes: Tierra sin pan, dir. Luis Buñuel, 1933), including by filmmaker Chris Marker. In his documentary, Buñuel depicted poverty and degenerative illness in a remote and underdeveloped region of Spain. His film was banned by the Spanish government at the time for portraying the country in a negative light. Farrokhzad, on the other hand, managed to avoid censorship by the Shah’s regime and even gained positive attention from Iranian authorities.

However, the film also faced harsh criticism. Film critic Shamim Bahar called The House Is Black completely dishonest.4 He felt deceived after watching it. Bahar criticized the film for lacking concrete information about how the leprosy colony functioned or how the patients interacted with the outside world. He also dismissed Farrokhzad’s use of associative editing, which he found senseless and disjointed.

Bahar’s rejection of the film was largely due to an inadequate critical framework — he expected a conventional documentary, not a bold modernist work. At that time, unlike France, Germany, or the Soviet Union, Iran lacked a strong tradition of art cinema, which might have prepared audiences for such a radical piece. Farrokhzad deliberately avoided ethnographic description and didactic storytelling. This allowed her to explore philosophical and existential themes, as well as the tension between ugliness and beauty, through her unique artistic lens.

The film’s openness and complexity later led to politically charged interpretations. In the turbulent pre-revolutionary climate of the 1970s, films in Iran were often read symbolically or politically — whether or not the filmmakers intended them that way. During this period, the film’s extreme naturalism lost some of its original humanist meaning. The isolated leper colony came to be seen as an allegory for a diseased Iranian society under the autocratic rule of the Shah.

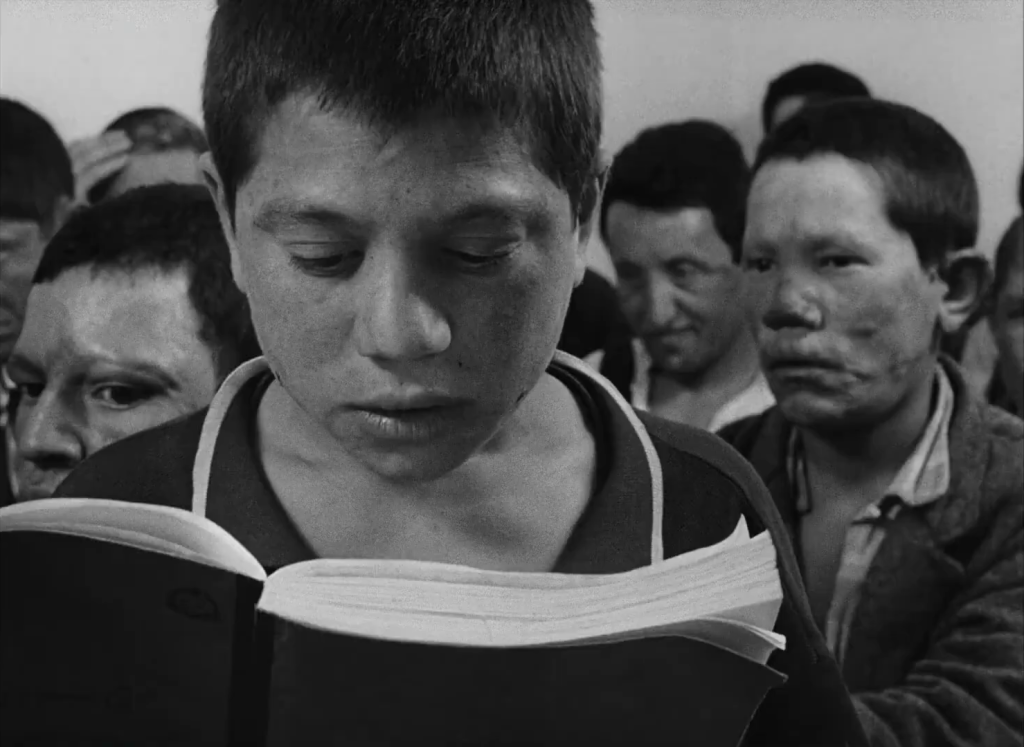

The film’s complexity is further reflected in the way it can be interpreted both as a critique of religion and as a spiritually charged work. An ironic tone emerges in an early scene where children thank God for their hands, ears, or legs — even when those limbs are deformed or entirely missing. The scene is echoed at the end of the film, when a teacher asks a student to name something repulsive, and the child answers: “a hand, a leg, a head.”

In contrast, the film’s closing moments shift from despair to mystical transcendence. When the student is asked to write a sentence using the word “house,” he recalls the sign above the entrance to the leper colony: “House of the Lepers.” The phrase he ultimately writes — “The house is black” — mirrors the overwhelming sense of agony. Just above these desperate words, another phrase remains on the blackboard: “Rain, rain.” In the final voiceover, Farrokhzad reads in a sorrowful tone:

And you, Oh full-flowing river,

driven by the breath of your love,

come to us,

come to us.

The film ends with this Sufi moment. The seemingly random combination of unrelated elements suggests a hidden mystical order. The image of a dark house, flooded by a symbolic rain of love — created through the quoted lines of the poem and the child’s chalk writing — carries unexpected transcendent power. In its final frame, the film becomes a meditation on hope, born even in the deepest darkness.

Enjoyed the read? If you’d like to support my work, you can buy me a coffee or share this article with others who might find it interesting. Thanks for reading!

- https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/apr/06/house-is-black-iranian-documentary-leper-colony-coronavirus ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 87. ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 87–88. ↩︎

- Shamim Bahar, “Pezhvak – Khaneh Siyah Ast,” Andishe va Honar 4, no. 8 (Mehr 1342 [1963]). ↩︎

Leave a comment