This is the second of two parts exploring Abbas Kiarostami’s unique form of eco-criticism in cinema. In the first part, we examined his poetic relationship with nature, shaped by Persian poetry and his artistic background. We traced his cinematic journey through Iranian cinema, from socially engaged neo-realism to contemplative poetic realism. The director’s work highlights a respectful approach to depicting natural landscapes and marks a significant contribution to the development of Iranian art cinema.

Beauty as a Path to Life: Awakening in Iranian Slow Cinema

Kiarostami’s observation of the Iranian landscape goes beyond mere aesthetic exercise; it also serves a therapeutic purpose. The filmmaker guides both the characters and the viewers to realize that the everyday world is beautiful and therefore good for life. In Kiarostami’s thinking, the boundary between ethics and aesthetics, eco-criticism and humanism, becomes blurred. This perspective on life (and also on death) is characteristic of his work throughout the 1990s. It also reflects deeper currents within Iranian culture, where poetry, nature, and spirituality have long been intertwined.

And Life Goes On (Zendegi va digar hich, 1992) explores the aftermath of an earthquake in the region where Kiarostami filmed Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khane-ye dust kojast?, 1987). When one of the drivers asks, “What sin has this nation committed that God punished it like this?”, he assumes the disaster is a consequence of human wrongdoing. For the elderly Mr. Roohi, however, the earthquake is not God’s punishment but “a hungry wolf that attacked a flock of sheep—some it devoured, others it spared.” Roohi understands the disaster more as a result of natural forces than divine will. According to him, the tragedy deepens people’s appreciation of life.

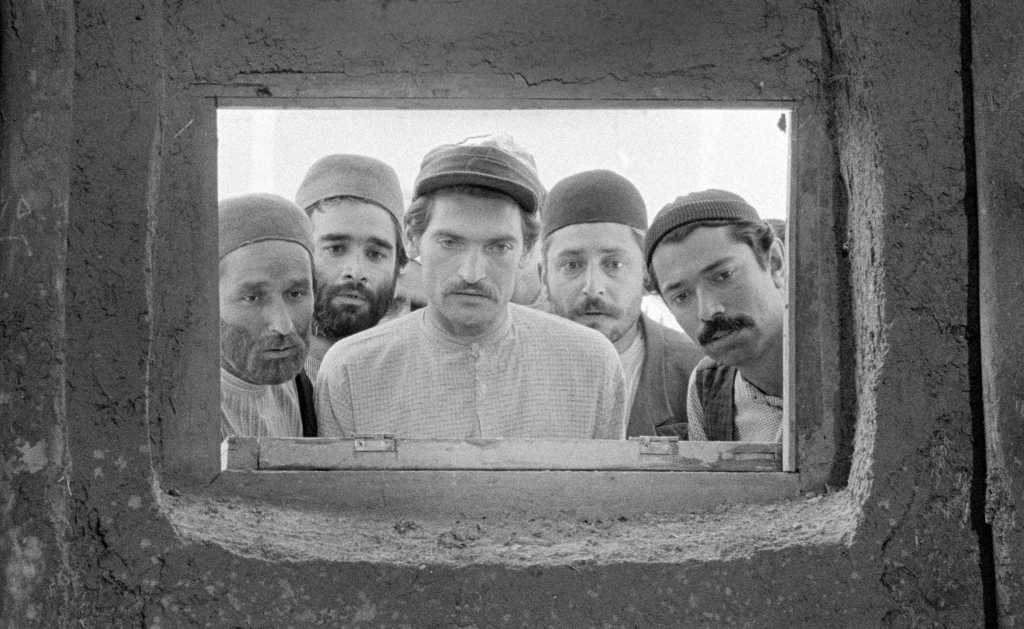

Rather than focusing on death and suffering, Kiarostami shifts our attention to the resilience of life. He doesn’t portray destruction as a final state, but as a gateway to renewal. The Iranian filmmaker uses the ruins of buildings as frames through which he focuses on natural beauty. The mystery of life thus becomes his primary subject.

Kiarostami expresses reasons to live through natural motifs in other films as well. The barren environment of the slow cinema classic Taste of Cherry (Ta’m-e gilas, 1997) reflects the inner emptiness of the protagonist Badii, who has turned away from society and decided to commit suicide. He drives through the barren landscape, searching for someone to assist him in his plan. The third person he approaches is an older Turk named Bagheri, who agrees to help, but first tries to dissuade the despairing man from suicide. He takes Badii on a new path, different from the dry land, saying that although it’s longer, it’s also more beautiful. With the arrival of this „old sage“, the story shifts its focus to trees, birdsong, and small signs of life.

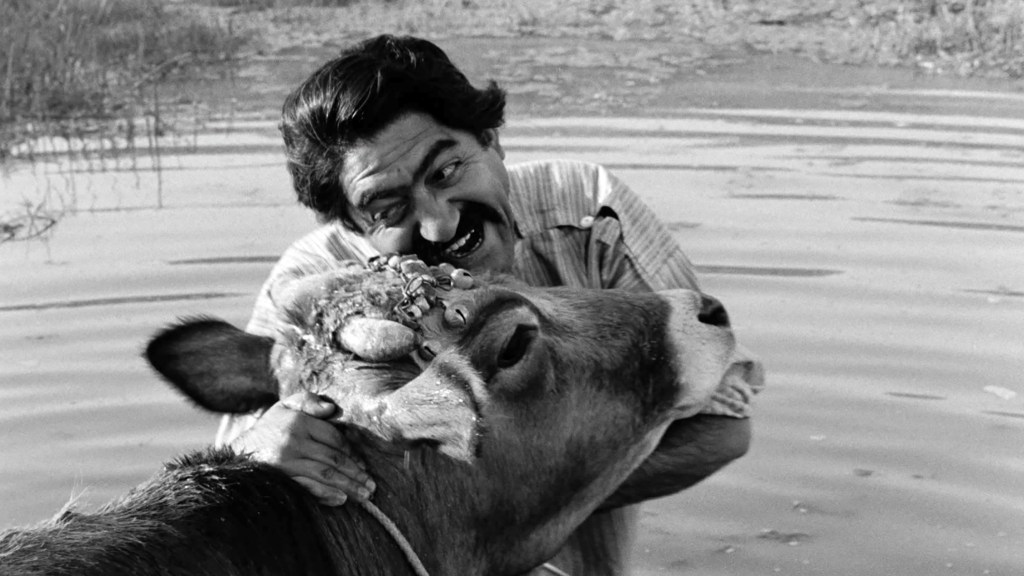

Bagheri recounts how he once wanted to commit suicide but was saved by the taste of mulberries growing on the tree from which he had planned to hang himself. The taste of these fruits, the sunrise, the full moon, and the starry sky are, for him, reasons to live. Bagheri speaks about the meaning of life and communicates the inexpressible to Badii by taking him on a different, more beautiful path. In doing so, he attempts to reframe Badii’s thinking from pain to an appreciation of the everyday world.

In The Wind Will Carry Us (Bad ma ra khahad bord, 1999), a notable film within Iranian cinema, the educated Tehran resident Behzad arrives in a village to document a funeral ritual. His interest in death does not arise from a search for deeper meaning but treats it as an emotionally detached subject of study. He impatiently awaits the passing of an elderly woman because the funeral ceremony will provide material for an interesting report. The character of the older doctor echoes Mr. Roohi and Bagheri from previous films. According to the doctor, death is the worst illness: “When you close your eyes to this world—its beauty, the wonders of nature, and God’s generosity—it means you will never return.”

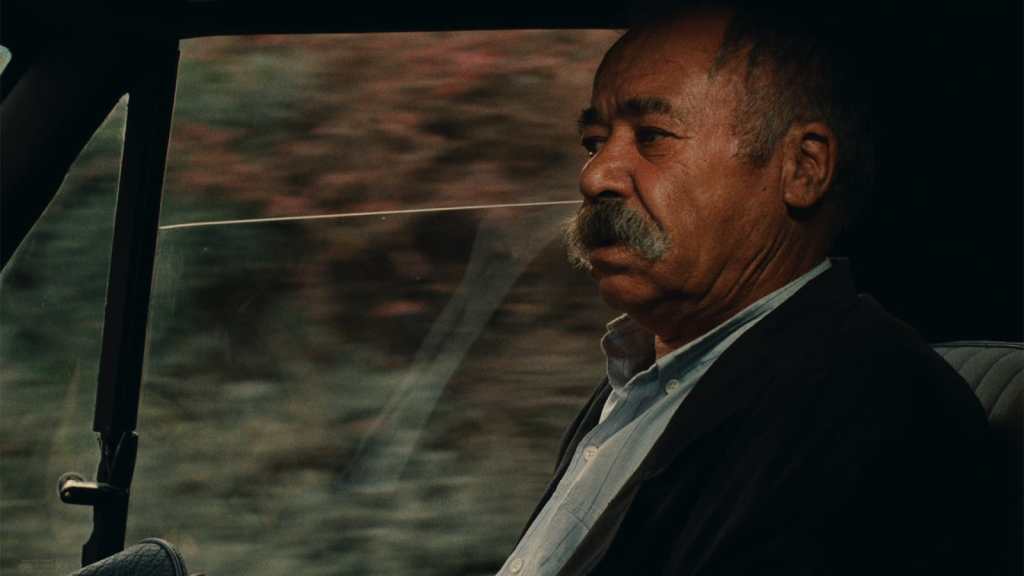

While the doctor rides a motorcycle, allowing him to fully perceive the beauty around him, Behzad remains confined in his car, his view of the world filtered through a dirty windshield. Instead of noticing the life around him, he fixates on death and impatiently awaits its arrival. In anger, he overturns a turtle on its shell, but without his knowledge, the turtle independently rights itself after a moment and continues on its way.

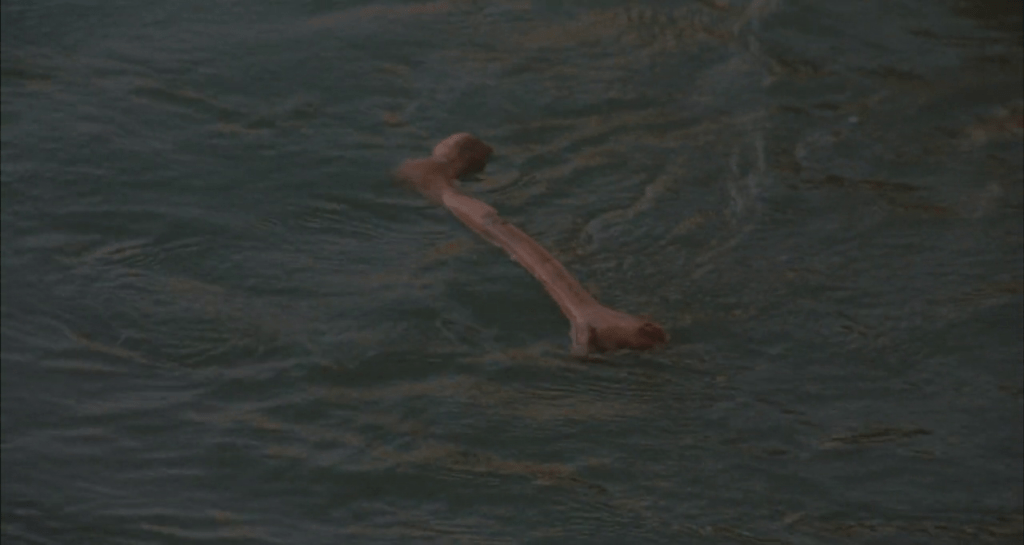

The film’s ending can be interpreted as a chance for Behzad’s inner transformation: he throws away the bone he had obsessively kept in his car—a symbol of his fixation on death—and cleans the windshield. He now finds a new way to see the world, freed from selfish motives.

Although Kiarostami’s characters speak about the pleasure of tasting fruit and the beauty of the world, the actual acts of eating or other sensual pleasures are never shown directly. By doing so, the Iranian filmmaker shifts attention away from sensuality, transforming pleasure into a deeper and more mysterious phenomenon. The experiences offered by Kiarostami’s observational aesthetics arise from a disinterested appreciation of nature, rather than from possession or consumption. Just as the Persian poet Hafez invites us to embrace life through his verses, Kiarostami highlights the world’s beauty in his films to counter inner emptiness and guide his audience toward a mindful awareness of the ever-present life around us.

When Nature Teaches Us to Dwell

In the 1980s and 1990s, the settings of Kiarostami’s films shift from urban environments to the countryside. The only exception is the film Close-up (Nema-ye nazdik, 1990), which takes place in Tehran. During this period, the Iranian film director employs a narrative structure in which a running child or a passing vehicle seamlessly moves between the natural landscape and the village. These transitions highlight the visual harmony between natural and built environments, blurring the boundary between the two worlds—at least on an aesthetic level.

The rural buildings, which respect the natural features of the environment, stand in stark contrast to the modernist trends of urban architecture. For this reason, the urban visitors in The Wind Will Carry Us describe the Kurdish village as a “well-hidden place.” The shapes of the houses and their arrangement appear as random as the landscape’s natural relief. Narrow, winding streets and various nooks create a cozy living space. The earthen color of the buildings harmonizes with the surrounding soil — the village, situated on a slope, becomes a “miniature” version of the mountainous terrain.

The camera often captures the village and its inhabitants from a high vantage point, just as it does the landscape. Kiarostami views both nature and human society as a unified whole. Alongside Persians, he portrays characters from various ethnicities, social classes, and professions. In Taste of Cherry, Badii meets three men: a Kurd (a soldier), an Afghan (a theology student), and a Turk (an ordinary man). Their conversations touch on themes related to the wartime suffering experienced by each group. In The Wind Will Carry Us, set in a Kurdish village, the dialogues mix the Persian language of the urban characters with the Kurdish spoken by the locals.

It is clear that by moving to natural settings, Kiarostami does not lose interest in people — the focus of his early films from the 1970s. Just as he seeks to observe and gently portray the landscape, he also approaches human society with a similarly holistic sensibility. A symbiosis emerges between culture and nature: poetry shapes his view of the natural world, while his perception of human society is enriched by his experience of the landscape.

The Iranian film director does not offer viewers pragmatic reasons to protect the environment. Kiarostami’s eco-criticism is rooted primarily in aesthetics, deeply influenced by Persian poetry. By engaging with his artistic works, viewers can cultivate a deeper connection to everyday nature, learning to perceive it with greater mindfulness and sensitivity. This reframing of thought can ultimately awaken a sense of care for the beauty of nature — and for the value of life itself.

If my insight into Kiarostami’s eco-criticism in cinema has inspired you, please consider supporting my work — every cup of coffee helps me continue researching and writing about Iranian cinema. Feel free to share the article with others who appreciate slow cinema and the beauty of our world. Thank you for being part of this journey!

Leave a comment