What does it mean to view nature through the lens of a cinematic poet? How can slow cinema help us see nature more mindfully and with renewed sensitivity? This is the first of a two-part exploration of Abbas Kiarostami’s unique approach to eco-criticism in cinema.

At the beginning of Kiarostami’s film The Wind Will Carry Us (Bad ma ra khahad bord, 1999), a group of people drives along a winding road, searching for a solitary tree to use as a landmark in an unfamiliar landscape. One of them casually quotes a verse from a poem by Sohrab Sepehri:

Before you reach the tree,

there is a garden alley

greener than God’s dream.

The same poem, rich in mystical imagery of nature, is also referenced in the title of another of Kiarostami’s films, Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khane-ye dust kojast?, 1987). Often called a cinematic poet, Kiarostami draws on the tradition of Persian poetry in his aesthetic portrayal of nature.

Kiarostami held Sepehri in particularly high regard. The poet created his work during the turbulent decade before the Islamic Revolution in Iran (1979). While some of his contemporaries engaged in politically committed literary movements, Sepehri’s work—deeply inspired by the mysticism of East Asia and India—remained apolitical. Similarly, Kiarostami, in his peak period, preferred contemplative observation of everyday landscapes and life over explicitly political themes. Among other things, his visual style closely echoed Sepehri’s painterly approach.

Kiarostami’s poetic connection to nature is evident not only in his films but also in his poetry. His haikus suggest a move away from anthropocentrism:

I sold my garden. Today. Do the trees know? ----- For some, the summit is a place to conquer! For the summit, a place of snow.

The Iranian filmmaker was so fascinated by trees that he often used them in interviews as metaphors for himself or for humans in general. He explained his decision to remain in Iran with the following metaphor: “If you take a tree that is rooted in the ground and move it from one place to another, it stops bearing fruit. And if it doesn’t stop, the fruit won’t be as good as it was in the original place. If I left my country, I would be like that tree.”

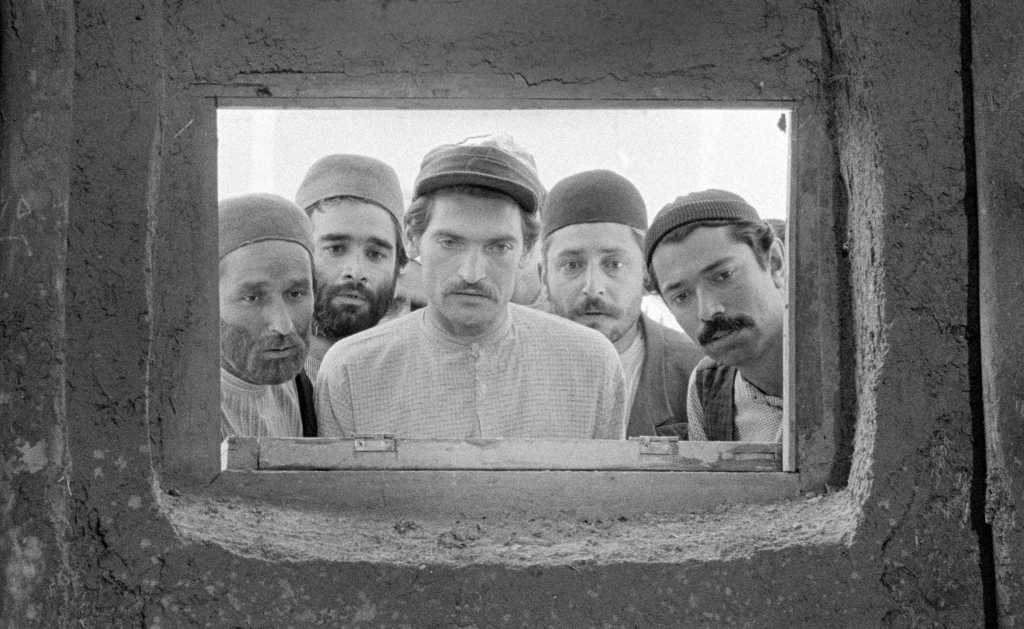

Although Kiarostami enjoyed solitude, he never lost compassion for humankind. His philosophical perspective changed over the decades—he emphasized different themes at different times but never stopped being a humanist. Generally speaking, in his early “neo-realist” period (the pre-revolutionary 1970s), he used a documentary style focusing on a suffering child amidst a neglected urban society. In his middle and peak “poetic realism” period (the 1980s and 1990s), he shifted attention to contemplation of natural beauty and reflections on life and death. In his late period (after 2000), female protagonists came to the forefront.

This shift from an initially socially critical cinema to later contemplative works also marks a move from urban to rural settings. Bahman Magsudlu, the director of a documentary about Kiarostami, describes it like this: “The photographs he took, besides showing his perspective and interest in nature and the environment, reveal that he was tired of the aggressive city environment. He loved nature and the environment. One of his unique qualities was that he dealt with various dimensions of a human, a tree, a branch, a flower, or a plant, and even a piece of wood, to show different aspects of the tree.”

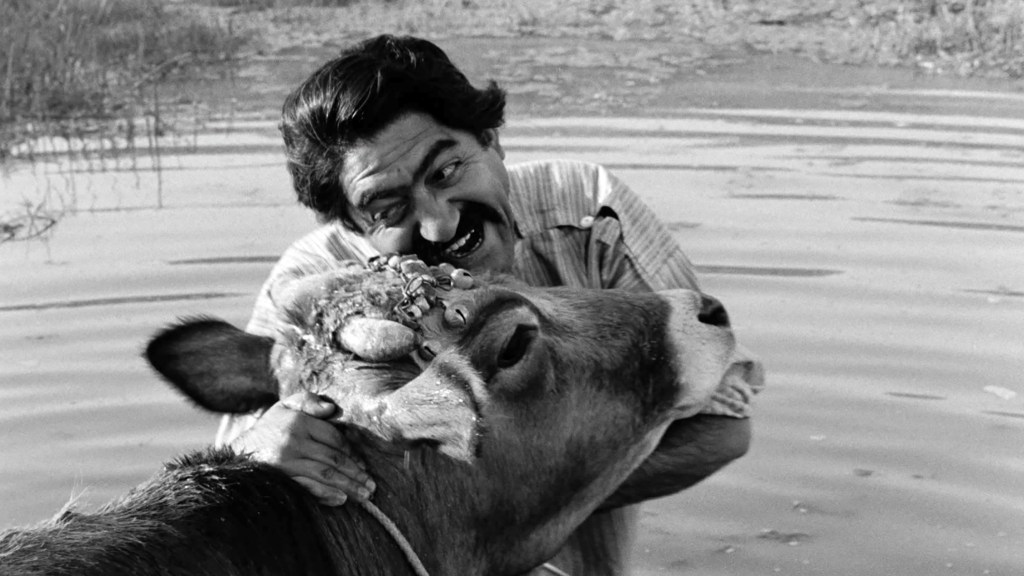

It is important to add that Kiarostami never completely abandoned the documentary style, even during his “poetic” period. He rarely altered natural locations, and in most cases, he simply observed them objectively through the camera, leaving them gently in their original state. The filmmaker never tried to capture an ideal world, and therefore he did not portray nature as untouched by humans. The setting of Taste of Cherry (Ta’m-e gilas, 1997) is a rough quarry, and one of the characters works as a bird preparator at a natural history museum. Rather than seeking pristine nature, the director reveals the power of everyday landscapes inhabited by people.

Variations of the Landscape: Poetic Innovation in Iranian New Wave Cinema

Kiarostami’s poetic contribution lies in his unique way of viewing the everyday Iranian landscape. Besides poetry and documentary style, the way he presents nature is strongly influenced by his extensive experience in photography and his background in painting. The principles of visual art—such as working with perspective, framing, and composition—are so evident that many shots from his films could stand alone as full-fledged photographs. Kiarostami fully developed this approach in his last film, 24 Frames (2017), whose aesthetic approach is based on the concept of living photographs.

The Iranian film director depicts the landscape using two different camerawork techniques. One method places the camera inside a moving car, whose interior often serves as a setting in his films. In this case, the scenery is captured from the limited viewpoints of the traveling characters—through the front or side window glass. The opening scenes of And Life Goes On (Zendegi va digar hich, 1992) and Taste of Cherry take place almost entirely inside vehicles.

This approach allows the audience to follow the dialogue between two characters while simultaneously observing the changing landscape in the background. The division of space into two parts—the car interior and the surrounding scenery—usually does not create isolation but instead develops a connection between the two layers and enhances the viewer’s curiosity to look beyond the characters’ limited viewpoints. For Kiarostami, the car was an ideal personal refuge from which he could quietly and undisturbedly photograph the environment. On the other hand, in The Wind Will Carry Us, the role of the vehicle is different—the dirty windshield makes it hard for the Tehranis to clearly perceive the world outside.

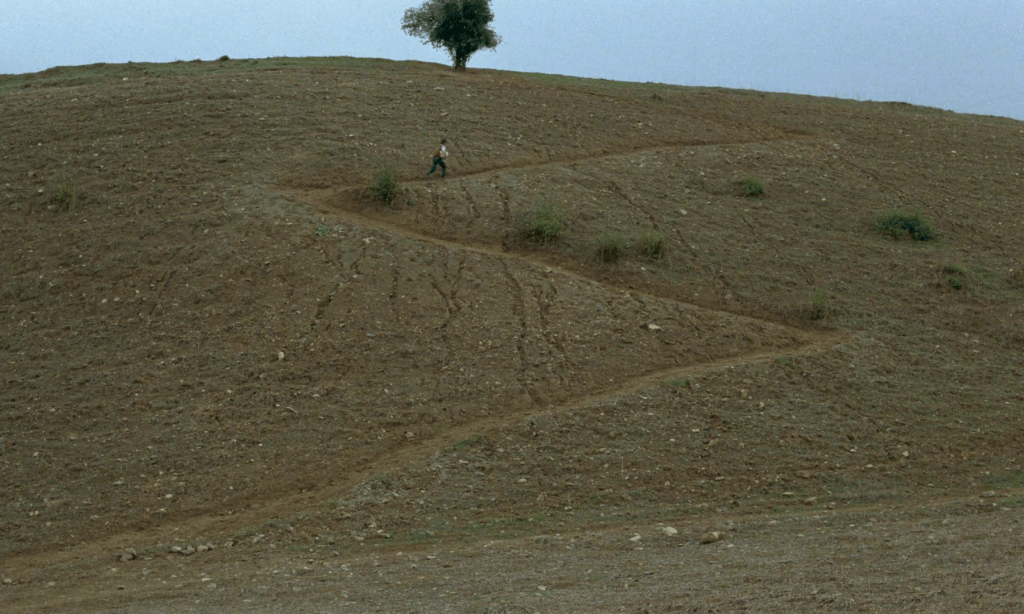

The second, opposite way of filming the landscape involves wide shots that capture the passing car, motorcycle, or a running child on a winding road. The dry plains of Iran allow the director to develop minimalist compositions, where solitary, green trees stand out alongside human elements.

At the beginning of The Wind Will Carry Us, this opposite narrative approach is chosen: the car is shown exclusively in landscape compositions, while the soundtrack delivers the dialogue of the characters inside the vehicle. This technique distances the viewer from the characters and shifts the environment into a dominant position. Some of these observational shots in Kiarostami’s films are accompanied by the voiceover of “old sages” who accompany the protagonists on their journeys. These comments describe the beauties of the world and encourage the viewer to reframe their attention toward the aesthetic value of the landscape.

Besides the photographic impact of the landscape compositions, Kiarostami directs the viewer’s attention to the natural environment through variations of individual motifs and shots. In Where Is the Friend’s House?, a boy repeatedly runs between two villages over a hill. These journeys are filmed each time in series of similar types of shots that capture the landscape between the two villages. The most striking view is of the winding road leading to the summit with a solitary tree. This motif is then quoted in the sequels of the trilogy—And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees (Zire darakhtan-e zeyton, 1994). However, the familiar environment is shot from different angles: in the first case from a car, in the second through the branches of another tree.

Taste of Cherry develops similar variations. In one moving shot, the camera follows a passing Range Rover. When the vehicle temporarily disappears from view due to uneven terrain, the camera autonomously continues moving—across the empty landscape. This shot is varied several times in the film, under different lighting conditions, with different directions of both camera and vehicle movement. Kiarostami creates stylistic variations independent of the narrative’s demands, making the landscape a prominent aesthetic element that is sometimes more captivating than the human protagonists. The repetitions create an analogy to poetic rhyme and give the film a lyrical quality.

The landscape is independent not only of the narrative but also of the film production itself. This is suggested by the metafictional ending of Taste of Cherry, which reveals the film crew and the lead actor, Homayoun Ershadi, during filming. However, the nature we observe in the finale is no longer autumnal—as it had been throughout the story—but springlike. The self-reflective ending allows the viewer to look at the previous story with some distance. At the same time, it points to the autonomy of nature from fiction: the landscape is not frozen unchanging by the film medium, but transforms independently of the filmmakers’ will. This self-sufficiency is only partial—as I have described, the everyday scenery becomes captivating also thanks to the film’s poetic approach.

In the next part, we explore how Kiarostami’s films go beyond mere visual beauty to reveal nature’s deeper, life-affirming power. Discover how his poetic vision invites both characters and viewers to embrace life, weaving together ethics, humanism, and eco-awareness in a unique cinematic experience.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting my blog—whether by making a donation on Buy Me a Coffee or by sharing it with others. Your support helps me keep creating meaningful content. Thank you!

Leave a comment