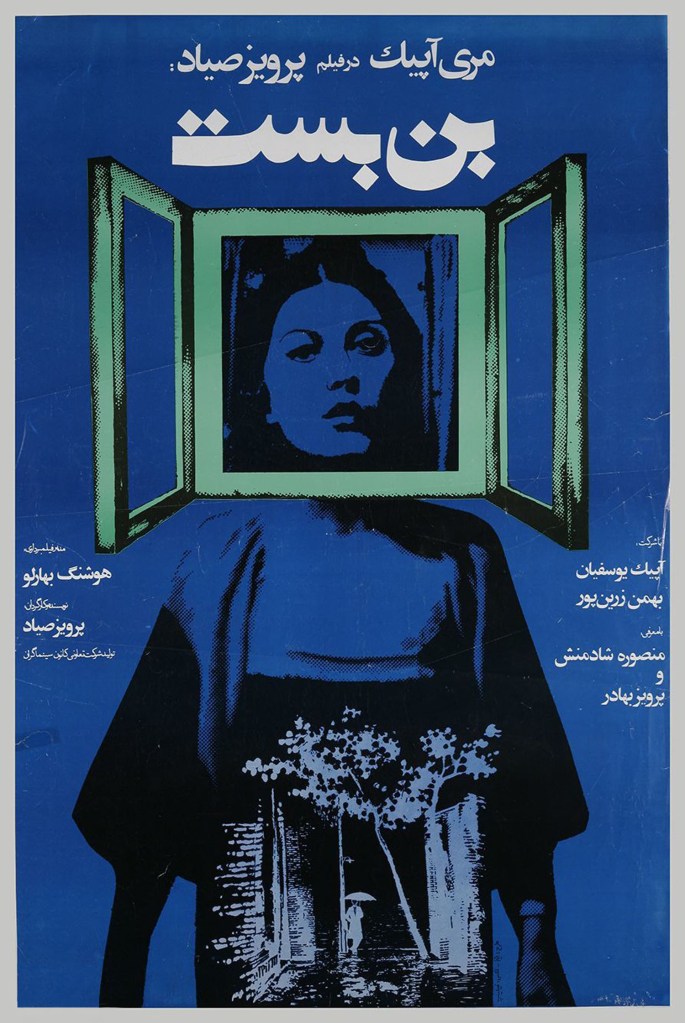

The minimalist film demonstrates Sayyad’s filmmaking talent and his ability to tell realistic stories infused with artistic stylization. The film won the main prize at the Moscow Film Festival for the performance of its lead actress, Mary Apick.

If you haven’t yet seen Dead End (Bonbast, 1977), I recommend watching it first before reading this analysis. Otherwise, the spoilers below may weaken the intensity of your viewing experience.

Sayyad began as a playwright, initially publishing his plays in a theater magazine. When Iran’s new theater movement was emerging and looking for fresh talent, he entered the world of stage performance. Sayyad rose to fame with the character Samad, a comic figure. Although Samad appears at first glance to be a simpleton, he is actually a clever rural man with a childlike soul, struggling to come to terms with the hypocrisy around him. Samad appeared in a popular series of films in the 1970s and became an iconic comedic figure of pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema.

Sayyad used the profits from the popular Samad films to finance non-commercial New Wave films. He produced films for directors who otherwise would have struggled to find support. Among others, he produced Ebrahim Golestan’s The Secrets of the Treasure of the Jinn Valley (1974) and Sohrab Shahid Saless’s Still Life (1974) and Far From Home (1975), in which he also played the lead role.

He approached the production of art films with deep respect for individual filmmakers. Sayyad said: “For me, producing these films was also a form of personal fulfillment… When Golestan’s film was completed, I was overjoyed, because it meant one more film of exceptional value had been added to the collection.”1

Sayyad’s directorial work Dead End is a New Wave-style film based on a short story by Anton Chekhov. It is a melodrama with political undertones that was banned shortly after its release. The film was created under the auspices of the Progressive Filmmakers’ Cooperative (Kanun-e Sinemagaran-e Pishro), an independent collective supporting the new cinema movement.

The film tells the story of a young girl (Mary Apick) living with her mother in a small house at the end of a dead-end alley in Tehran. She falls in love with a handsome and mysterious man (Parviz Bahador) who lingers in the alley, silently watching her through her bedroom window. At the end of the film, both the protagonist and the audience are confronted with a shocking revelation: the man is actually a SAVAK agent waiting for the right moment to arrest her brother (Bahman Zarrinpour) for his political activism against the Shah. Unaware of his true identity, the girl believes he is in love with her. His voyeuristic gaze stirs both passion and disturbing anxiety in her.

In the Shadow of Surveillance

To better understand the atmosphere of the time in which Dead End was made, we must first look at the roots of societal tension in 1970s Iran. This tension traces back to 1953, when a CIA- and MI6-backed coup overthrew the democratically elected, secular-leaning Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. Mosaddegh, together with the parliament and with strong public support, nationalized the Iranian oil industry, which until then had been controlled by the United Kingdom.

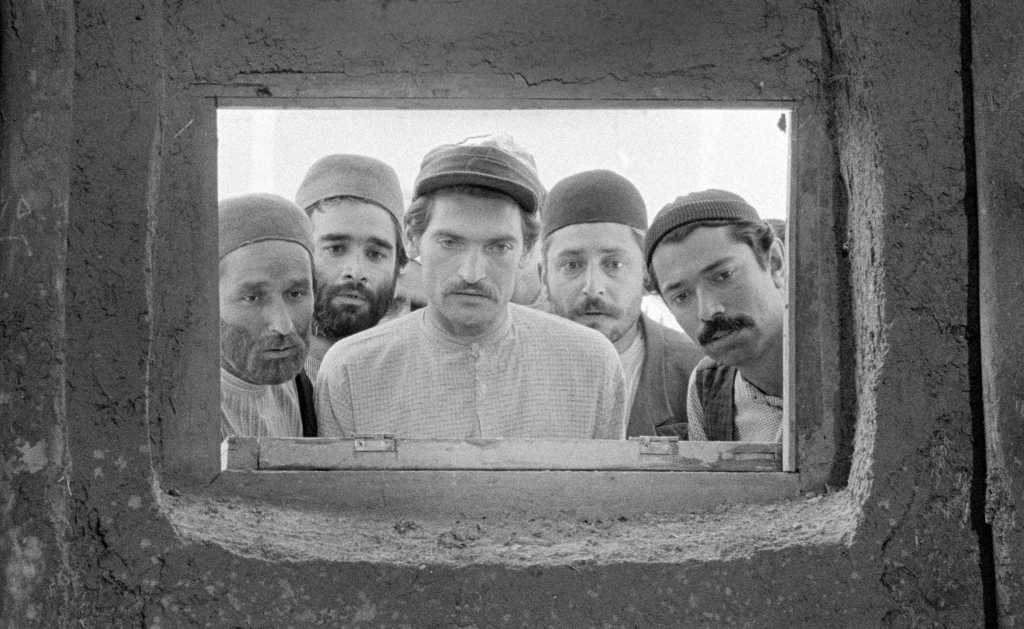

Before the coup, Iran was a constitutional monarchy—although the Shah held significant power, it was limited by an elected parliament. After the coup, this balance was overturned. The Western-backed intervention allowed Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to gain absolute power, which he increasingly embraced. With strong support from the CIA and Israel’s Mossad, he founded the SAVAK—a centralized secret police force that monitored opposition and suppressed dissent. Intellectuals, artists, and ordinary people resisted the autocratic regime, as illustrated by the example of the protagonist’s brother in Dead End.

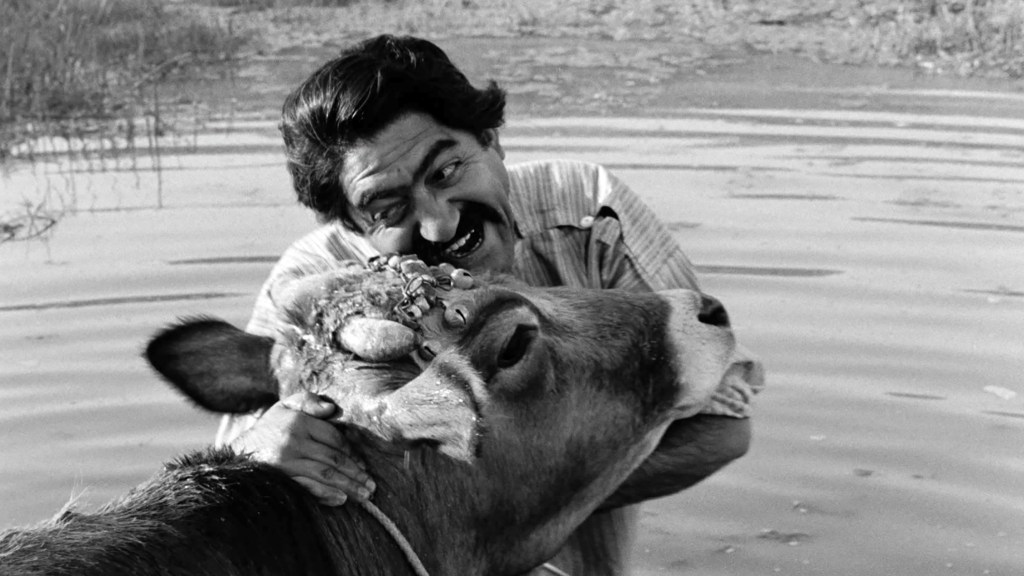

Set in a confined space, Dead End portrays Iranian society under the Shah as a claustrophobic prison—a panopticon in which citizens are constantly under surveillance. As in The Cow (directed by Dariush Mehrjui), fear is omnipresent—not of mysterious villagers, but of the relentless gaze of SAVAK agents. Iranian cinema historian Hamid Naficy writes of the film:

“The title refers not only to the alley in which the heroine lives but also to the dead-end lives of women and others—at least politically—in the last years of the Pahlavi period. The film sees no way out of the hermetic panopticon, no way to resist or to rebel, for those who dare to do so, like the brother, pay dearly.”2

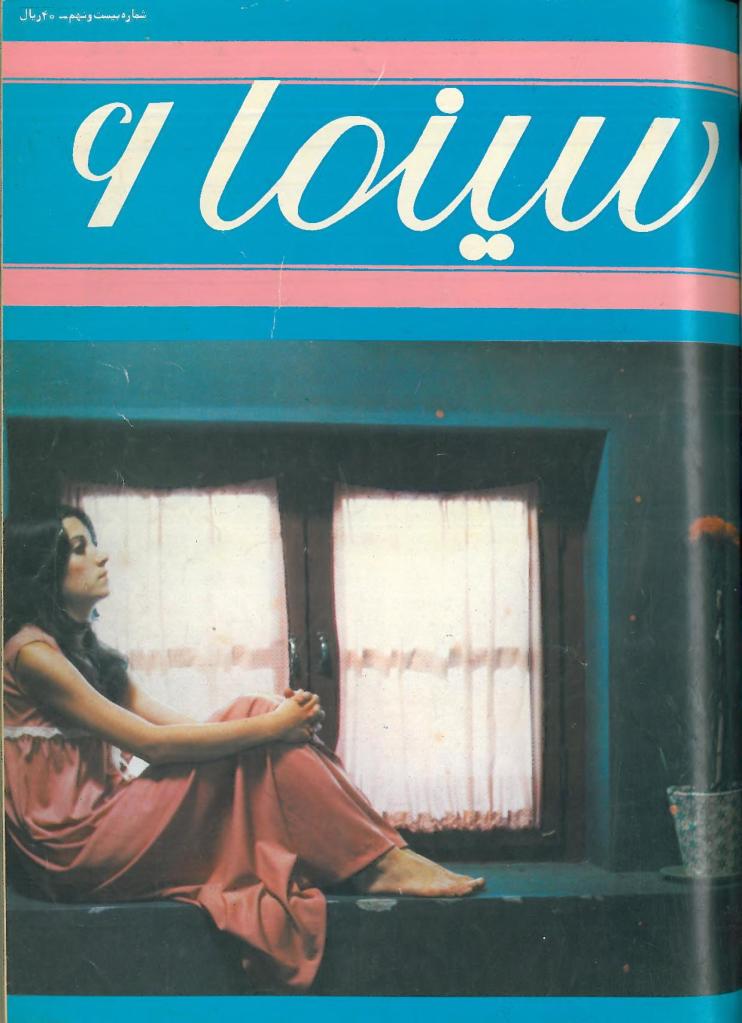

In Dead End, fear is portrayed with deep psychological complexity. The main character is perpetually anxious, insecure about her appearance, and dissatisfied with her face. She uses bold red lipstick and wears attractive red clothing in an attempt to mask her insecurity and provoke a response from the stranger. Beneath all these facades, fear remains vividly present in her eyes. Her anxiety sharply contrasts with her friend Souri (Mansooreh Shadmanesh), who acts provocatively and seems carefree and experienced.

Between Realism and Stylization

The concept of realism is often associated with the Iranian art cinema. Dead End is clearly grounded in this realist aesthetic but also subverts it with elements of artistic stylization. The film is a distinctly modernist work that combines objective realism with subjective techniques, sometimes bordering on the surreal. The sounds of morning rain or evening cicadas create an eerie yet mysterious atmosphere. The dialogue is intentionally theatrical and literary, disrupting the film’s realist tone.

One striking device is the use of a flashback sequence. A black-and-white flashback appears suddenly during a conversation between mother and daughter at the dinner table. This scene links the mother’s monologue with the sounds of a crowd at a wedding celebration depicted in the flashback. The technique emphasizes the contrast between objective realism (the ongoing conversation in the present) and the heroine’s mental subjectivity (memories of the past).

The girl’s room reflects both the socio-cultural context and her inner psychological state. The gray walls of her confined space resemble a prison cell, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere. The room combines Western cultural motifs with traditional Iranian elements, reflecting the tension between tradition and modernity characteristic of that era. In contrast, Souri’s room contains no traditional elements; it resembles a typical middle-class girl’s room—brighter, more spacious, and free of claustrophobia.

The use of color and décor is also symbolic. The main character, with her pale face, resembles the figure in the Persian miniature that hangs on her bedroom wall. At first, she dresses in provocative red, symbolizing passion and desire. But when the mysterious man suddenly stops appearing in the alley, leaving it empty, she falls into despair, convinced she has lost his interest. She then dresses in black and stops using lipstick. Red and black thus become powerful visual motifs throughout the film, appearing not only in costumes but also on the girl’s umbrella and in the café where characters meet.

The protagonist’s fear of the mysterious man, who simultaneously evokes desire and curiosity, can be interpreted through a psychoanalytic lens. Sigmund Freud emphasized the ambivalence between Eros (the life drive—love, sexuality) and Thanatos (the death drive—anxiety, destruction). According to Freud, desire and fear are not opposites but are deeply intertwined. Jacques Lacan’s theory of voyeurism furthers this idea: the moment the girl realizes she is being watched, she enters into a relationship in which she is defined by the gaze of the other. This gaze can be disturbing, but also exciting, as it affirms her existence as a “desirable object” in the observer’s eyes.

From Parody to Modern Tragedy: A Film Adaptation

Among other qualities, Dead End stands out as a brilliant adaptation. It is based on Anton Chekhov’s 1883 short story From the Diary of a Young Girl (1883). The story is told entirely from the girl’s point of view, in the form of a diary describing several days of her life. It is a typical Chekhovian grotesque, revealing how easily people build illusions and how difficult it is to face the truth. The basic plot, originally set in Tsarist Russia, remains the same: a girl sees a mysterious and attractive man through her window and convinces herself he is in love with her.

The diary format of Chekhov’s story explains Sayyad’s strong use of subjective monologues in the film. These monologues are marked by literalness, pathos, and irony—much like the original story, which satirizes feminine pride. In the short story, the protagonist’s self-centeredness is caricatured and comical. Sayyad’s film, however, is more complex. It transcends irony and imbues the narrative with poetic beauty. The heroine expresses her thoughts aloud: “Who are you? What are you? My love? My man? My fate?”—and unlike the story, these words do not feel laughable, but rather compose a deeply poetic monologue of a tragically in-love woman.

This contrast between story and film is most striking in the endings of each. Chekhov’s story ends humorously. When the girl discovers the man was actually tracking her brother Seriozha, who had embezzled money, she angrily writes in her diary: “Bastard! Disgusting! Turned out he was tracking my brother Seriozha the whole twelve days. Bastard… I stuck my tongue out at him.”3 This abrupt shift from self-confidence to wounded pride is ironic. The story parodies romantic diaries—its heroine misreads everything, seeing the world as a melodrama with herself at the center. In reality, she is entirely irrelevant.

Unlike the story, Sayyad’s film evokes a powerful sense of tragedy, enriched and intensified by poetry. As the protagonist awakens to the truth and sees the man leading her brother away in handcuffs, a melancholic poem by Ahmad Shamlou is heard. The poem expresses disillusionment, despair, and the deep inner tension arising from a desire for love as safety—but instead, there is only confusion, coldness, and pain. Shamlou reflects on the dissonance between the ideal of love and its actual form: love is not comfort, not passion, not beauty. It is a modern, existential view of love—not a romantic salvation, but something that often wounds and disappoints. In this sense, Sayyad’s Dead End offers a tragic perspective on the decline of tradition and the rise of modernity in Iranian society.

Writing this article took a lot of effort, as I worked, among other things, with sources in Persian, English, and Russian. If you found it meaningful, a coffee would mean a lot—I truly appreciate your support.

- “Darbare-ye Parviz Sayyad – sazande-ye film-e Bonbast.” Sinama – Jashnvare-ye Jahani-ye Film-e Tehran 6, no. 5 (November 20, 1977). ↩︎

- Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 362–363. ↩︎

- https://ru.wikisource.org/wiki/Из_дневника_одной_девицы_(Чехов) ↩︎

Leave a comment